Wow, this has been a busy, busy year and I can’t believe that 2015 is coming to end. I want to extend my gratitude to the people who have helped contribute to the blog this year:

– Kathy Abbott

– Ben Elbel

– Tini Miura

– Tracey Rowledge

– Natalie Stopka

– Marianna Brotherton

– Henry Hébert

– Becky Koch

– Athena Moore

– Jacqueline Scott

I also want to thank everyone who reads the blog, subscribes to the blog and newsletter and to those who’ve left comments. It has really warmed my heart to see the growth of interest and recognition that the blog has receive over the course of the year.

At this time I like to reflect on my year. Herringbone Bindery saw a nice shift in workflow this year. As I removed conservation and repair services, I saw more edition work come my way. A few of these projects will be finishing up early in the new year and I plan to write up a post about them. I had another successful year teaching at North Bennet Street School with roughly 85% of my offered workshops running. I also began my second year as a Middle School Book Arts instructor. It’s been so delightful to see the creativity flow from the kids, stay tuned for a new feature on the blog.

What to expect in the New Year:

– an updated website: My husband and webmaster has been working on a beautiful new and easy to navigate website. We hope to have it up and running before the end of March.

– I’ll be working on a fair amount of design bindings in 2016 and will be posting about them along the way

– another round of interviews

As I do every year, here is my list of favorite posts from 2015.

1. December // Bookbinder of the Month: Kathy Abbott

I am really delighted by this interview with Kathy Abbott. She is very methodical about her approach to design binding from selecting the perfect goatskin to applying her decorative techniques. Kathy’s discipline is inspiring and so are her simplistic designs.

2. Artist: Rachel Foullon

3. Client Work // Ye Sette of Odd Volumes

4. Makin’ Care of Business Interview

In July, I was interviewed by Rachel Binx at Makin’ Care of Business. It was a great way to reflect on my successes and how I’ve overcome challenges throughout the years I’ve been in business. I was honored to be apart of this collection of interviews with other talented craftsman and artisans working successfully as entrepreneurs.

