1. Recently installed at the Shatin Park in Hong Kong is Kaleidome, a structure for children to play on. But the real beauty lies in its design. The brightly colored, stainless-steel dome is angled in a way that alters your perception of the surrounding city; just like viewing the world through a kaleidoscope.

2. Chris Wood labels himself as a ‘glass and light artist’. Using dichroic glass (two color optical coating that selectively reflects certain wavelengths of light) Chris creates these glowing wall pieces that reflect light in the most intriguing way.

3. The candy colored palette of Barbara Dziadosz‘s illustrations are deliciously eye catching. Barbara is a Polish freelance artist specializing in character design through illustration and printmaking.

4. Enjoy these dreamy paintings from artist Jenny Prinn.

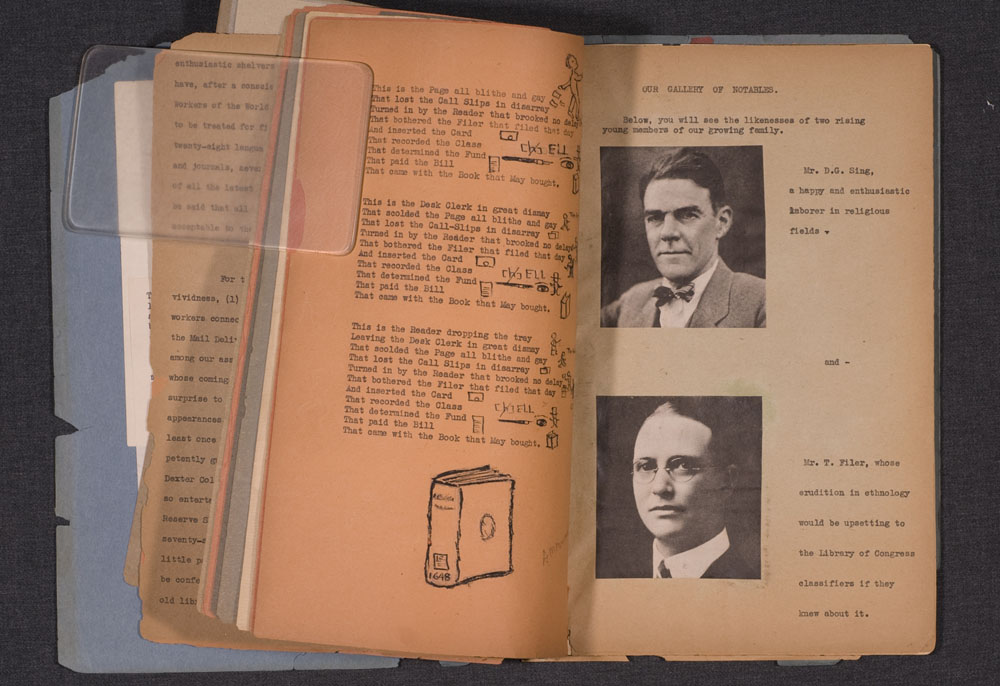

5. The scope of Henry Darger’s work is wildly impressive and incredibly strange. A new exhibition of his work is on view at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris. You can read more about Darger here or treat yourself to the documentary In the Realms of the Unreal.

