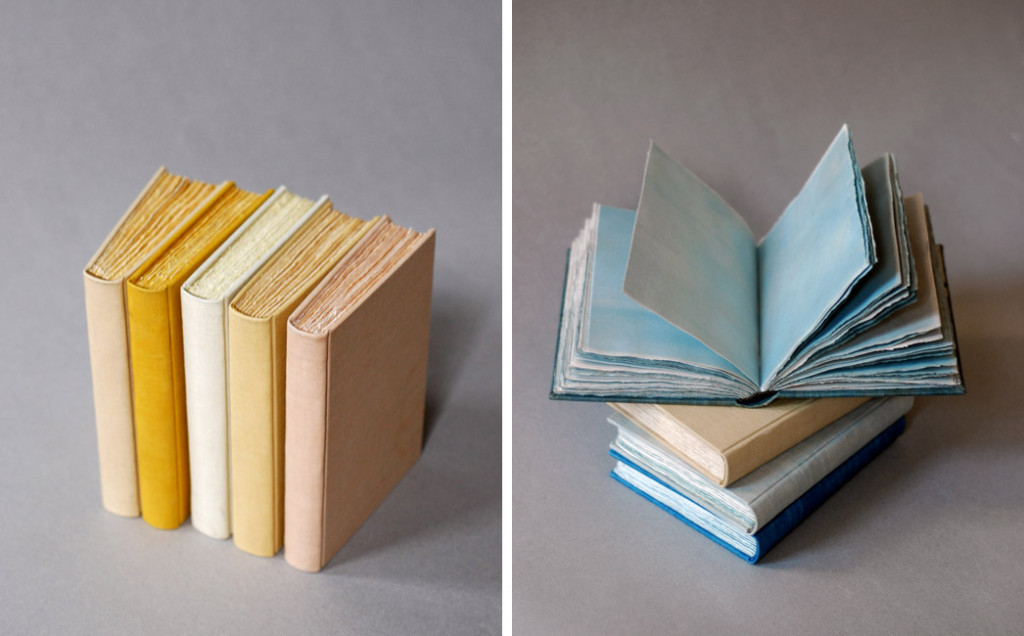

As a continuation from last week’s post, I extended the conversation on natural dyes with book artist, Natalie Stopka. During her time at the Center for Book Arts as a Van Lier/Stein Scholar, Natalie also completed a collection of case bindings, where each component beautifully represents the subtleties of natural dyes.

The variation between the different materials is subtle and beautiful. I wonder what your inspiration was for this project?