5. Artist: Nicholas Schutzenhofer

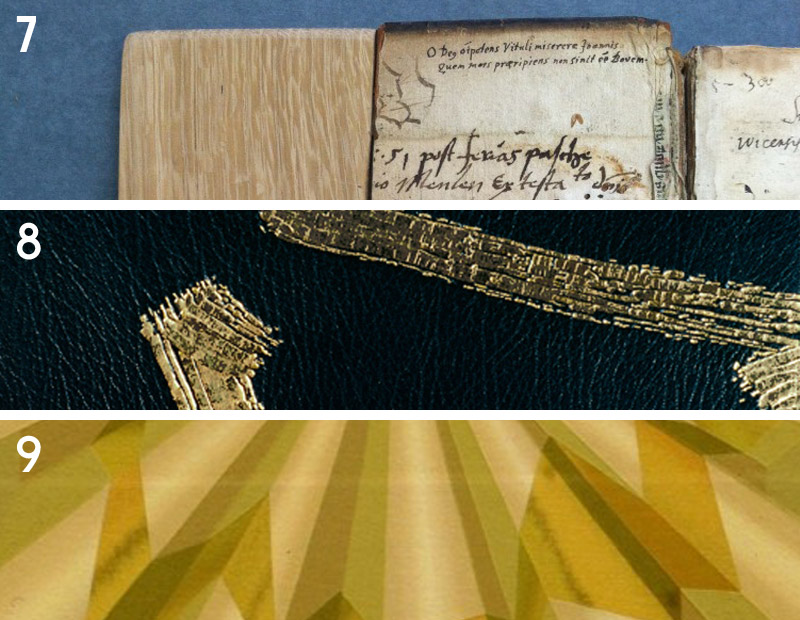

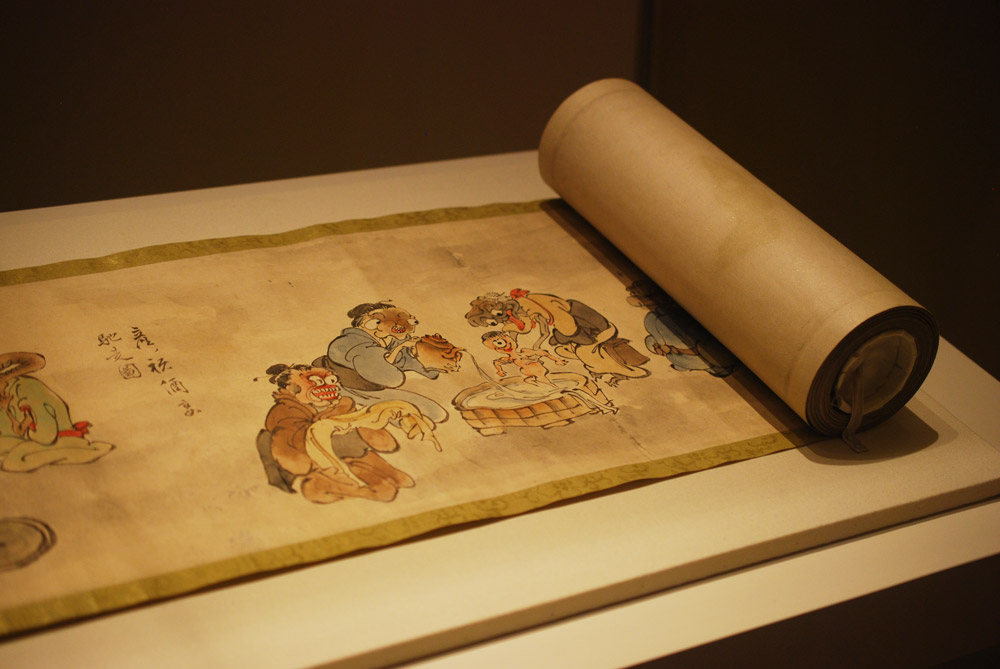

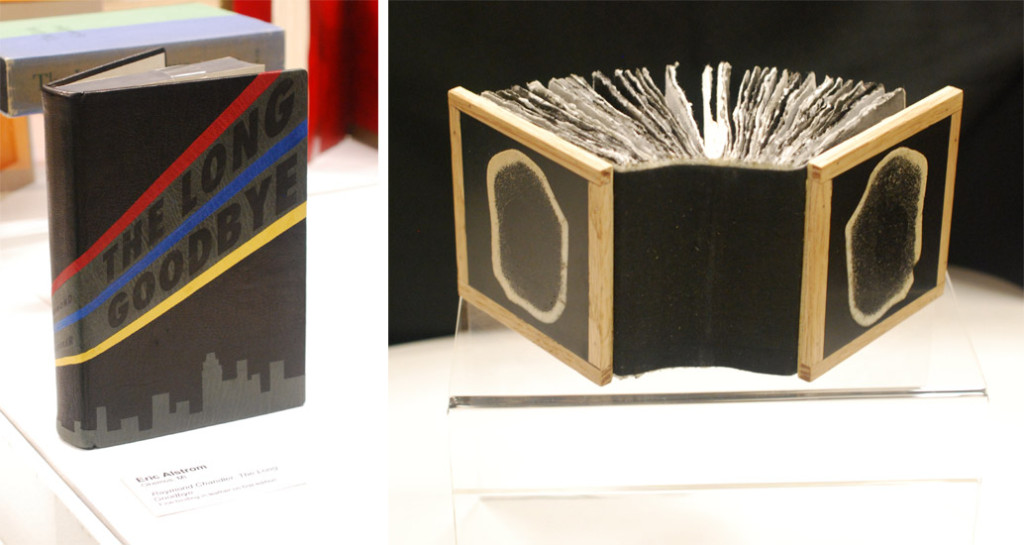

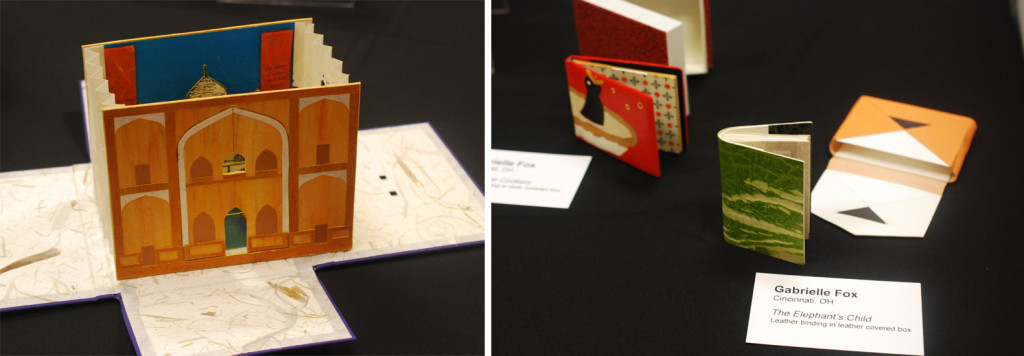

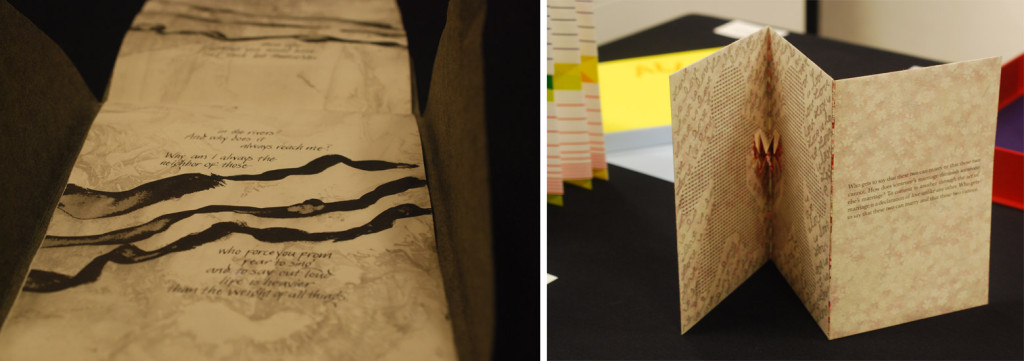

6. North Bennet Street School // Student and Alumni Exhibit 2015 – Part One & Part Two

I love writing this post every year. It’s a joy to speak with the students about their design bindings; detailing their concepts and techniques, what worked and what didn’t. This year’s exhibit also included a lovely selection of bindings from alumni, which you can read about in Part Two.