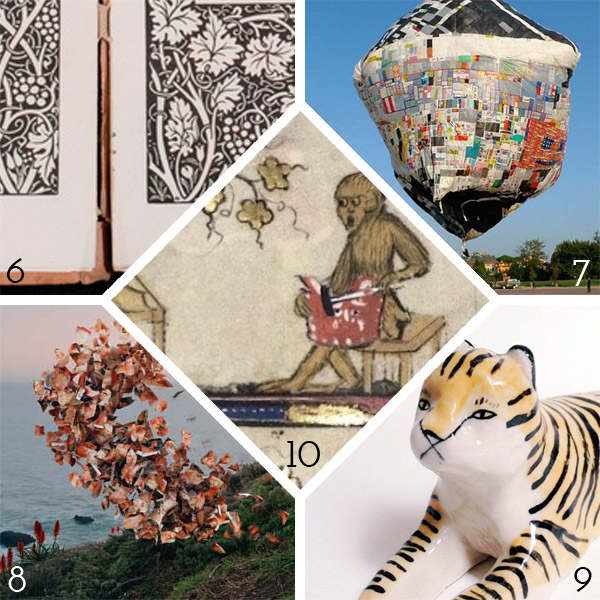

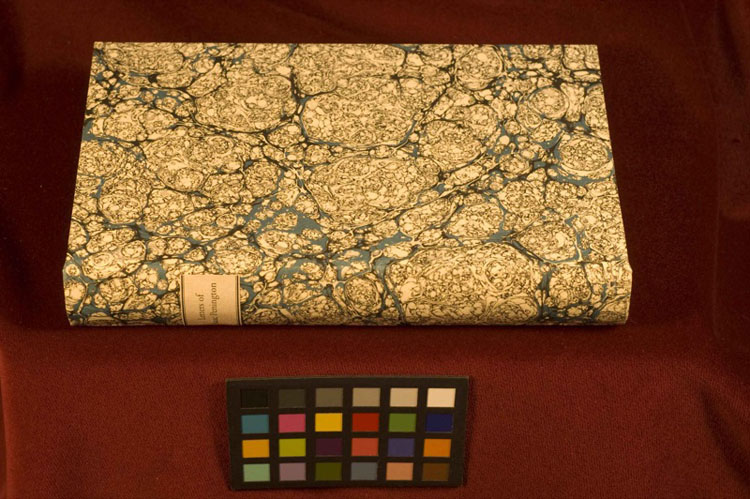

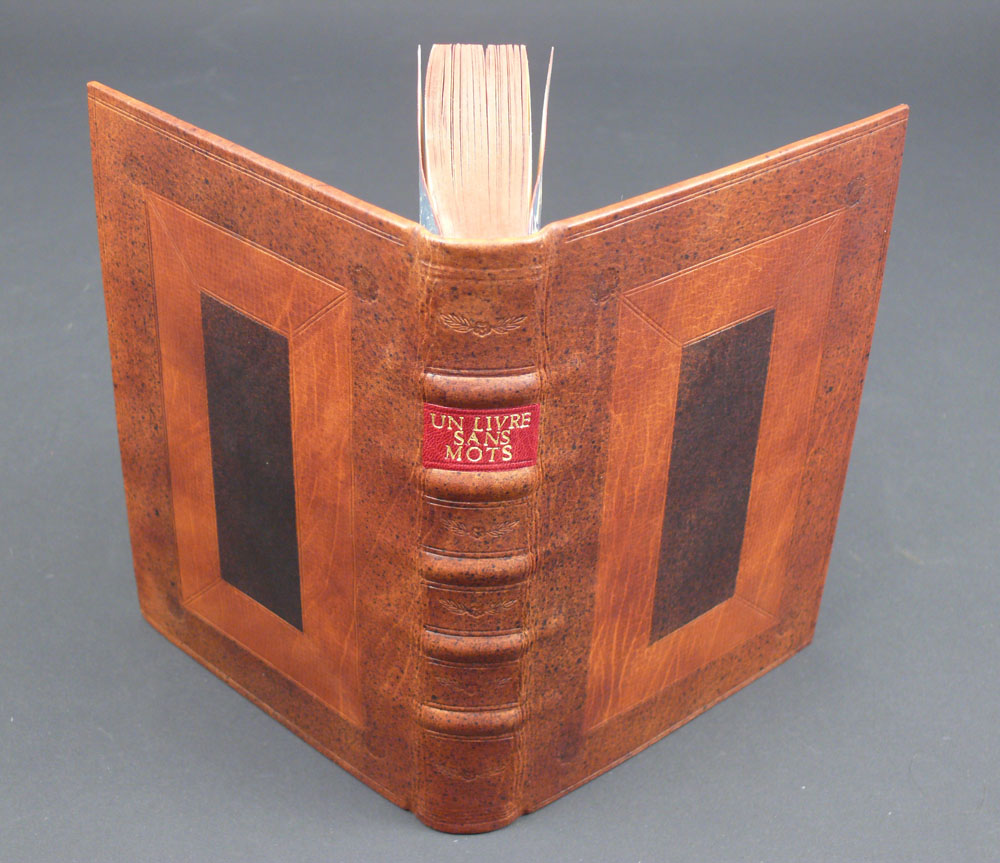

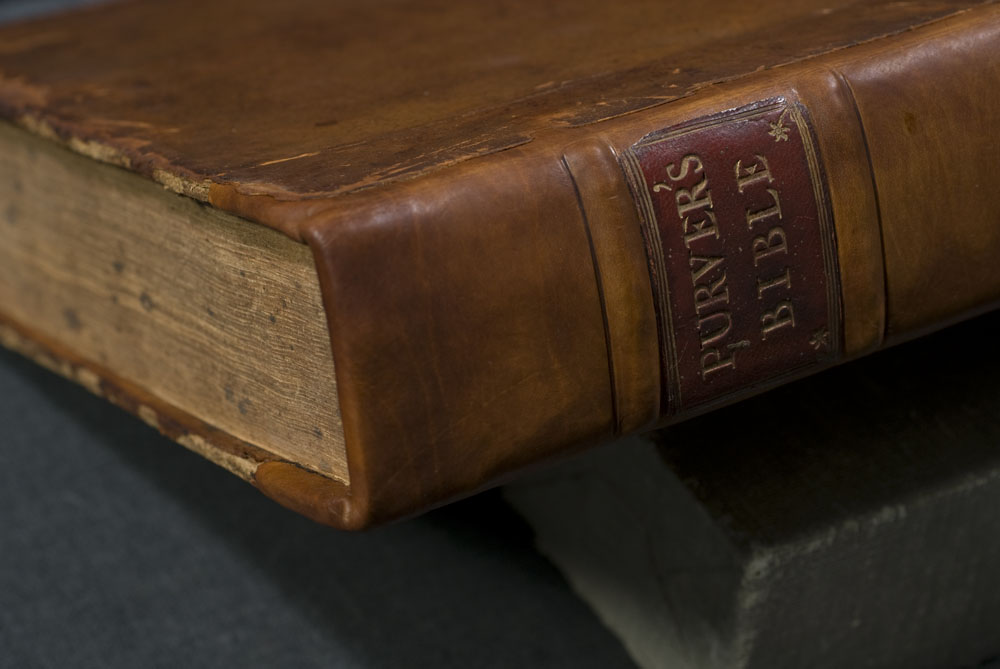

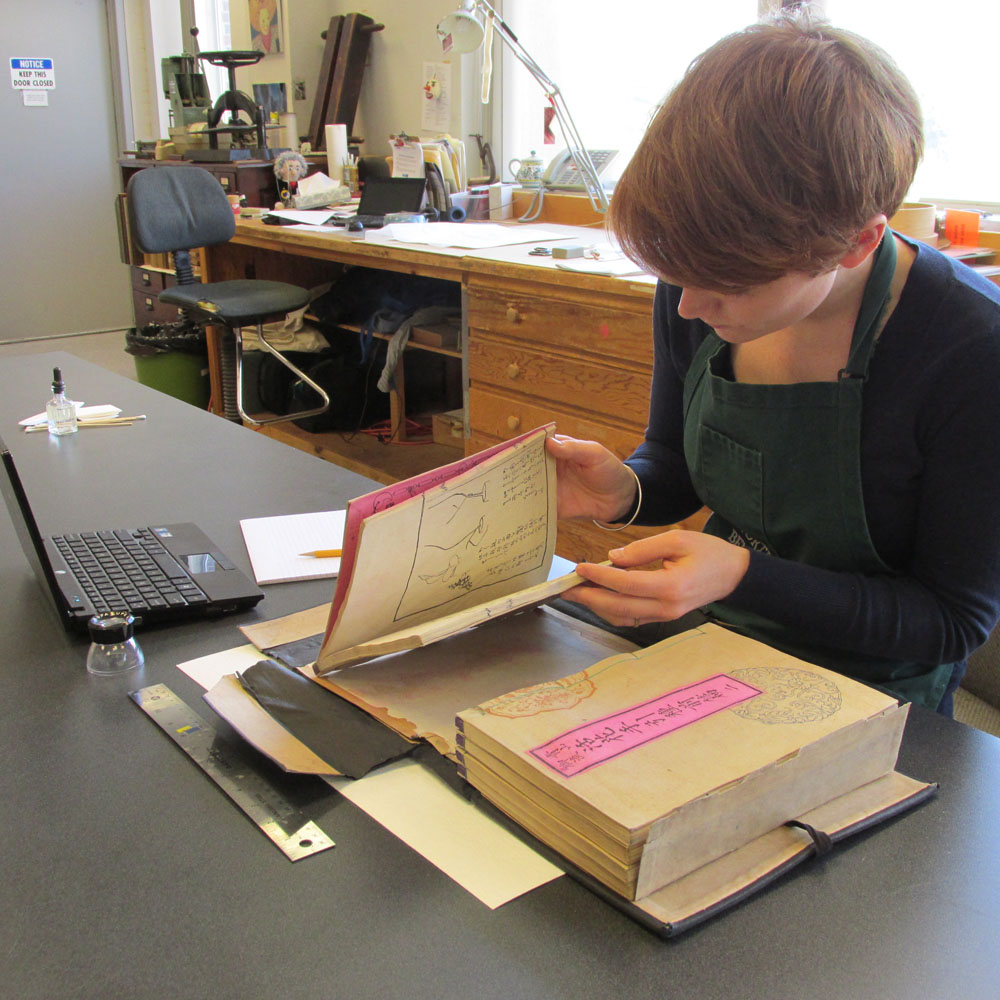

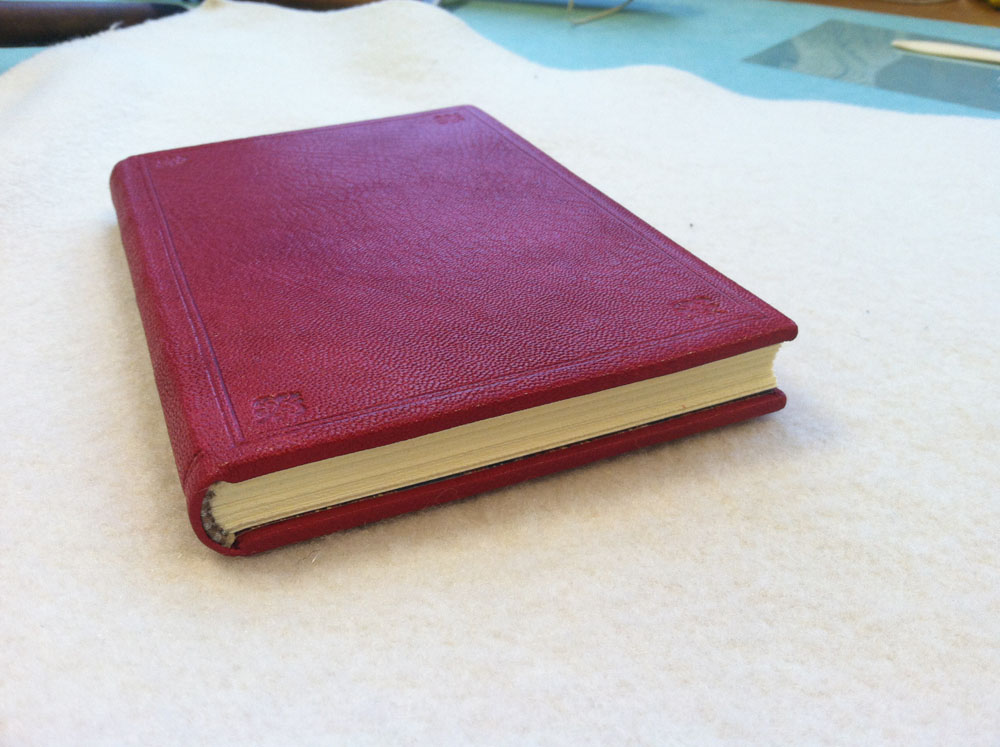

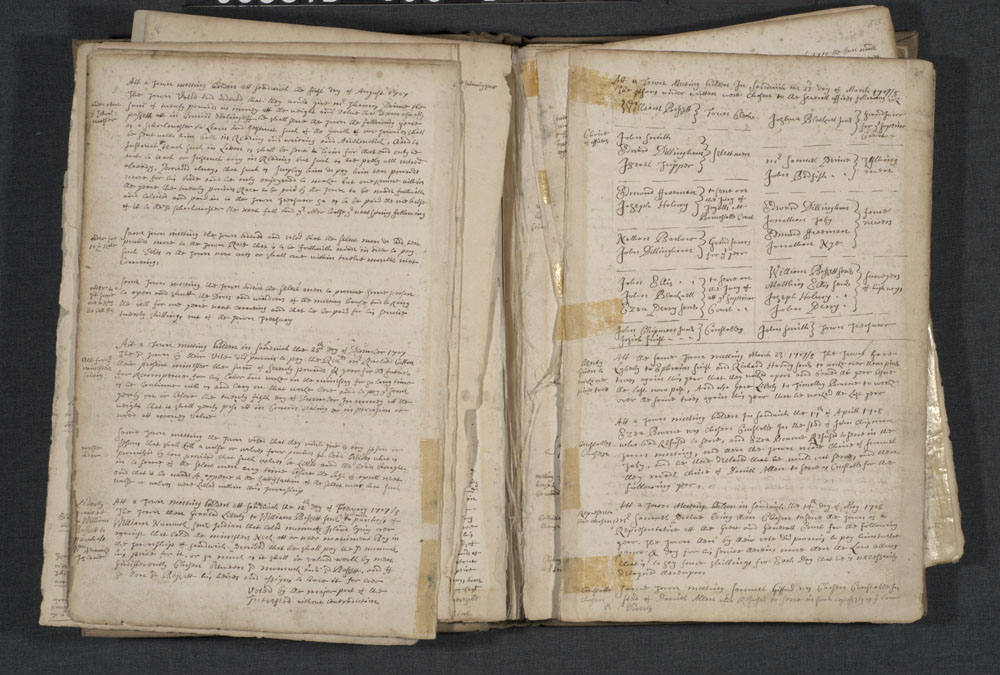

