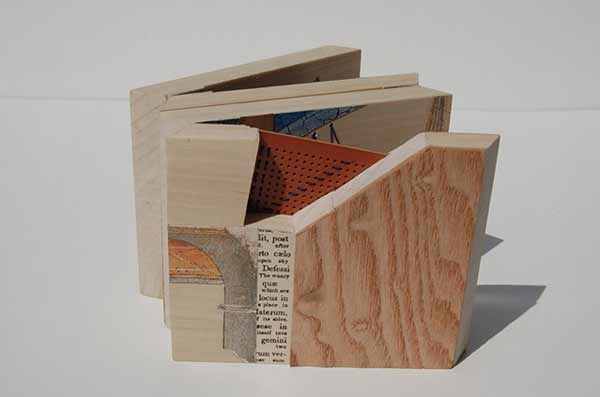

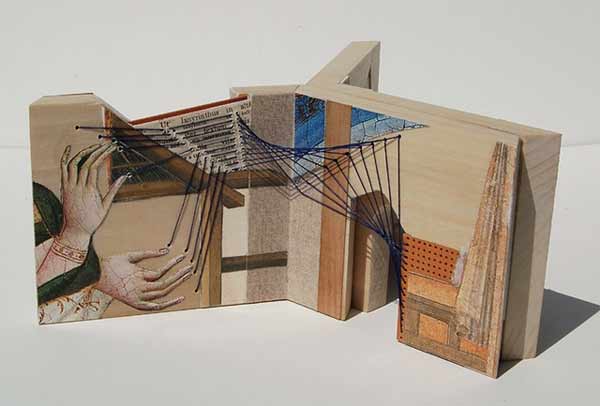

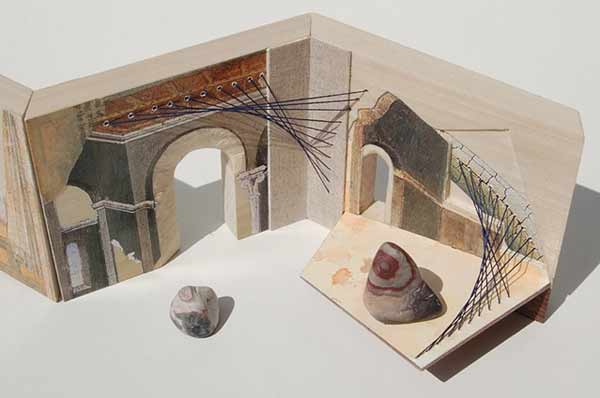

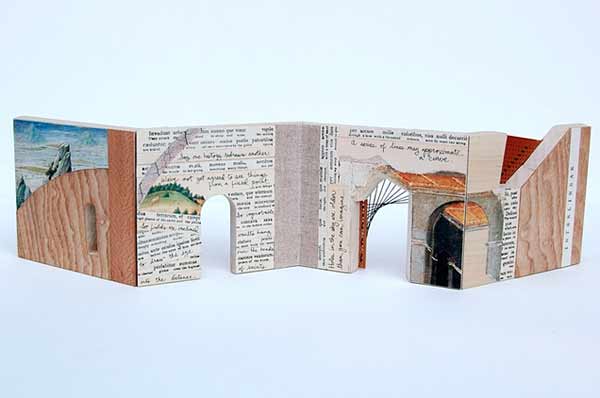

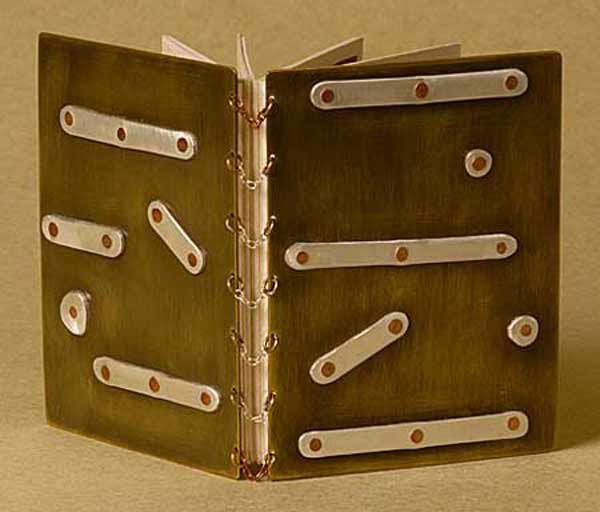

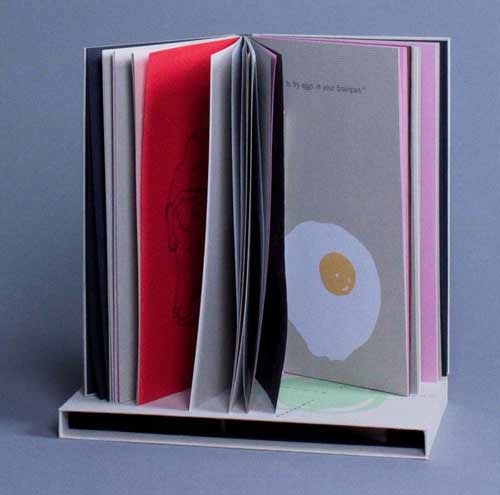

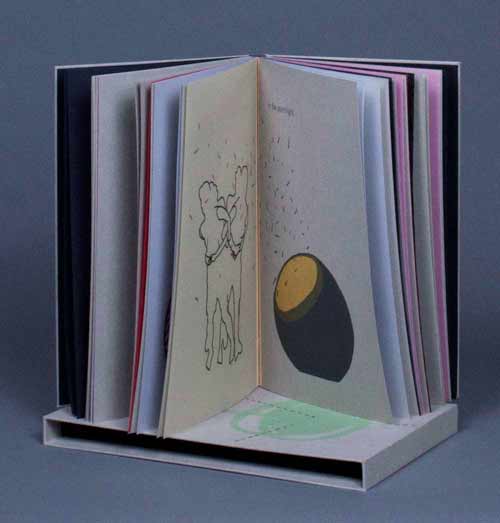

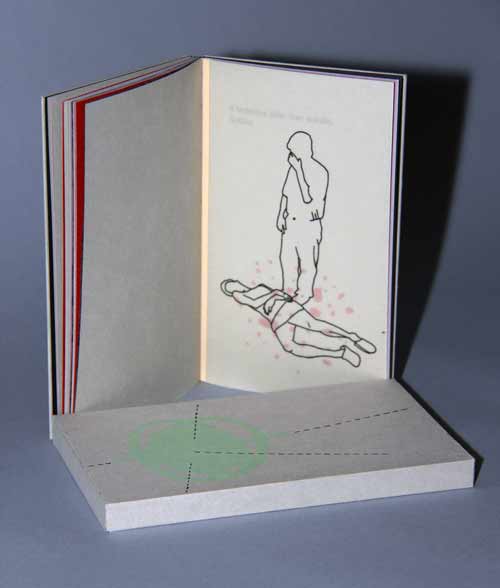

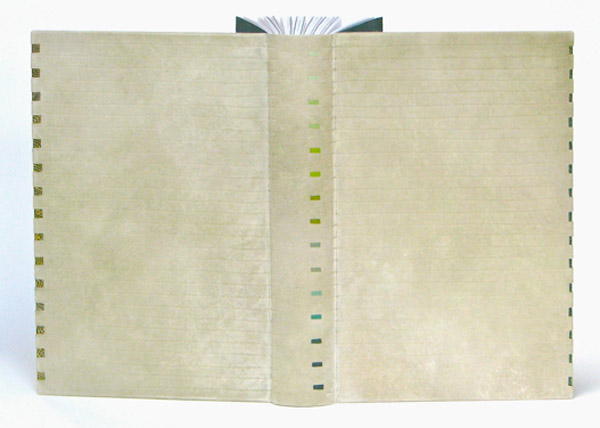

