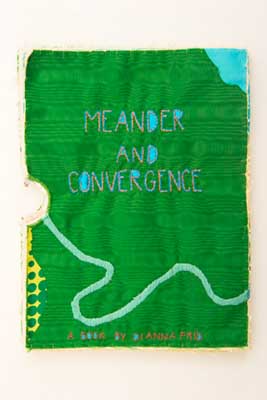

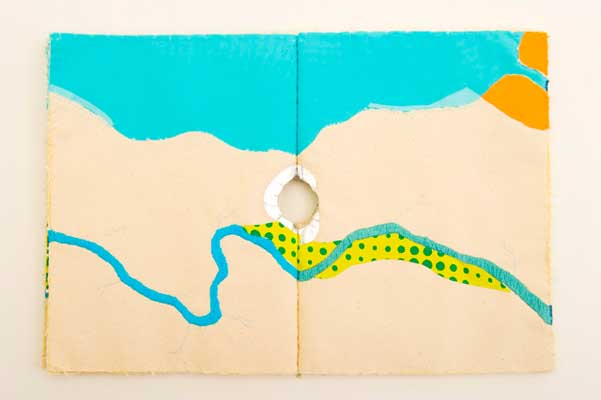

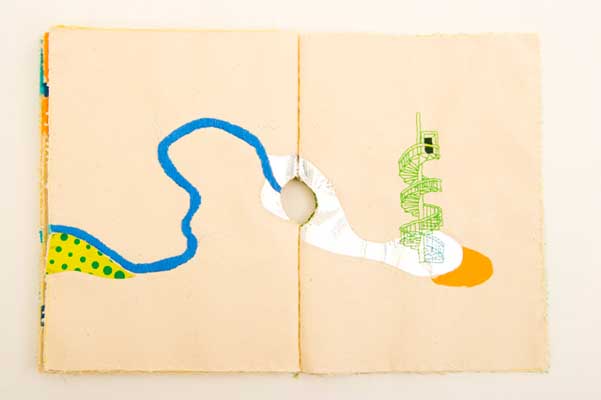

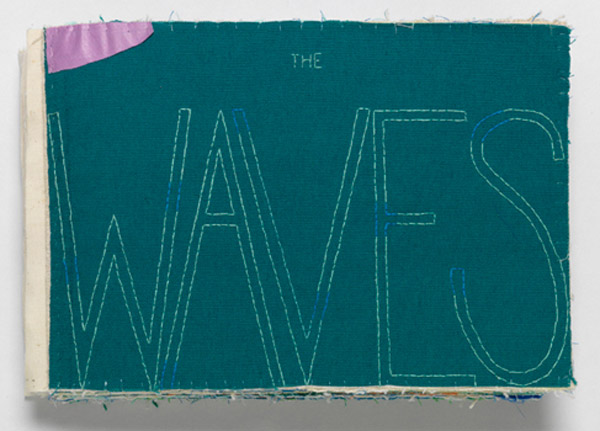

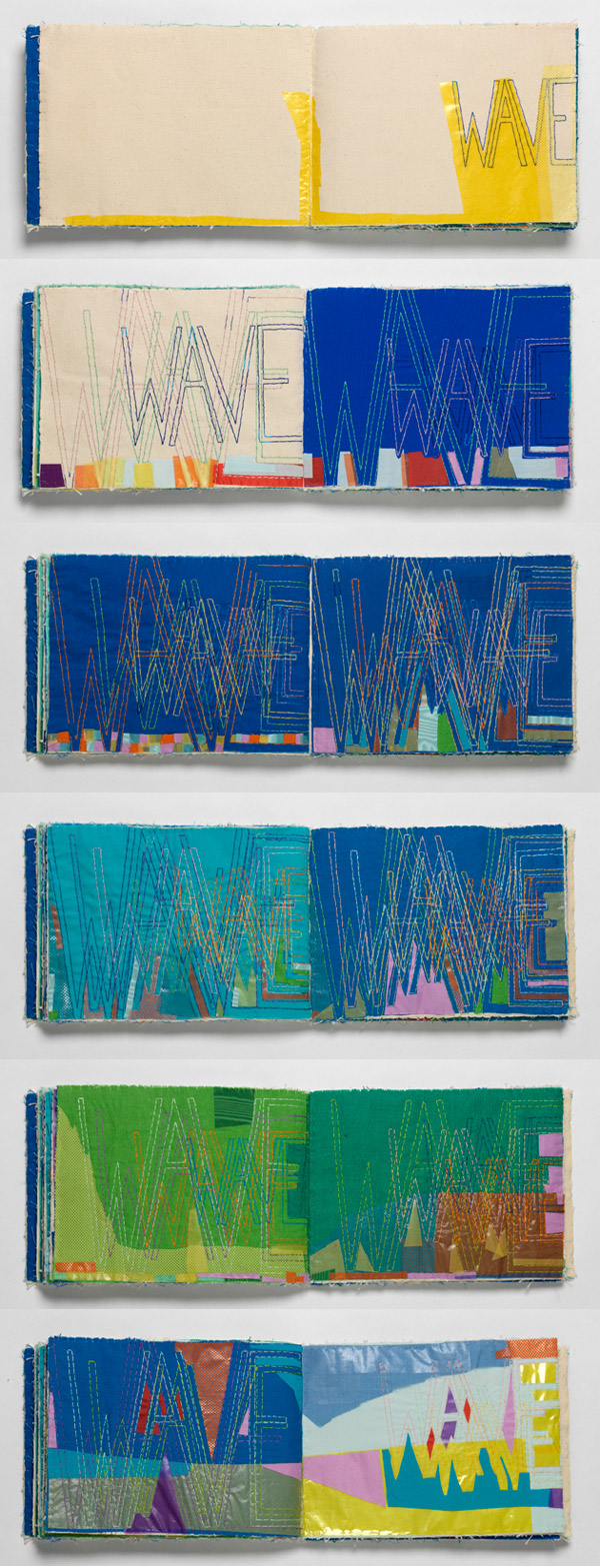

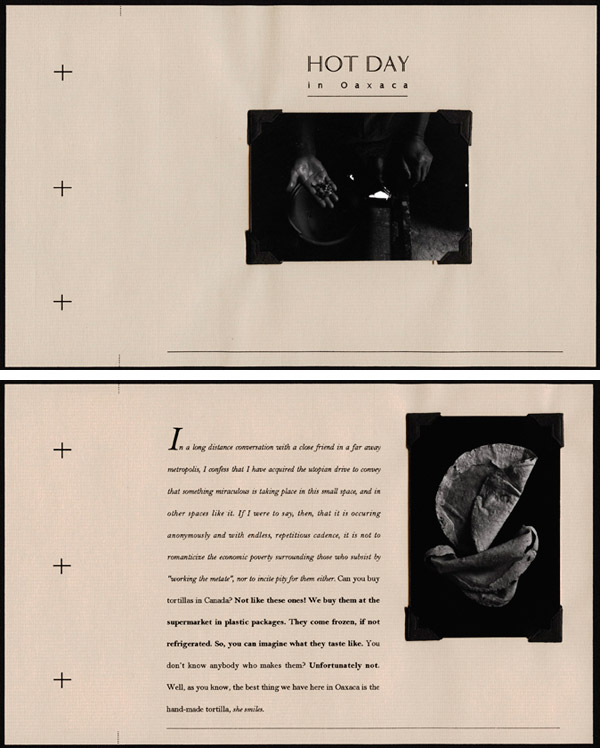

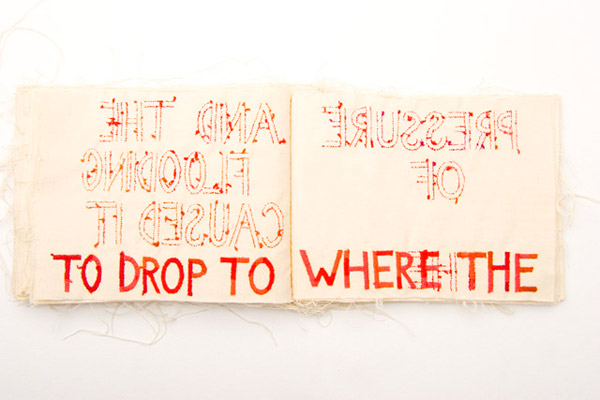

In 2007, Dianna Frid created Meander and Convergence using canvas and silk with hints of thread and foil. Imagery of rivers and staircases recur throughout Dianna’s work as symbols of time, cycles and finitude.