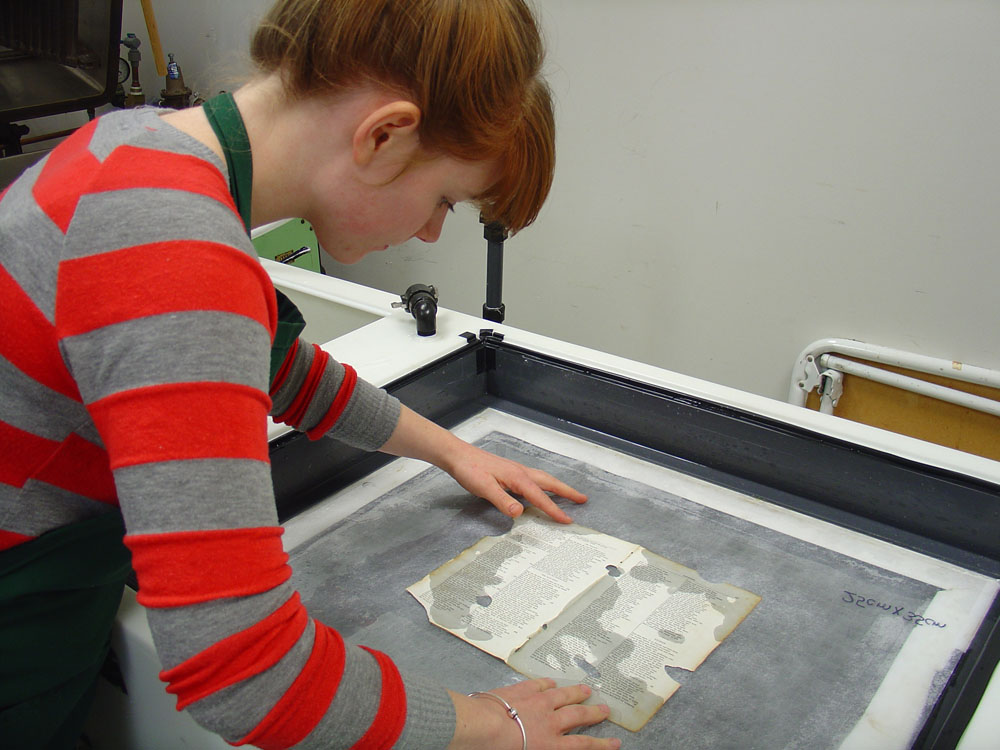

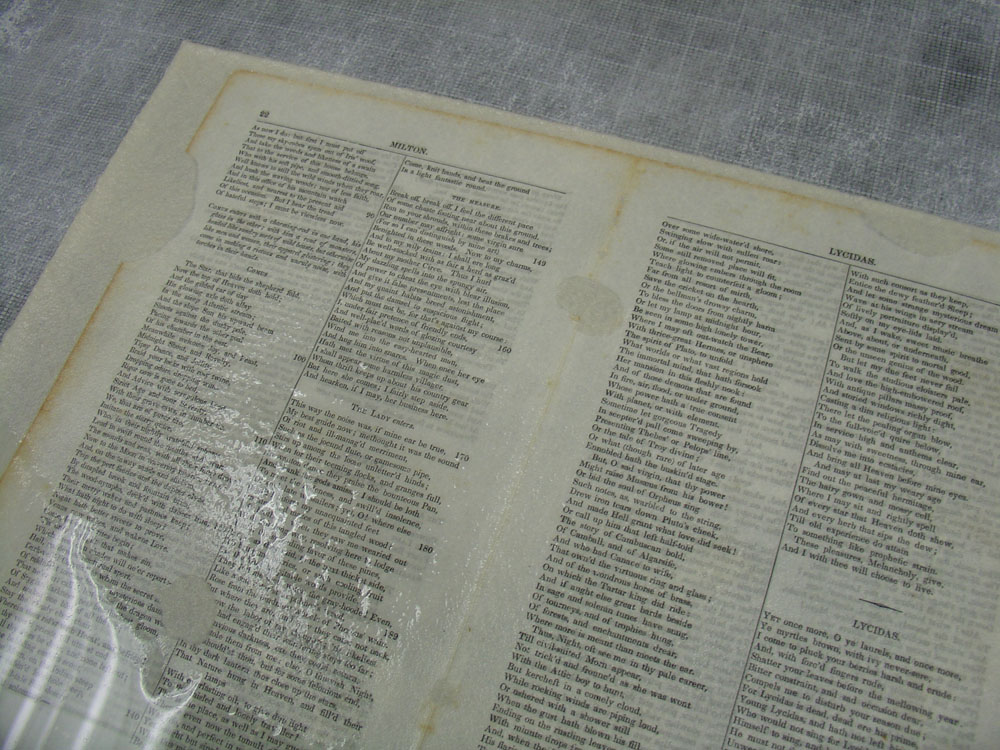

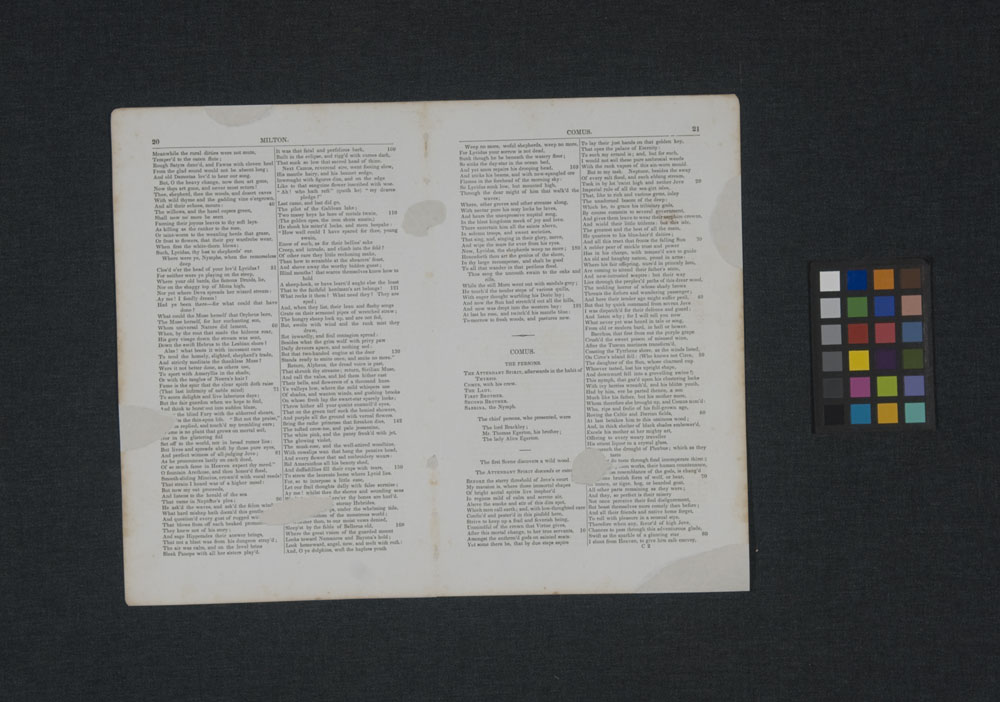

6. The Northeast Document Conservation Center (NEDCC) recently completed a repair job on an original binding of William Morris’ The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer published in 1896. You can read about their treatment here and why it was so important to preserve this historical binding.

7. Tomás Saraceno has constructed a massive hot air balloon in response to our environmental impact. Tomás interprets the hot air balloon as a symbol of escapism from earthly troubles; Becoming Aerosolar is a body of work that speaks about the magnitude of human consumption and waste.

8. Emergent Behavior is a whimsical photographic series from Thomas Jackson. Ordinary objects erupt in chaotic storms amongst beautiful landscapes. Thomas experiments with tutus, cups, streamers, marshmallows and more.

9. I love the illustrations from artist Jen Collins, but her ceramic works just delight me. You can see all of her available pieces here at Bolden Ceramics.