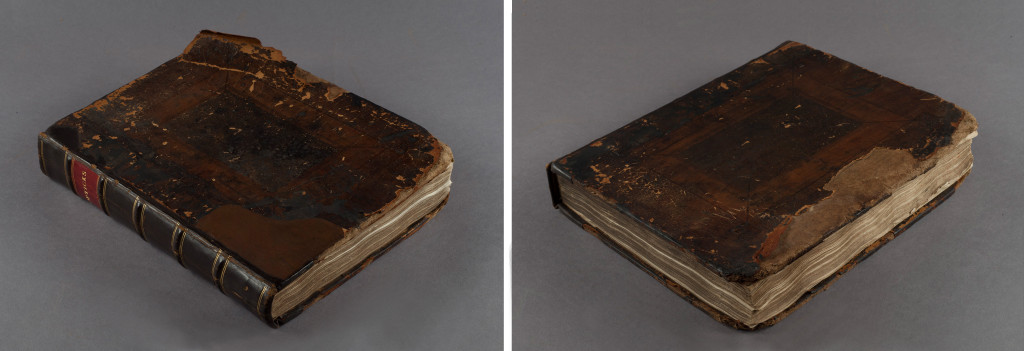

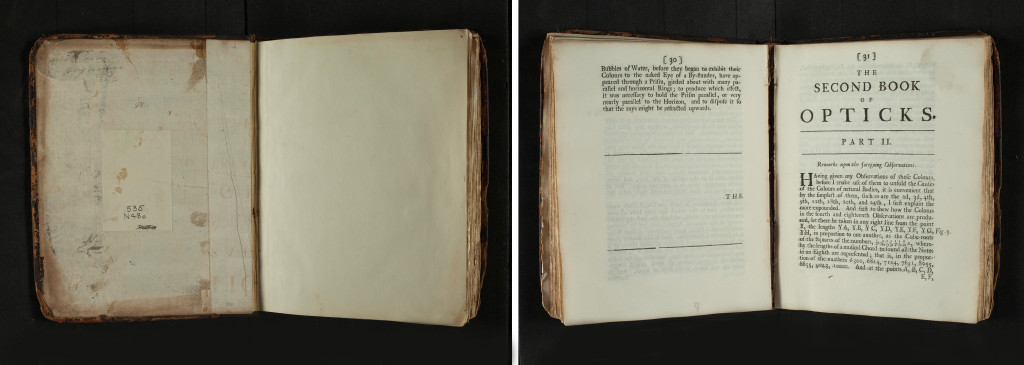

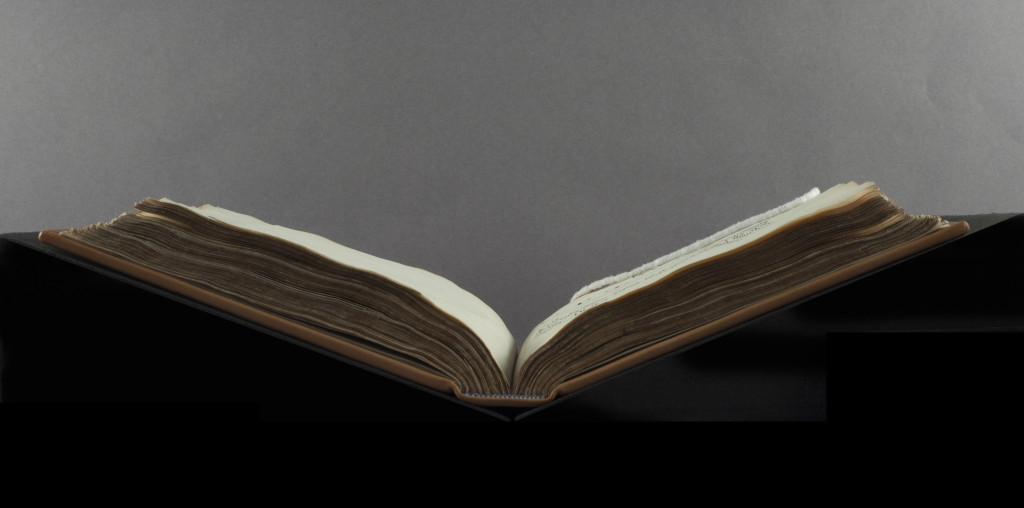

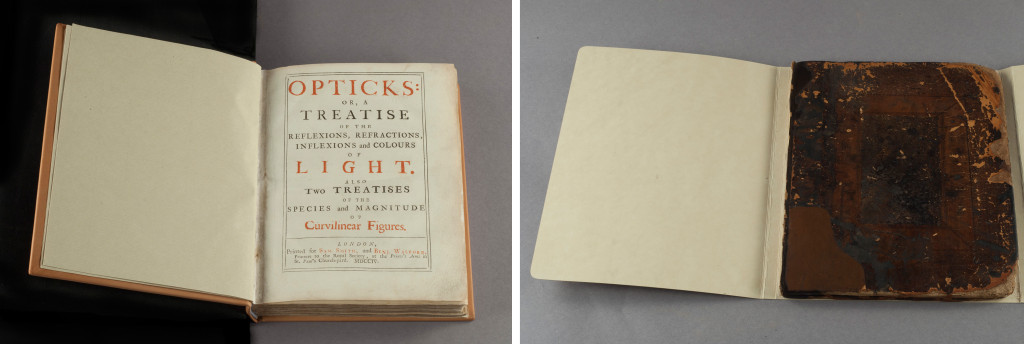

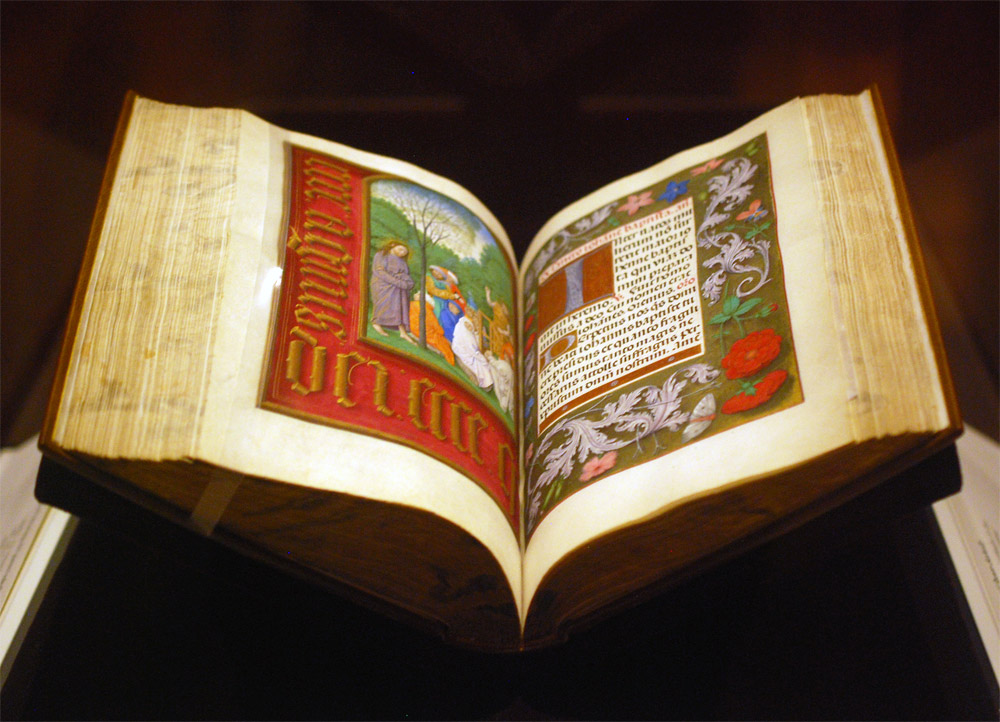

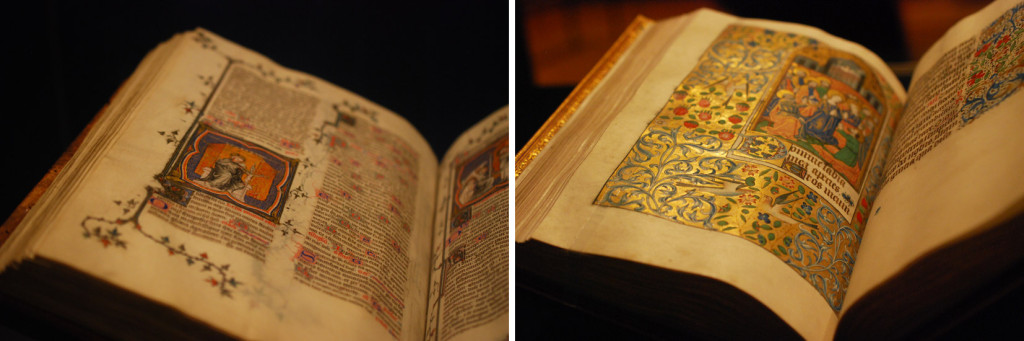

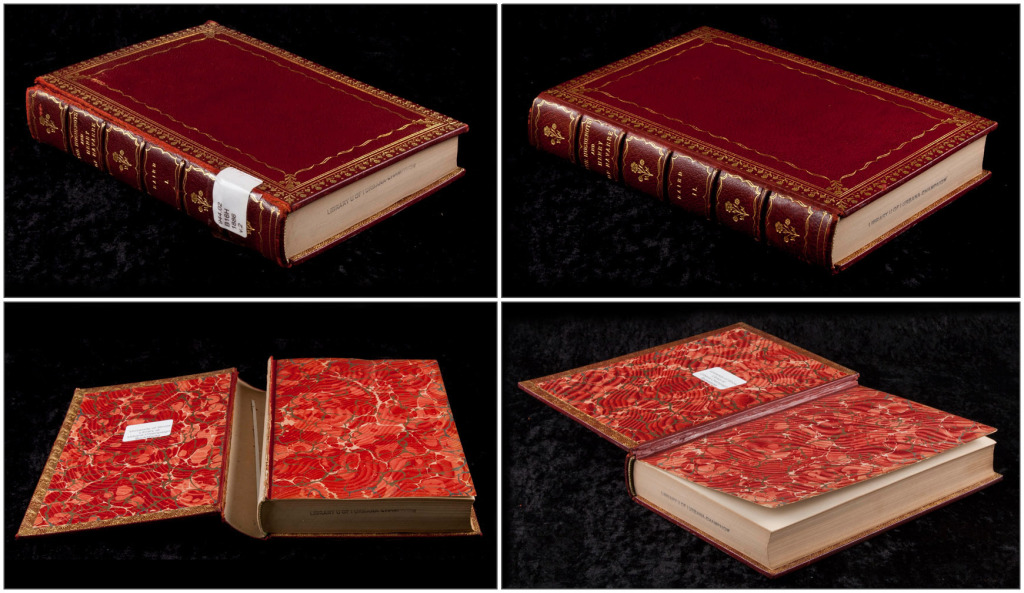

7. Conservation Conversations // Making an Old Book Whole Again by Jacqueline Scott

Jacqueline Scott had a slew of internships this past summer, which offered great material for the Conservation Conversations column on the blog. I particularly enjoyed this treatment of a binding in the collection at the Newberry Library in Chicago.

