Mending tears is a treatment that book and paper conservators utilize nearly every day. For this reason, wheat starch paste is one of our best friends at the bench – a dependable go-to, especially when paired with an appropriate eastern paper. Unfortunately, this reliable standard is is not always an option – the media may be soluble, the paper difficult, the work space less than ideal.

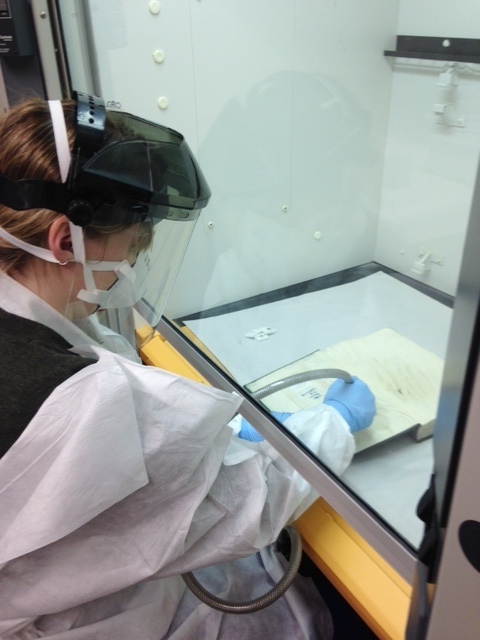

Luckily, there are other routes to take! A possible solution to one or all of these issues may be adhesive pre-coated repair materials. Recently, I had the pleasure of taking a two-day workshop at Dartmouth College taught by Sarah Reidell, Associate Conservator for Rare Books and Paper at the New York Public Library on exactly this topic.