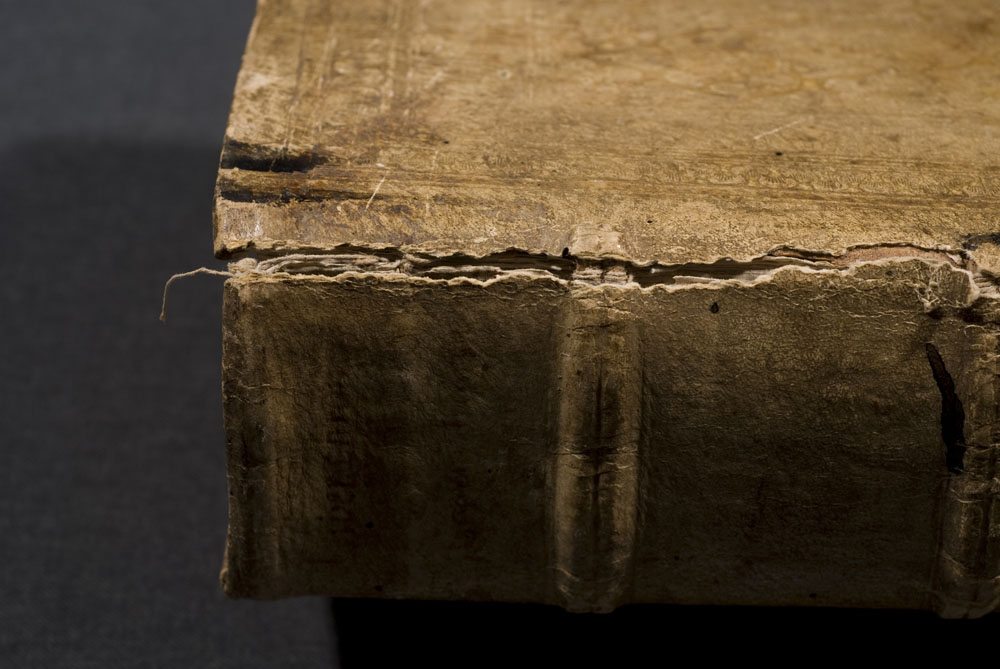

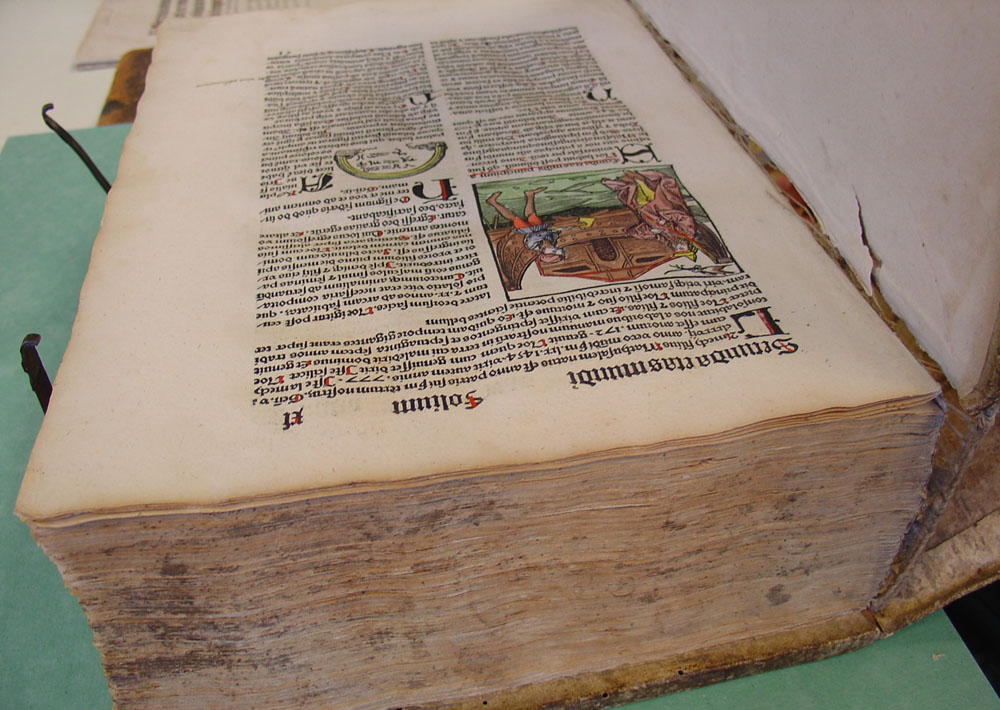

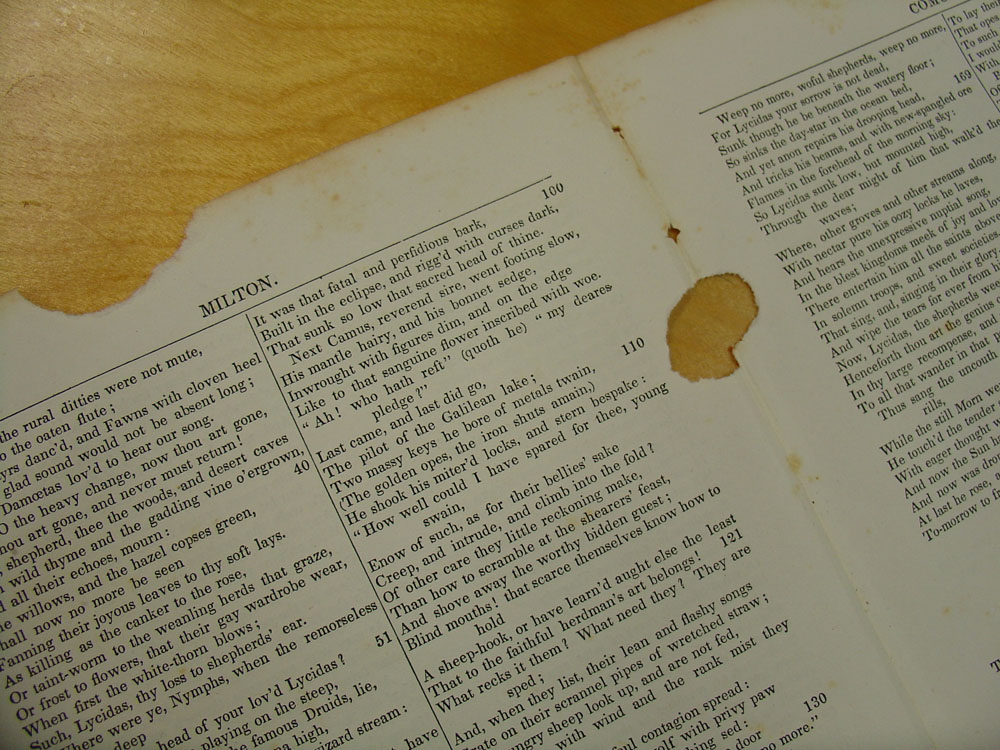

10. Check out this comprehensive article regarding the history of vellum and parchment, which highlights historical production and uses.