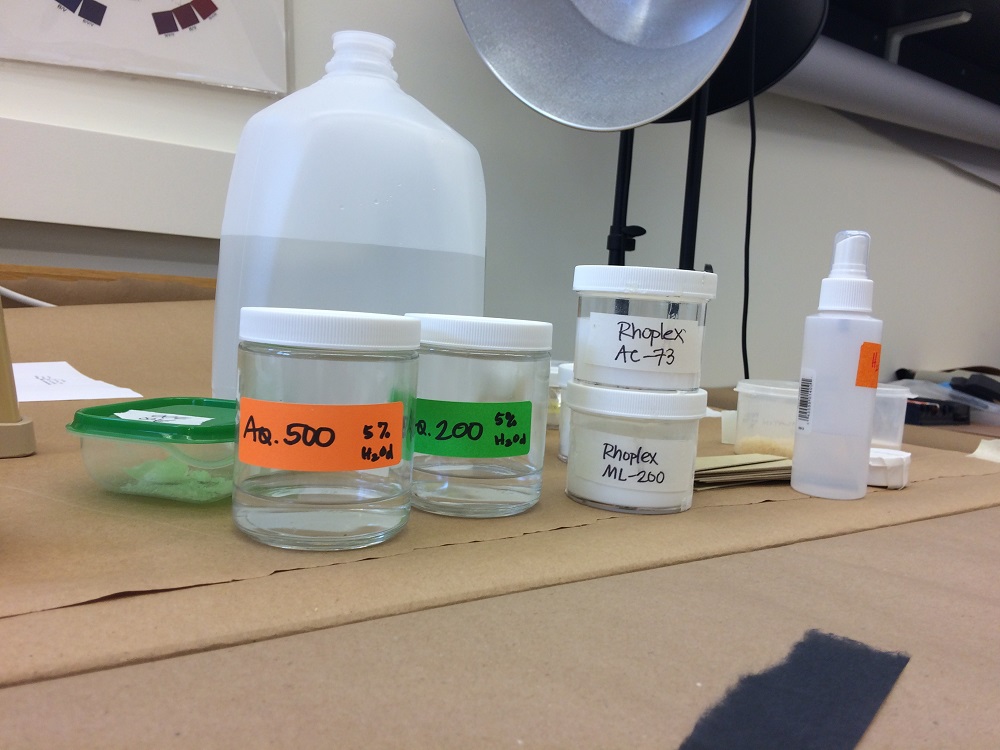

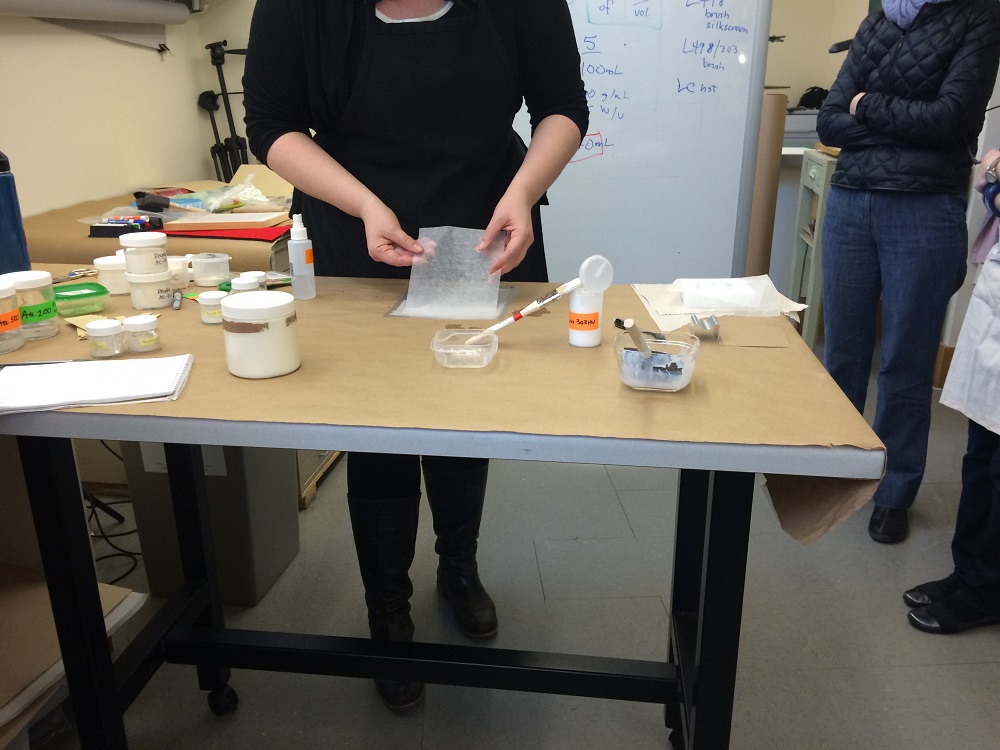

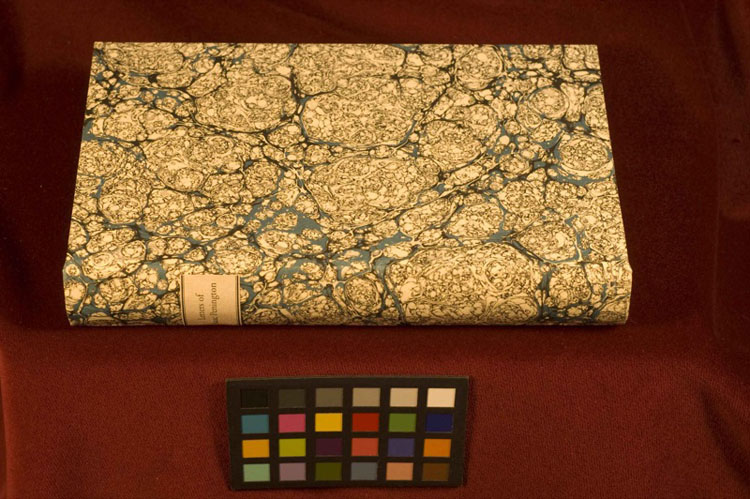

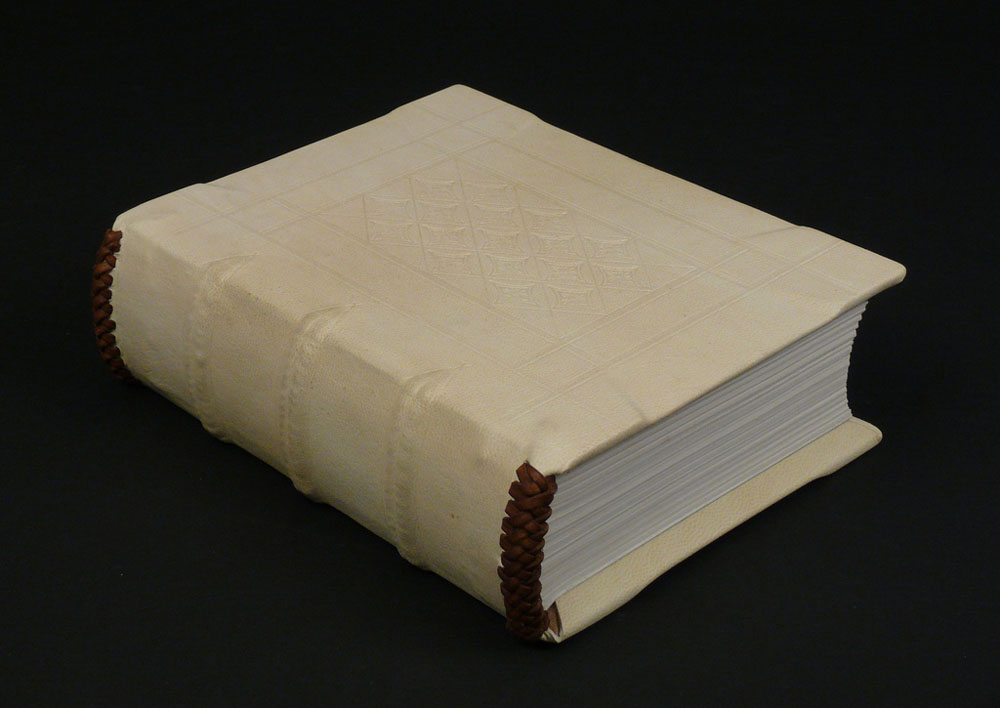

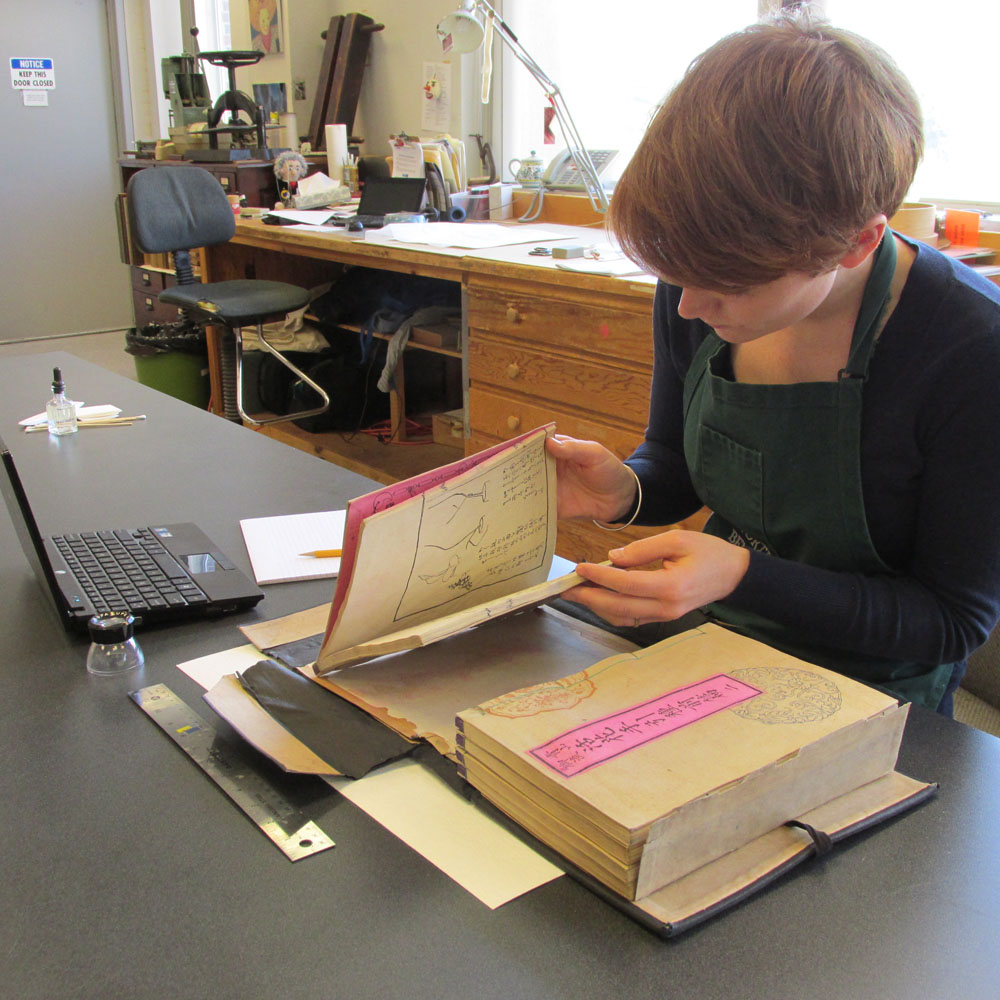