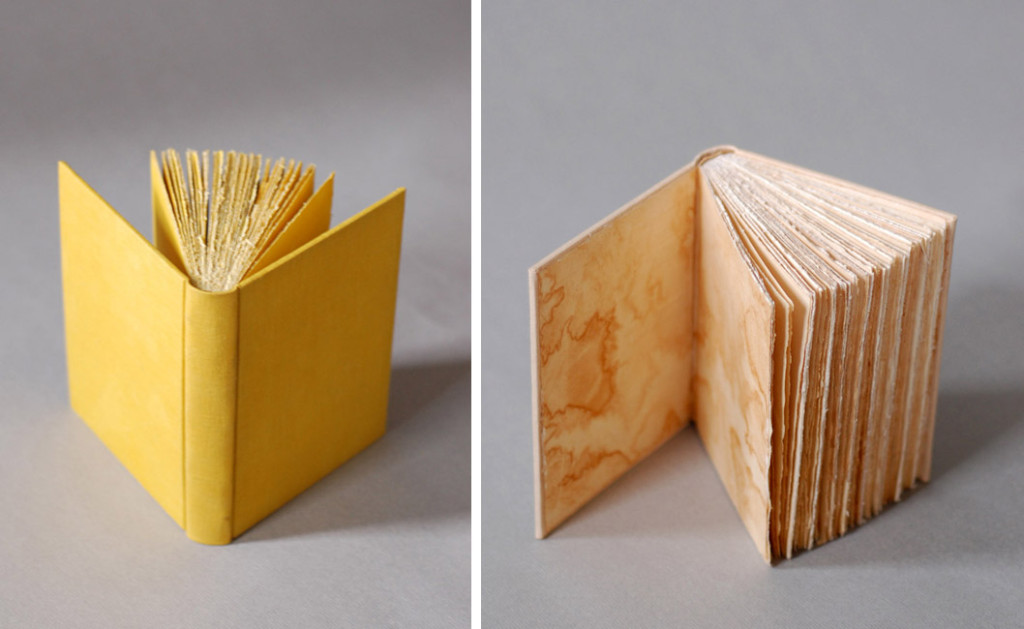

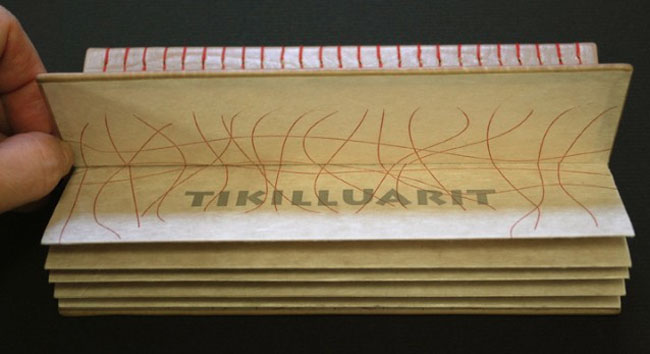

Besides my enjoyment of the process of foraging and dyeing with plants, I love the sympathy between natural dyes and fibers, as well as the resonance of using historical methods with historical materials. Prior to the discovery of synthetic dye in 1856, all books were decorated with naturally derived dyes, inks, and pigments. That is a lot of artistic heritage that has been largely supplanted in the past 150 years. I wanted to create some books that were all of a piece referencing that period just prior to the advent of synthetics, using a hollow-back structure with linen book cloth, hand sewn headbands, uncut pages folded down from full sheets, and, of course, natural dyes. I ended up binding a dozen books in different colors, partly as an exercise in honing my binding skills, as well as a continuation of my dye experiments.

Can you walk through your dying process from the creation of the pigments to the dying of the materials? Where did you learn these techniques?

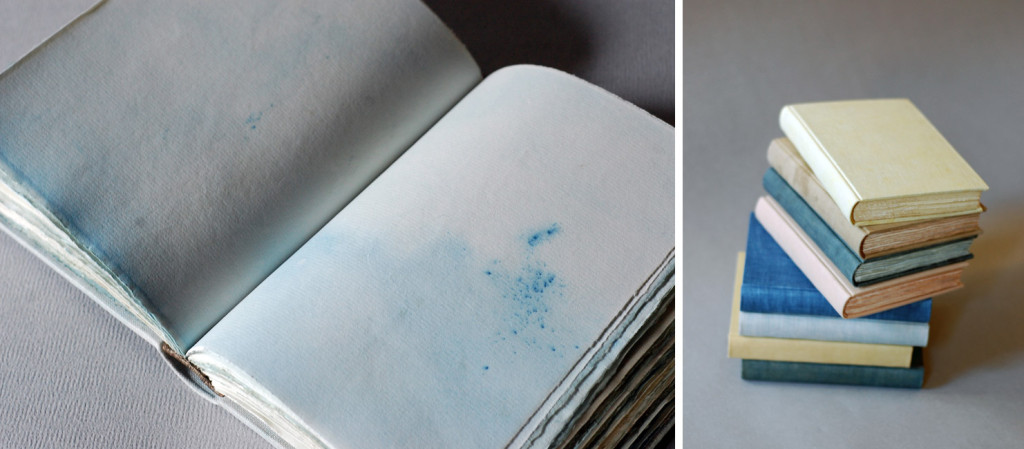

Beginning with the techniques I learned at the Textile Arts Center, I extended my natural dye experiments into bookbinding. There was some trial and error at first as I selected and mordanted paper samples. Papermakers generally color the pulp with pigment prior to forming sheets, so there is not a lot of information on how to dye paper, or how the dyes and mordants affect it over time. But paper is just cellulose fiber like many fabrics I had experience dyeing, so I jumped in. I decided to use Zerkall Ingres, which is quite absorbent due to its composition, but also has good wet strength. And when folded down it makes a lovely signature size.

The first step in dyeing is to source or collect plant material. In this case I used plants I foraged in upstate New York including oak leaves, cherry bark, Queen Anne’s lace, apple bark, and yarrow, the only exception being indigo. I chopped and soaked or simmered the plant material to extract the dye, then strained the dye liquor into a big stainless steel vat containing the mordanted paper and other book materials. After about 12 hours in the vat, everything was ready to carefully remove and dry.

As with my embroidered botanical illustrations, these books demonstrate the different shades of color (sometimes slight) that result when a single dye is applied to various substrates. The linen cover, silk headbanding thread, Zerkall Ingres pages, and linen binding thread were all dyed in the same vat. The endpapers were made from the uppermost sheet of paper in the bath, which became patterned by the evaporation of the dye. My favorite book was dyed with black cherry bark – I left the dye vat outside overnight, and a light frost left crystal patterns on the endpapers! Initially I expected the papers to take the dye evenly in a uniform shade, but most dyes were absorbed with a good deal of variation, making a richly toned surface.