8. March // Bookbinder of the Month: Tracey Rowledge

I am so awed by the art work and bindings from Tracey Rowledge. Her responses to my interview questions were so thoughtful and inspiring. There is no mistake that she is a talented craftsperson with an impeccable ability to meld her artistic capabilities into her bindings.

9. Artist: Tomma Abts

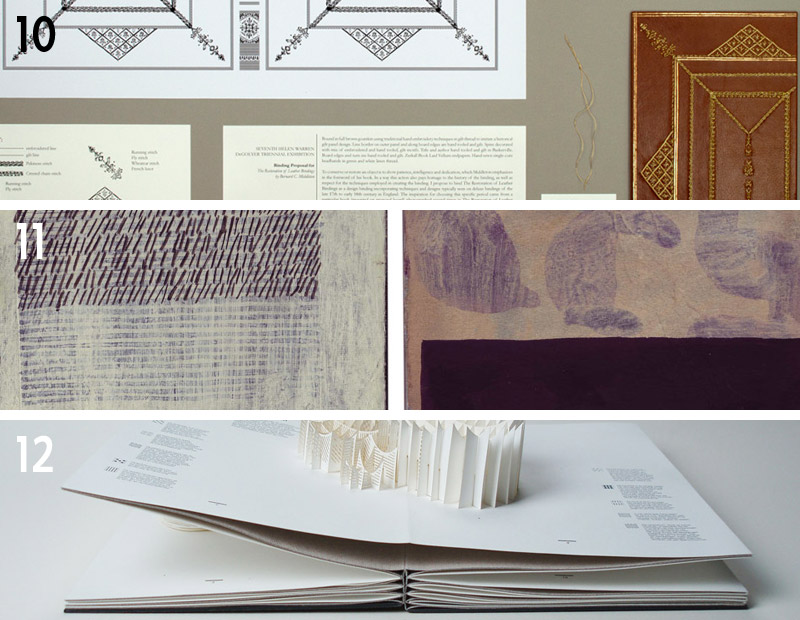

10. Seventh Triennial Helen Warren DeGolyer Exhibition and Bookbinding Competition 2015

As a first time participant in the DeGolyer Exhibit and Competition, I found the experience to be quite rewarding (despite the fact that I didn’t actually win anything). It forced me to execute an idea for a design binding in a new and more extensive way. This post goes into detail about my own proposal and the proposal from winner, Priscilla Spitler.

11. Artist: David Quinn

12. July // Bookbinder of the Month: Ben Elbel

An innovator in the field, Ben Elbel has continuously churned out variations on structures and has developed several new styles of binding. I am always looking forward to his next project; to read about the challenges posed by the binding and the elegant solutions he comes up with.