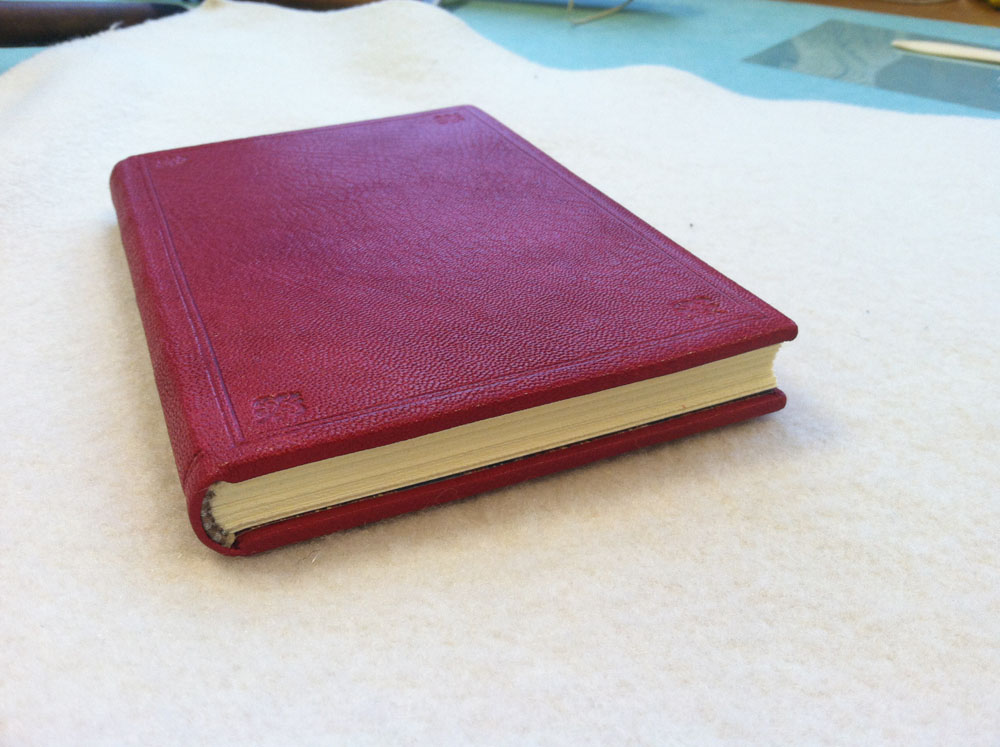

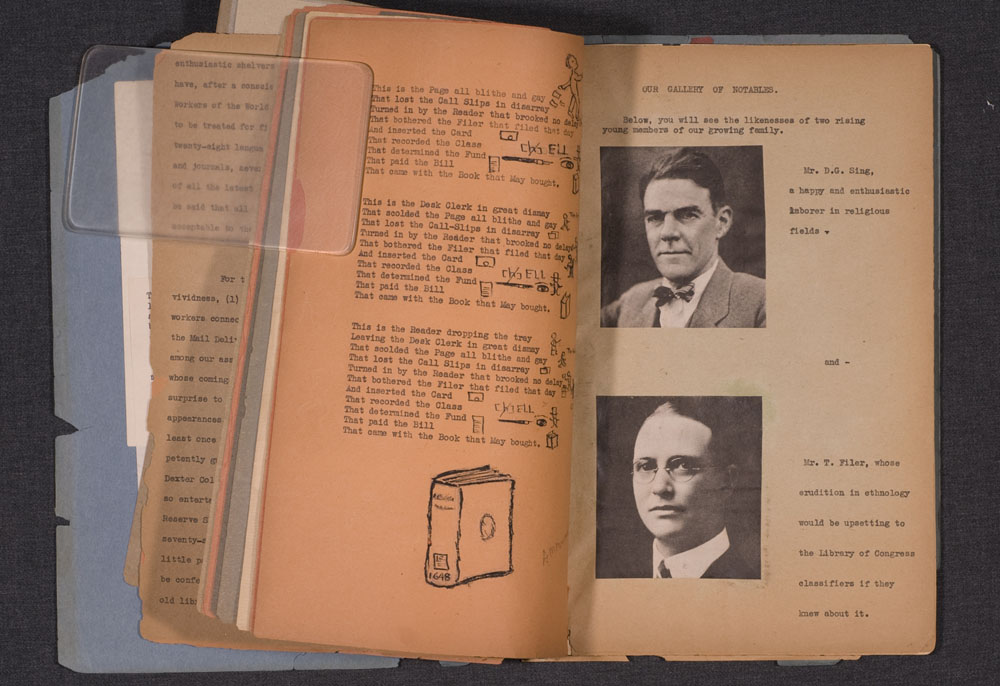

An Exquisite Corpse is a method of illustration invented by Surrealists in the early 1910s, where each collaborator adds to a composition in sequence usually without seeing the prior portion. Upon reveal this rule to hide the previous sequences offers up an abstract and amusing portrait. Each student created a plaquette covered in neutral leather (we used Harmatan Terracotta and Brown goatskin) and also completed the “head” portion of the figure. The plaquette’s were about 18in x 6in; allowing each participant to cover a 6in square portion of the board.