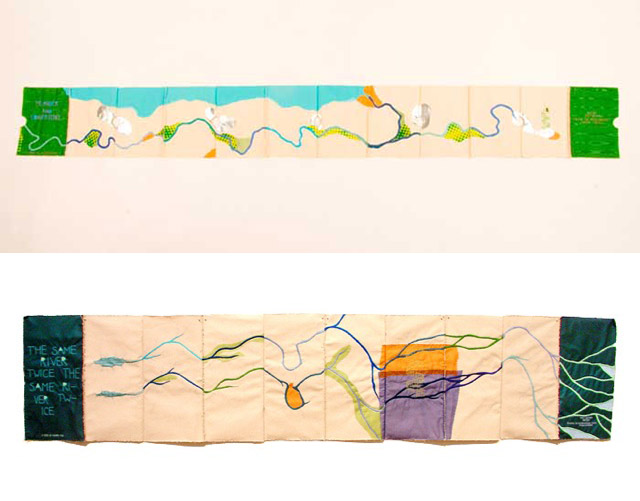

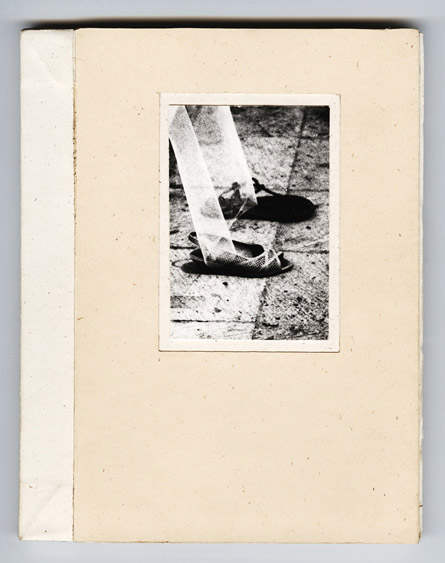

Below you can see the similarities between Meander and Convergence and The Same River Twice, The Same River Twice. Both artist books were constructed as an accordion structure and therefore the entire content can easily be seen at once. Each book also includes an embroidered image of a spiral staircase.

The staircase as a symbol has also appeared in Dianna’s sculptural and installation work.