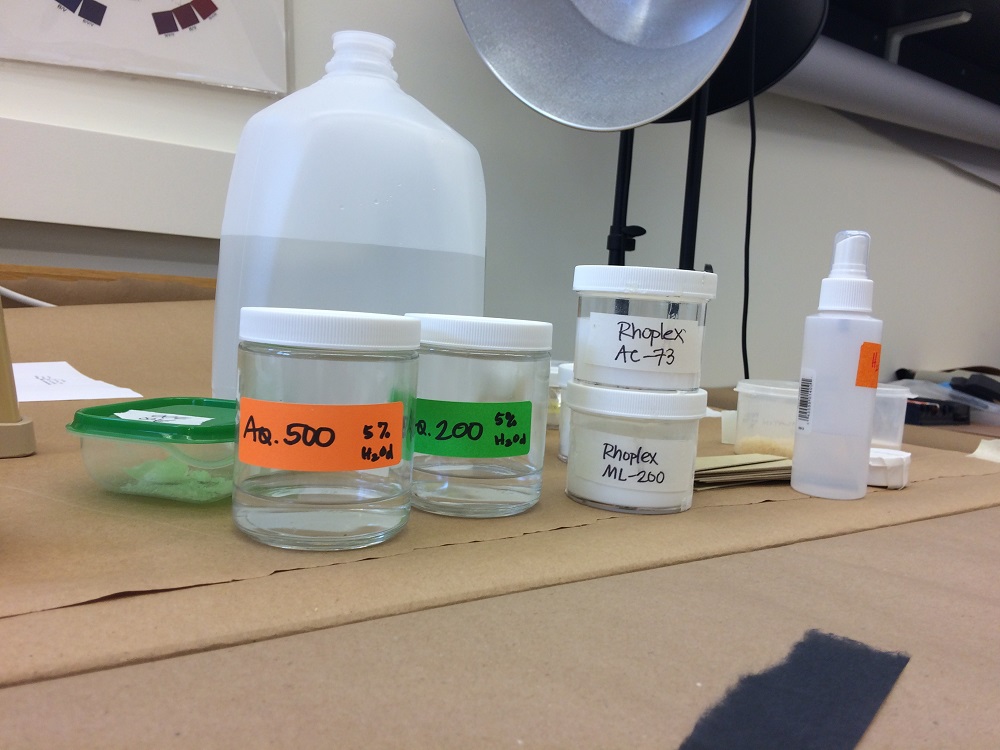

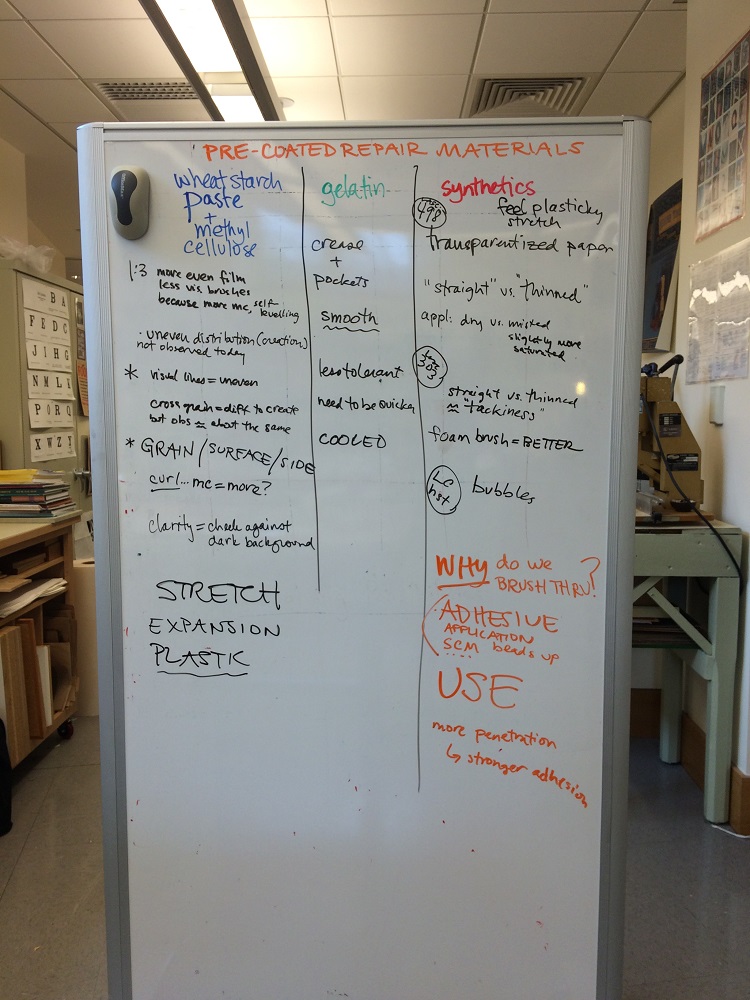

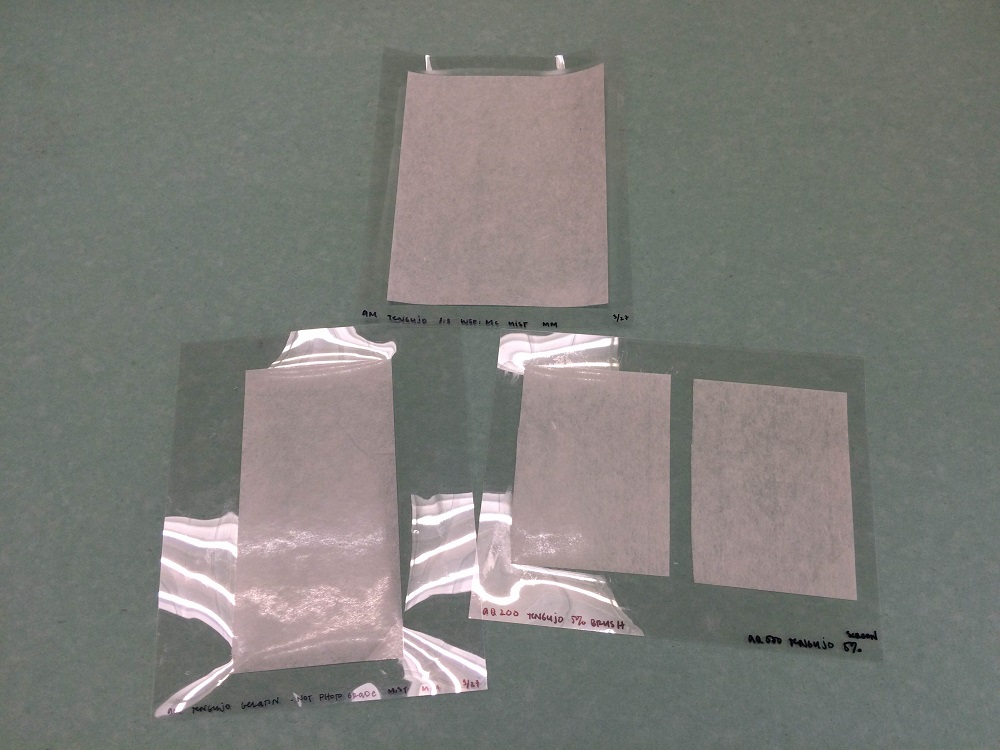

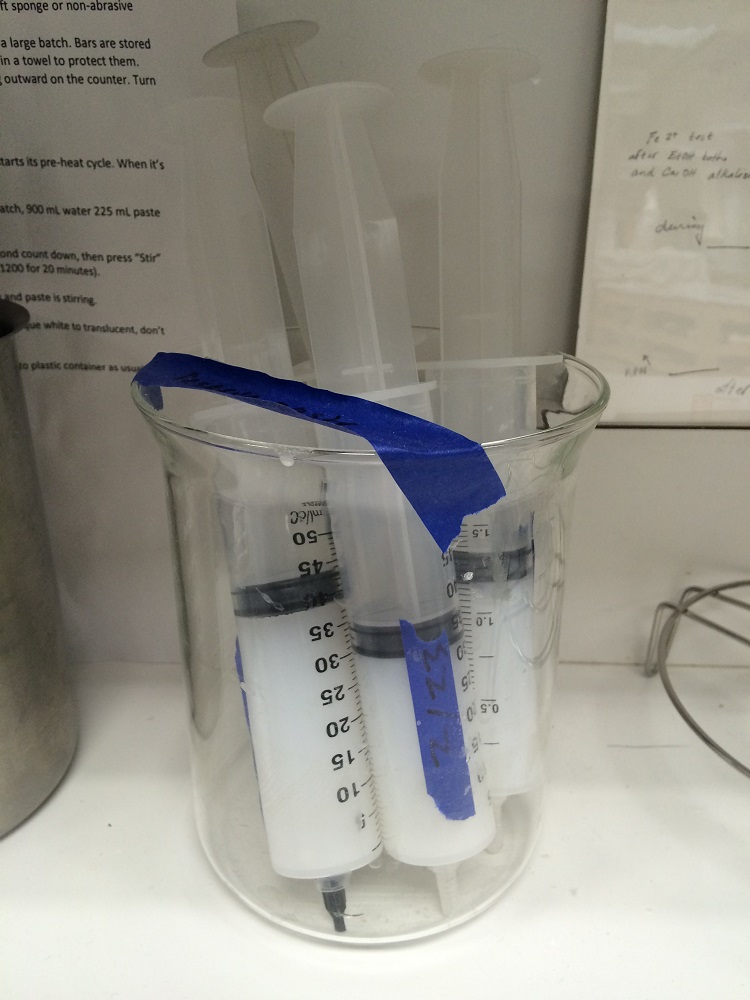

Pre-coated repair materials can be prepared with a huge number of adhesives – starches (wheat starch paste), cellulose ethers (methyl cellulose, sodium carboxymethyl cellulose, hydroxy propyl cellulose), proteins (gelatin, isinglass), synthetics (Aquazol, Lascaux 303HV and 498HV, Rhoplex, Avanse, Plextol, Texicryl) and in some cases, a combination of more than one. These adhesives can be applied to any number of repair papers with a variety of application methods. This makes the possibilities fairly endless, which is almost equally helpful and daunting.