The project spanned over 3 months as each participant received and worked on their portion over the course of a month. At the end of May, the finished pieces were on display as part of NBSS’s Student & Alumni Show, an annual exhibit that showcases work from current students and alumni from the various programs.

I had the pleasure of receiving the finished pieces and bringing them back to the students. We gathered around one another as each student revealed the unique and strange characters that developed over the course of the project. Each piece is displayed below with a brief description from each collaborator remarking on their concept and use of materials.

Jeffrey Altepeter

Jeffrey AltepeterThe robot head was inspired by my son’s fascination with mechanical and technological design and construction. It is made up of traditional leather decoration techniques—leather onlays, tooled with gold leaf, foil and carbon.

Samuel Feinstein

Chicago, IL

Gold and blind tooling.

Lang Ingalls

Crested Butte, CO

I opted for humor in my approach to the Exquisite Corpse. The design concept was to depict bird legs: the initial tests were for tooling in the positive; it became clear that the negative space would be more interesting. I used four sizes of “dots” in gold foil to produce the background behind the legs. Repetition and rhythm became the focal point.

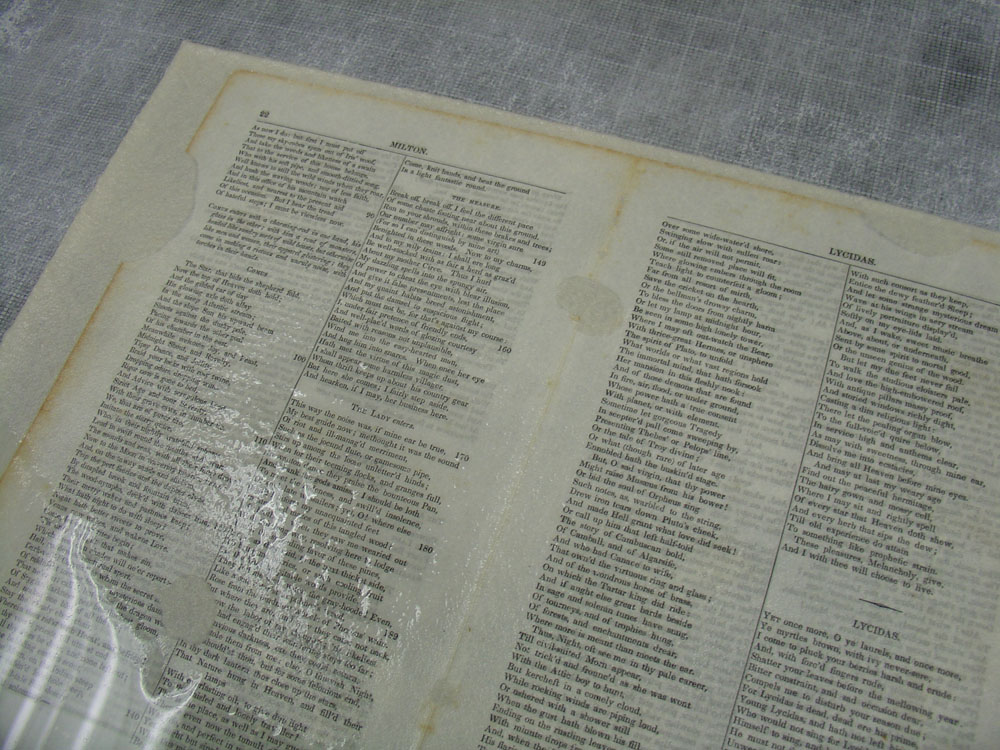

Emily Patchin – Barbara Adams Hebard – Athena Moore

Emily Patchin

Emily PatchinThis head was created as an onlay piece. The main portion was cut out of navy blue goat skin, pared thin. The sections for the eye, ear, and ghosts were all cut out, and their edges beveled on the flesh-side. Light blue leather for the eye and ear were glued to the back before pasting to the base leather. The ghosts were cut out from parchment; their faces backed with thinly pared gold leather, and painted with watercolor before being glued in place. The outline of the original drawing was then blind tooled over the leather. The intention behind the design was to look at intense personal struggles (depression, intrusive thoughts, insomnia) through a lens of whimsy and humor.