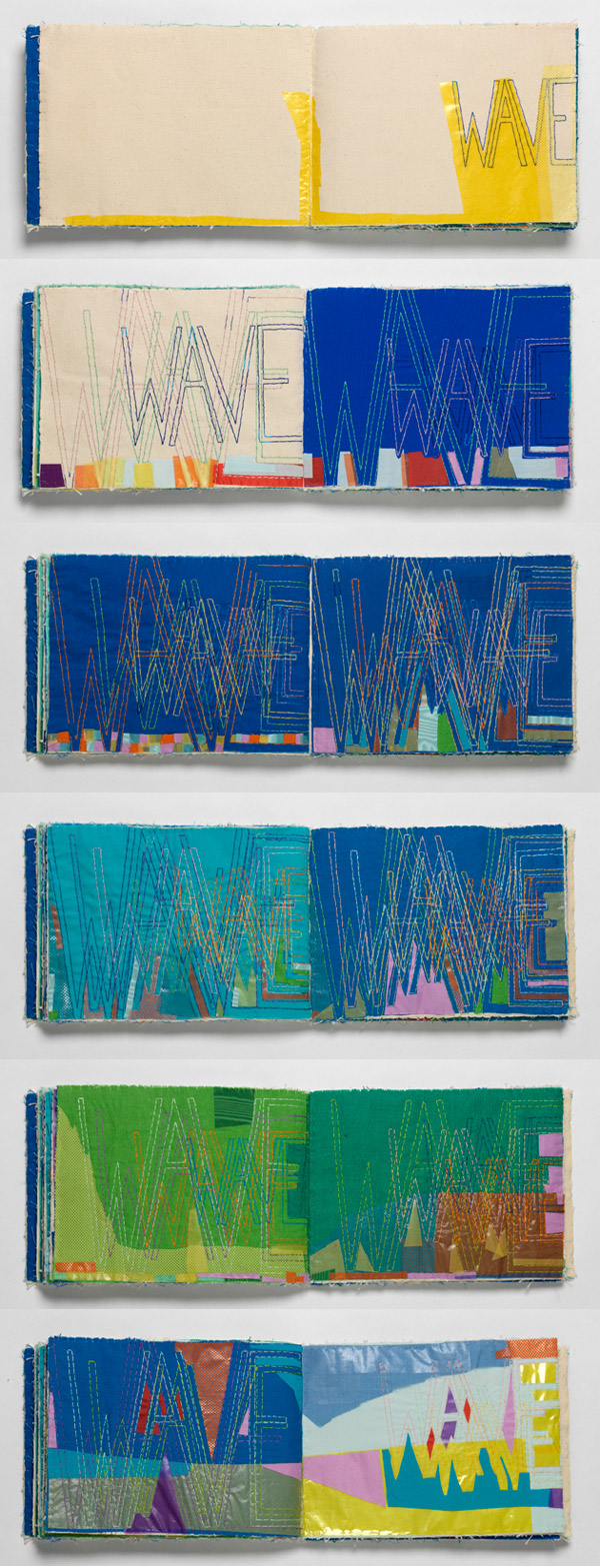

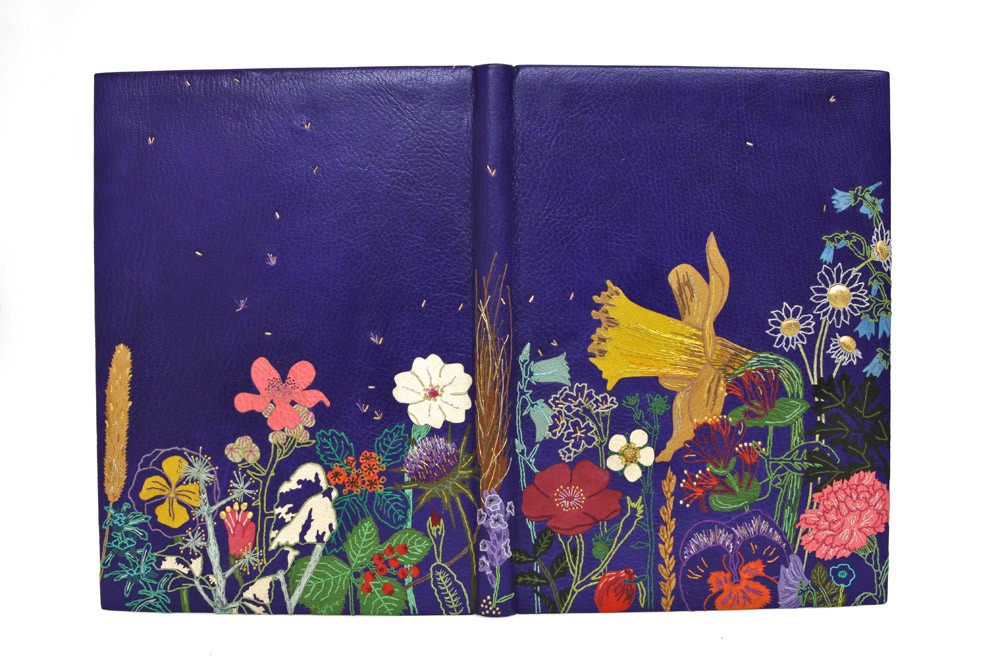

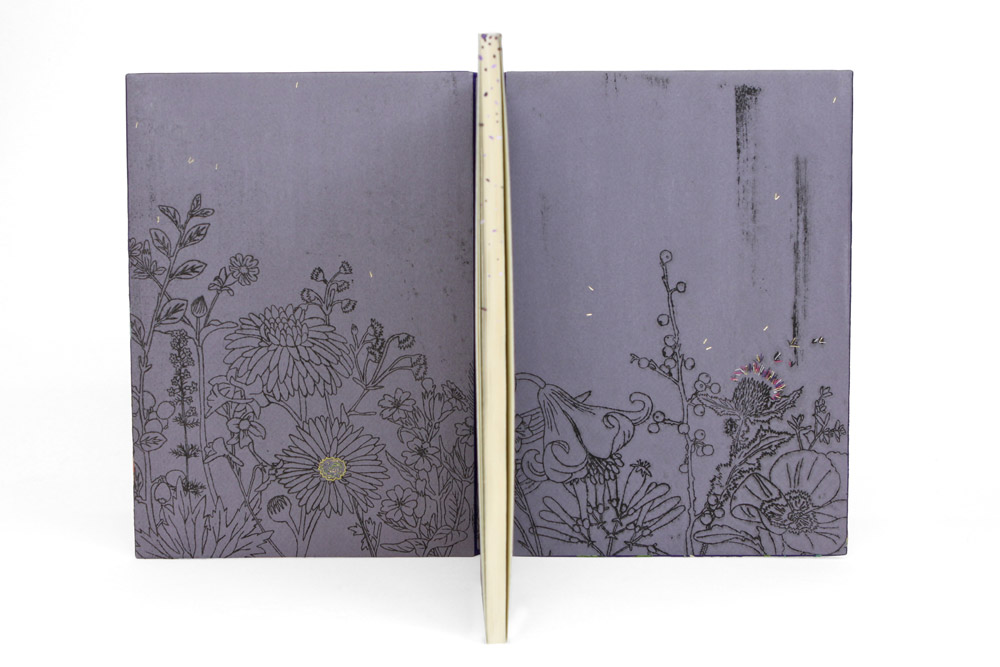

In 2011, Susan Collard crafted Interlinear, a wooden accordion-like structure collaged with various imagery and texts. I’m particularly attracted to the inclusion of delicate embroidery threads; connecting the illustrations in a playful manner