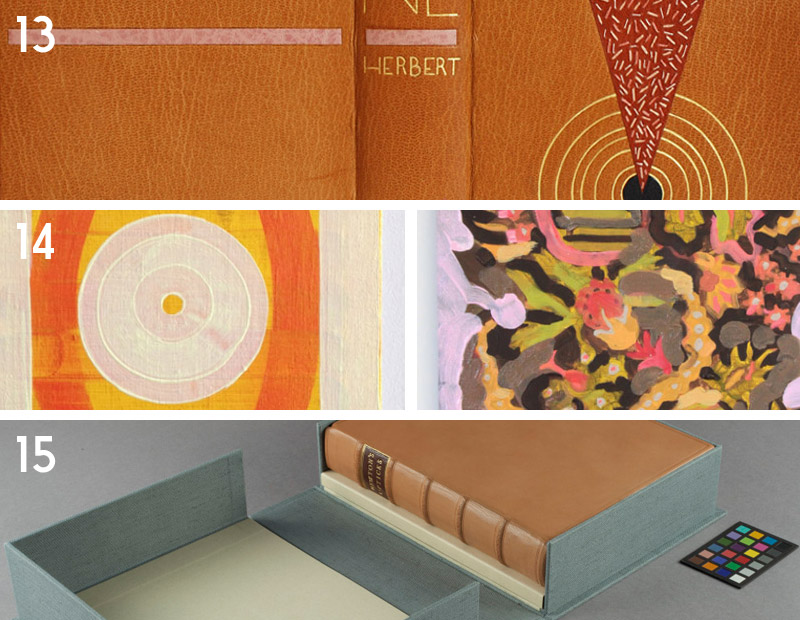

13. My Hand // Dune

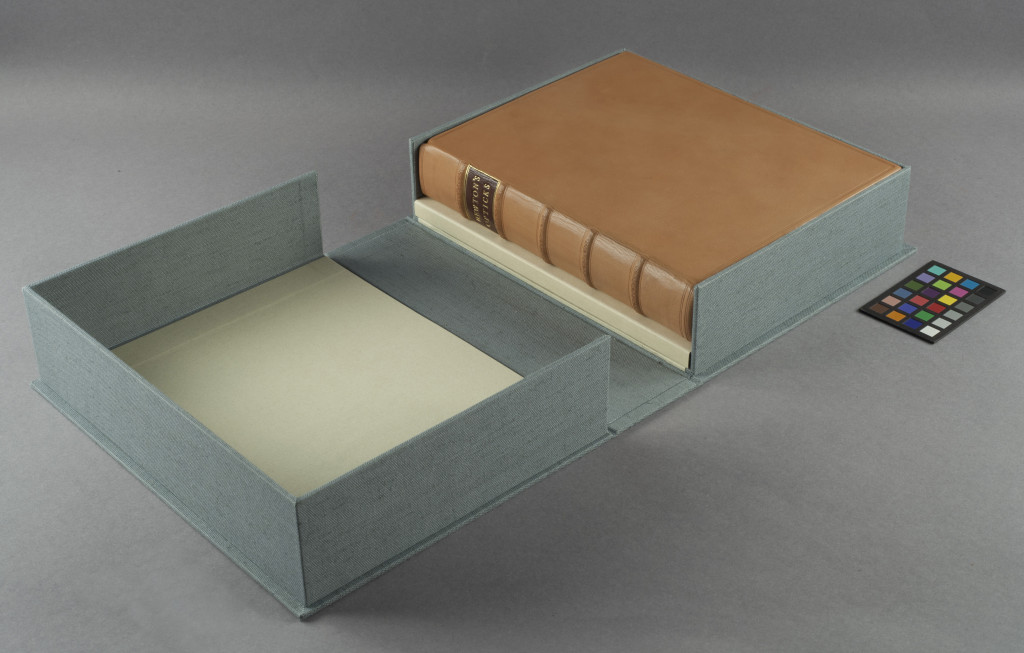

This year I finished my design binding for Dune, that was then accepted into the Guild of Book Workers Traveling Exhibit: Vessel. I am very pleased with the outcome of this binding, particularly with the edge decoration and the successfully gilt concentric circles. No easy task.