Melrose, MA Melrose, MAWhite alum-tawed goatskin onlay with blind tooled details, inspired by the shape of an Early Cycladic marble female torso (2800-2300 BC, Keros-Syros Culture). Flanking the torso are shapes commonly found incised on Early Cycladic pottery, a spiral and a two-headed ax, executed in surface gilding.

Athena Moore

Somerville, MA

My materials were leather and hand-cast paper (made by the artist). The concept was a bit literal, since I had the last portion and was finishing the body with the legs, but I was inspired by a particular set of medical prints from Yale’s collection.

Jonathan Romain – Erin Fletcher – James Reid-Cunningham

Jonathan Romain

Jonathan Romain

a shapeless face, 18 karat gold, palladium, and ascona onlay

Erin Fletcher

Boston, MA

I wanted to created something really playful with my portion of the plaquette. When I saw no indication of where to begin, I chose to create a headless girl with comically long arms. The girl’s dress is a series of blind tooled onlays in pink and purple goatskin and white buffalo. Her skin is gold tooled. And the blood spurting from her headless stump is painted with red acrylic.

James Reid-Cunningham

Cambridge, MA

The design is largely non-representational, with a vague suggestion of legs. Otherwise, there is no concept. Tooled in gold and metallic foil, with inset lines of white box calf.

Mary Grace Whalen – Eric Alstrom – Penelope Hall

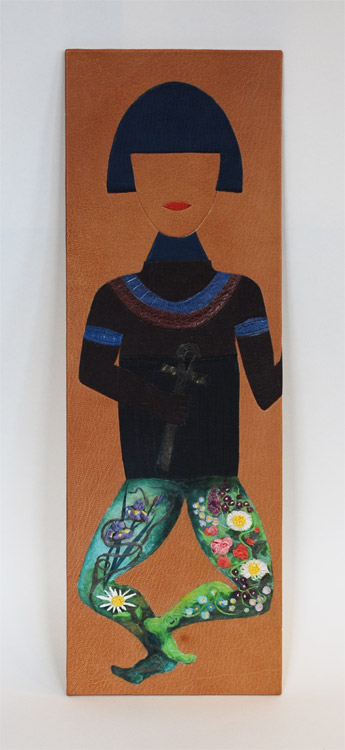

Mary Grace Whalen

Mary Grace Whalen

Blue Pageboy, a leather tool-edged onlay made of goatskin is inspired by the Russian pioneer of geometric abstraction, Kazimir Malevich’s costume design and his Yellow Man painting. Blue Pageboy gives off a theatrical and mysterious vibe. Who is s/he? Only the body will tell!

Eric Alstrom

Okemos, MI

After many ideas, I kept coming back to the idea of ancient Egypt and their exquisite corpses. My design is based on various historic paintings, but did not copy any single on in particular. The design is made from various colors of goat painted with acrylics and blind tooled

Penelope Hall

Kingfield, ME

Inlay consisting of glazed earthenware, scraps of Thai papers, and wheat paste. Colored with watercolor. Additional adhesives used are E-6000, and Jade 403 PVA. Finish coat on the inlay is SC 6000 acrylic polymer and wax emulsion.

