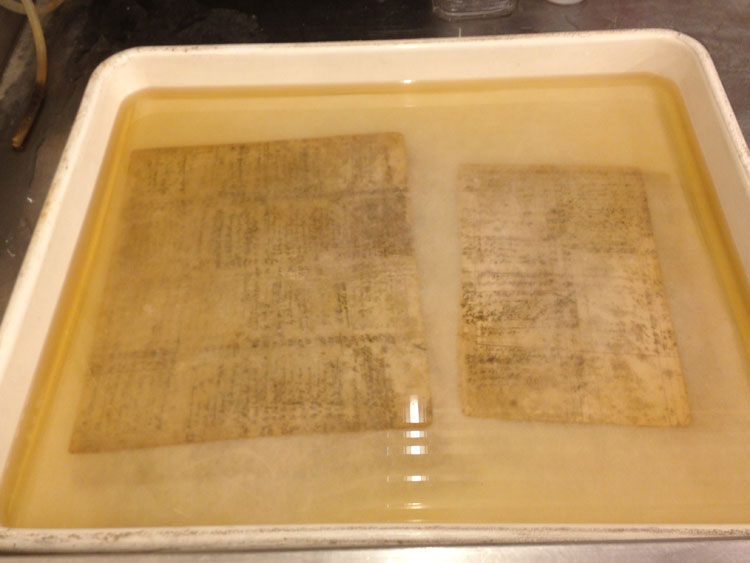

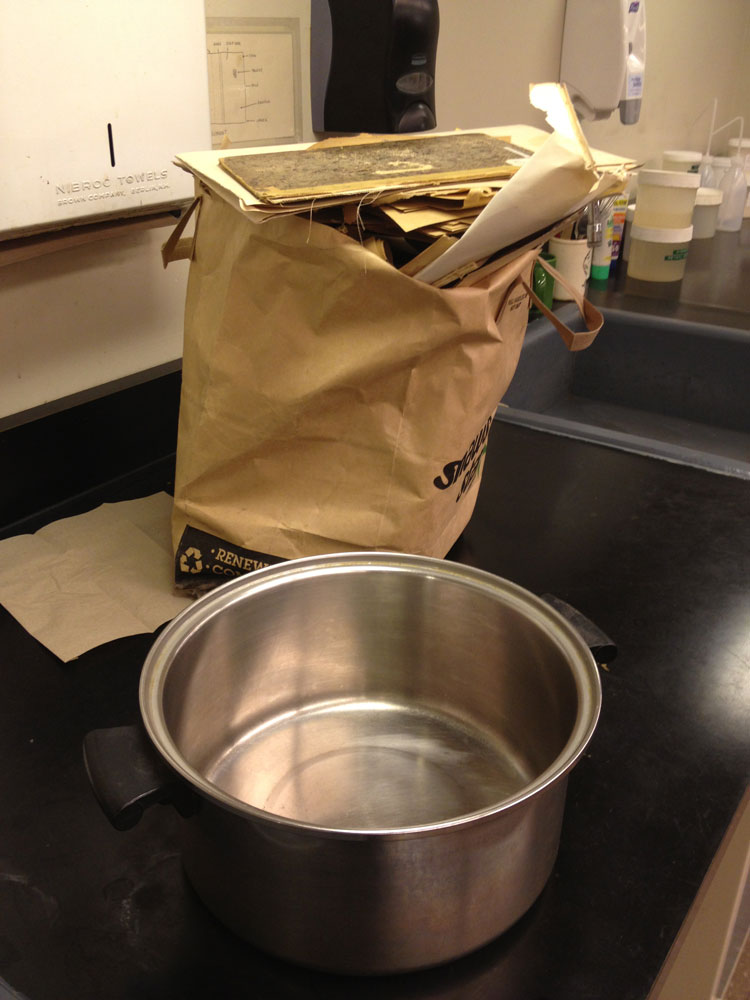

Earlier this year, as part of the Conservation Conversations column, Lauren Schott wrote an article on su-su, which highlighted the steps to creating this alternative matter for toning materials as part of the conservation treatment. Also referred to as paper dirt or paper extract, I was first introduced to this alternative toning pigment at North Bennet Street School by my instructor Martha Kearsley. Later on, I used it while interning at the Boston Public Library, just as Lauren did the following year during her internship.

Conservation is a science and therefore it evolves as our understanding of it grows through research, experiments, discussions and time. John O’Regan recently brought the following article to my attention, which he found through CoOL (Conservation OnLine). In 2008, Erin Gordon of Queen’s University wrote Comparing Paper Extract to Traditional Toning Materials. Erin’s introduction to paper extract came during a workshop conducted by Renate Mesmer, Head of Conservation at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C. The information Renate presented was largely based on an article by Piers Townshend, Head of Paper Conservation at the Tate Conservation Department. Interestingly, this is the same article Lauren cites in her post as further reading on the subject.

Erin’s paper, as the title suggests, is based on her research conducted for the purpose of her studies in the Master of Art Conservation program at Queen’s University. If you are interested in knowing the science behind paper extract and other toning materials, I suggest you read through Erin’s paper. But those of you who are interested in reading the exciting conclusions Erin found right now, well here it is:

So the point of this post, is not to claim that Lauren or anyone using su-su is wrong in their methods (because it might be the most appropriate). But that as professions in the field of conservation, there is a responsibility to understand the positive and negative consequences of the treatments and materials employed (and how those factors may change over time). The pros and cons must be weighed for each object individually, while keeping in consideration its history, its function and its future. Understanding our materials and why we choose to bind, rebind or repair a book in a certain way must continually be reaccessed.

I’ve targeted the conservator throughout this post, but I don’t believe that professional bookbinders are free of this task either. As is the case with most professions, we grow as an industry and individual through consistent research, experimentation and discussion.