14. Artist: Lily Stockman

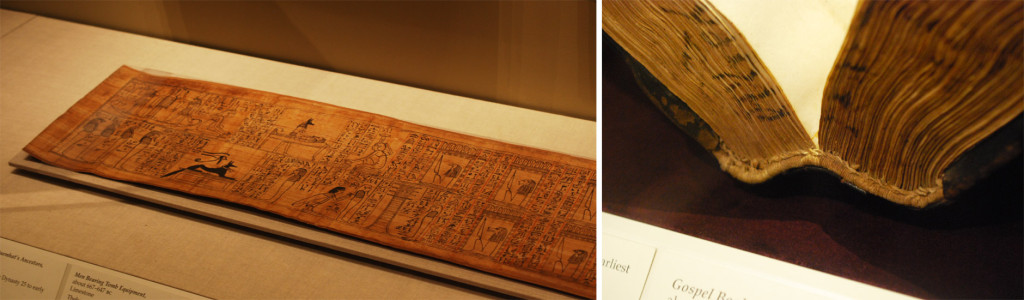

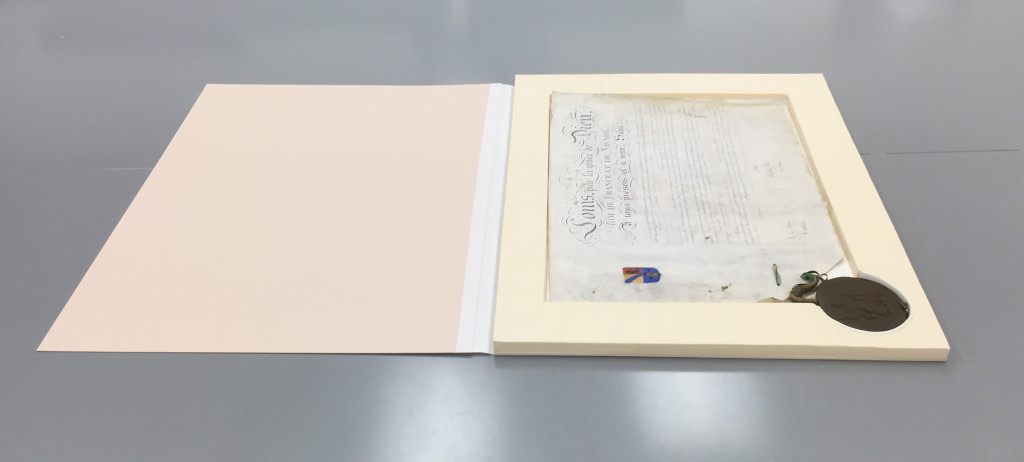

15. Conservation Conversations // The Continuum by Henry Hébert

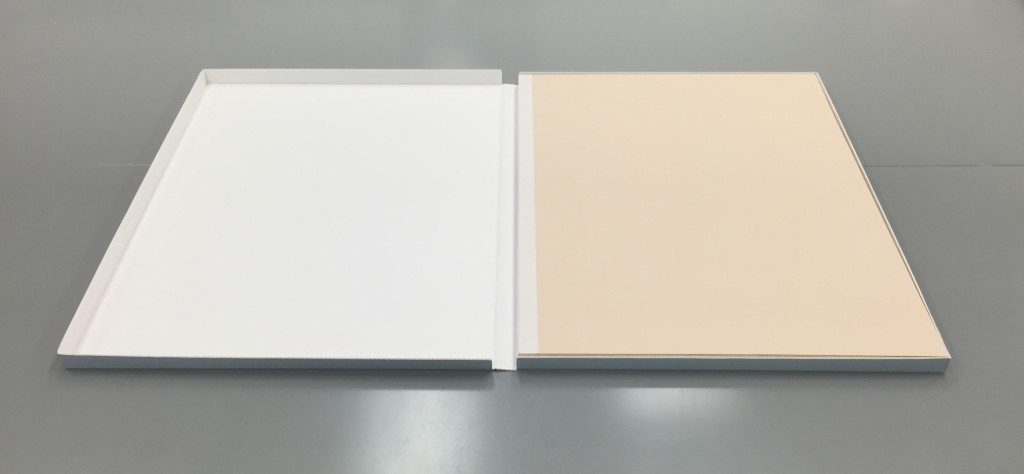

Henry Hébert has been writing for the Conservation Conversations post for 2 years now and has continuously delivered interesting and sometime hilarious content. The outcome of Henry’s treatment shared in this post is stunning. The new binding is well executed and is treated with respect to the binding’s historical content.

Happy New Year!