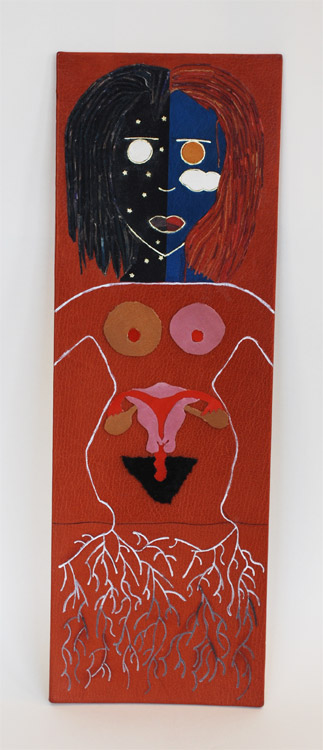

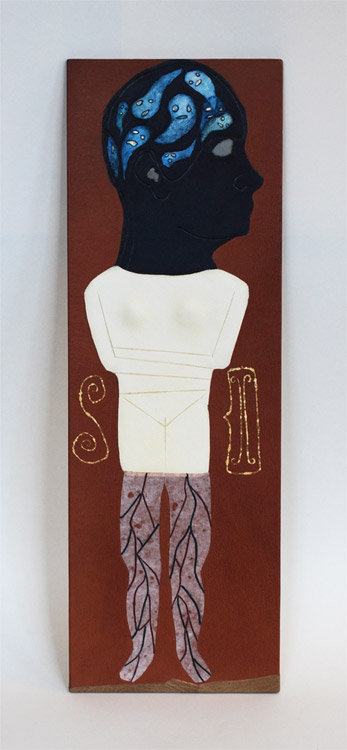

Nicole Campana – Jan Baker – Colin Urbina

Nicole Campana

This design was inspired by nothing more than a common theme in much of my art: day and night. I’m drawn to the color palette each time presents and the way in which our perceptions of those colors change as the light does. The techniques utilized are predominantly onlays and gold tooling, however a variation of the lacunose technique and an Ascona tool were used for the hair.

Jan Baker

Providence, RI

what i lost this year:

– my ovaries

– my fallopian tubes

– my uterus

– all of my hair

– and my brother

Colin Urbina

Boston, MA

When I’m sketching, I often come back to the roots of a plant. For this project I decided to attempt the same type of free flowing, loose, many-from-one nature of these sketches with traditional gouges. Using five or six tools I built up the legs of this plaquette, and then added acrylic paint into them that gets darker as the roots go lower. The dirt is represented by grain manipulation with sandpaper, changing the surface of the leather and giving it a different look and feel.

Peggy Boston – John Nove – Shannon Kerner

Peggy Boston

My inspiration for this project came from a group of mustachioed, high-collared, quirky members of the Viennese Secessionist art movement. This movement was part of the golden age of illustration and graphic design in Vienna and Germany from 1897 to 1918. Their main influences were derived from William Morris and the English Arts and Crafts movement which sought to bridge the applied and fine arts. The Secessionists favored hand-made object opposing machine techniques. Hand tooling and acrylic paint.

John Nove

South Deerfield, MA

The initial description of the project attributed the Exquisite Corpse to the Surrealists. My concept was of a Magritte-ian gentleman – fine suit, hands crossed in the standard coffin pose holding the usual flower — but then with an amphibian’s green gnarly ‘hands’. Carbon tooling and goatskin onlays.

Shannon Kerner

Easthampton MA

The vivid colors on the chubby tum were used to inspire whimsy, as well as the funny shape of the legs, which took inspiration from the cartoon Invader Zim, a silly plot animation focusing on an alien sent to Earth and meant to blend in. Stars: gold and palladium mixed together is a challenging medium to tool as they are different weights, but the outcome is very rewarding and attractive. Leather onlays, gold and palladium tooling.

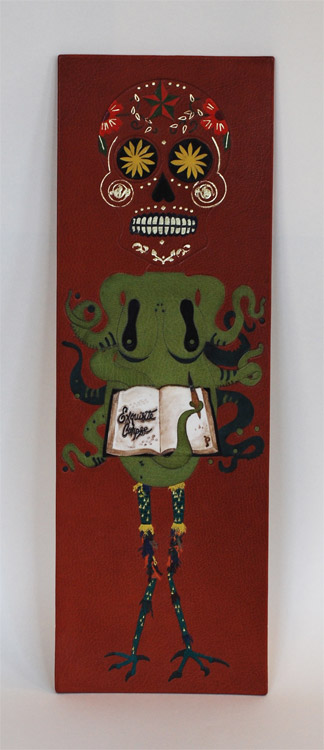

Todd Davis – Jason Patrician – Jacqueline Scott

Todd Davis

The design of this head is inspired by the sugar skulls used as part of the Mexican celebration of Dia de los Muertos (day of the dead). On that day, these skulls, made of sugar, are part of an altar made to honor and celebrate dead ancestors, particularly children. Blind tooled outline filled with raised, ascona, and back-pared onlays. It is finished with blind and lemon gold tooling, and surface gilded teeth.

Jason Patrician

New London, CT

I wanted to stay true to the surrealist exercise of the exquisite corpse by combining the distorted human figure and nature. For my design I chose the octopus, the master of disguise, which doubles as the female torso. Leather onlays (Harmatan and Pergamena), vellum inlay (Pergamena) with walnut ink wash and Prismacolor marker detail, blind tooling throughout.

Jacqueline Scott

Somerville, MA