and drawing the viewer’s eye from page to page through doorways and into secret compartments.

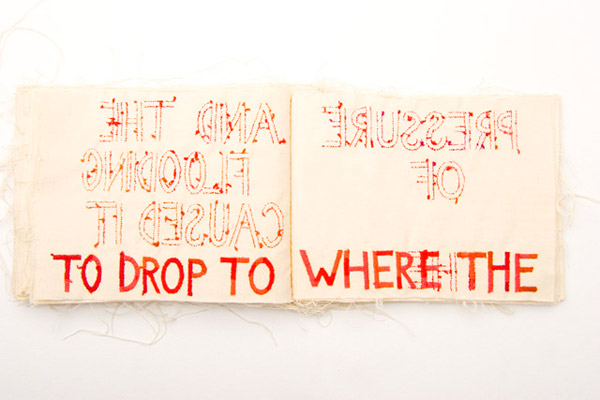

During my first year at North Bennet Street School, the students were invited to aid in the set-up of the Marking Time Exhibition at Dartmouth College. It was here that I first saw and played with Susan’s work. As we gathered around her work, we dropped one of the steel balls to investigate the hidden channels and pathways between each page.

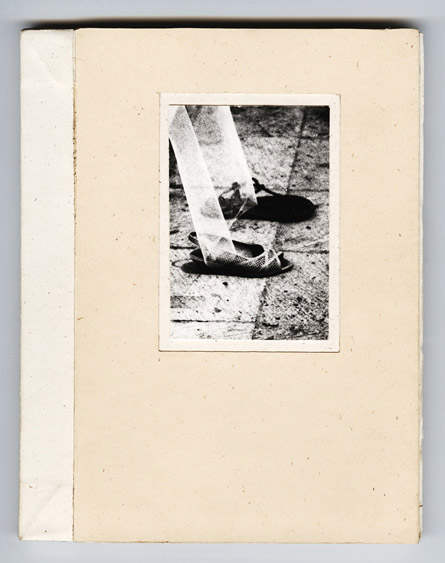

Read the interview after the jump. Come back each Monday during the month of May for more posts about Susan’s work, which include in progress photos for A Short Course in Recollection and more detailed images of Camera Obscura.