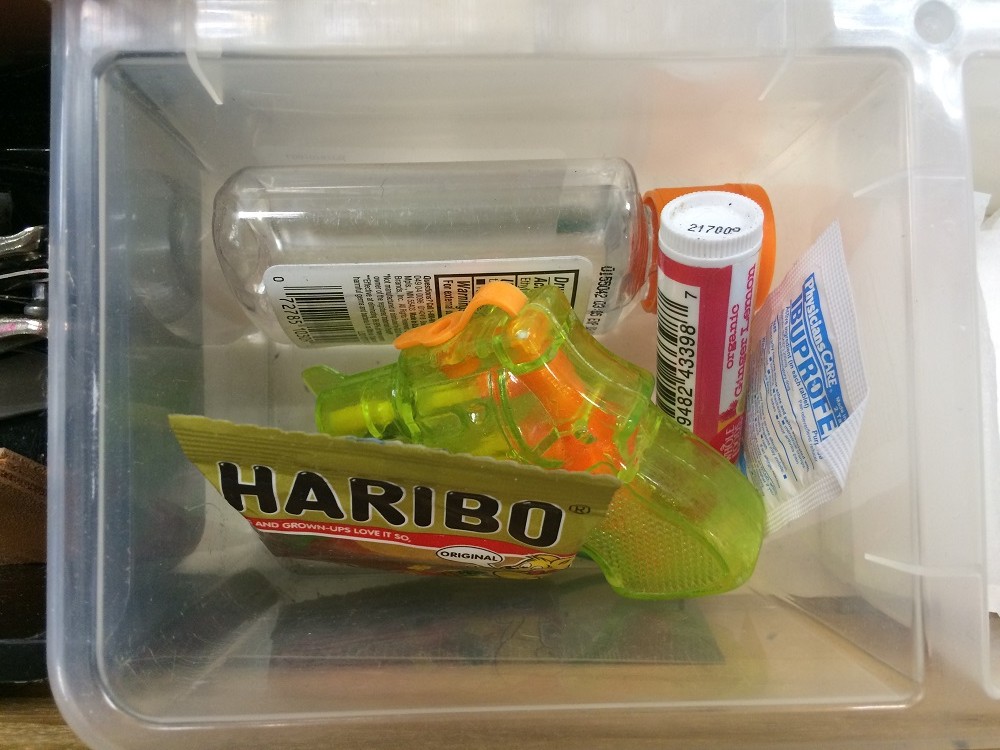

Sarah walked us through the overall benefits of having these repair materials on-hand – portability, speed, control – and the specific advantages of each adhesive. One of the greatest benefits is understanding the method of reactivation for each adhesive (this is also potentially one of the more challenging elements to remember, but luckily we walked away with an extremely handy chart). If media solubility is an issue, reactivating with water is likely not an option – in this case, one would opt to use a repair material that can be reactivated with either heat or a solvent. If the scope of a project is large but solubility is not an issue, it may be helpful to have a stash of water-activated repair material and a water brush on hand. If the object to be treated is parchment, gelatin- or isinglass-coated paper is likely a good option and for plastics or clear supports, synthetics may be the best bet.

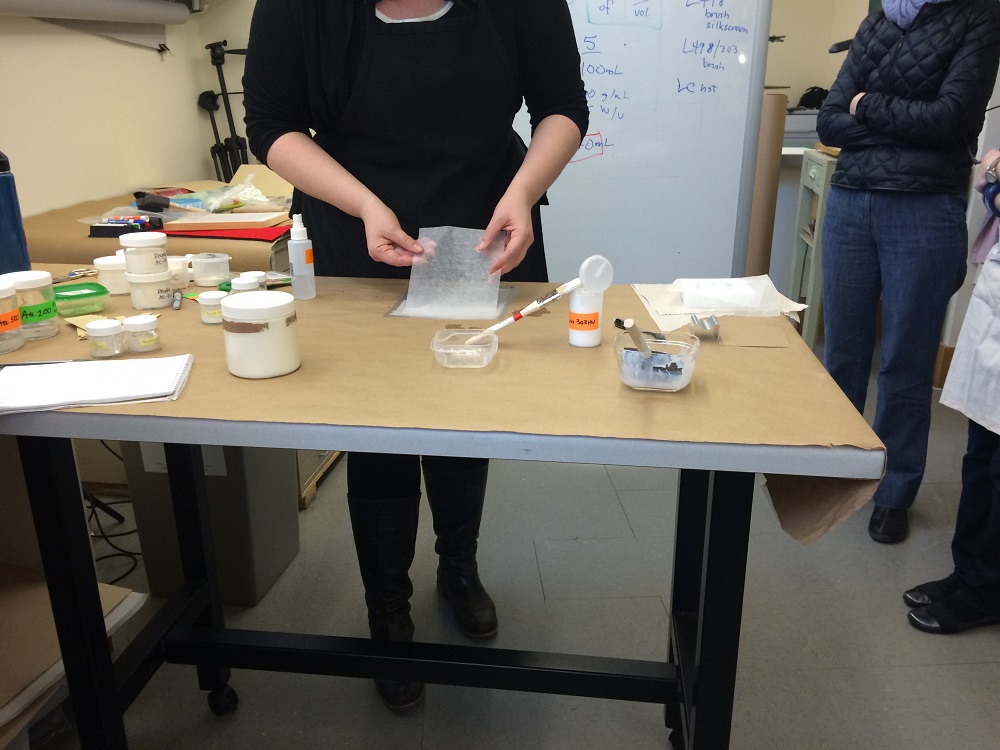

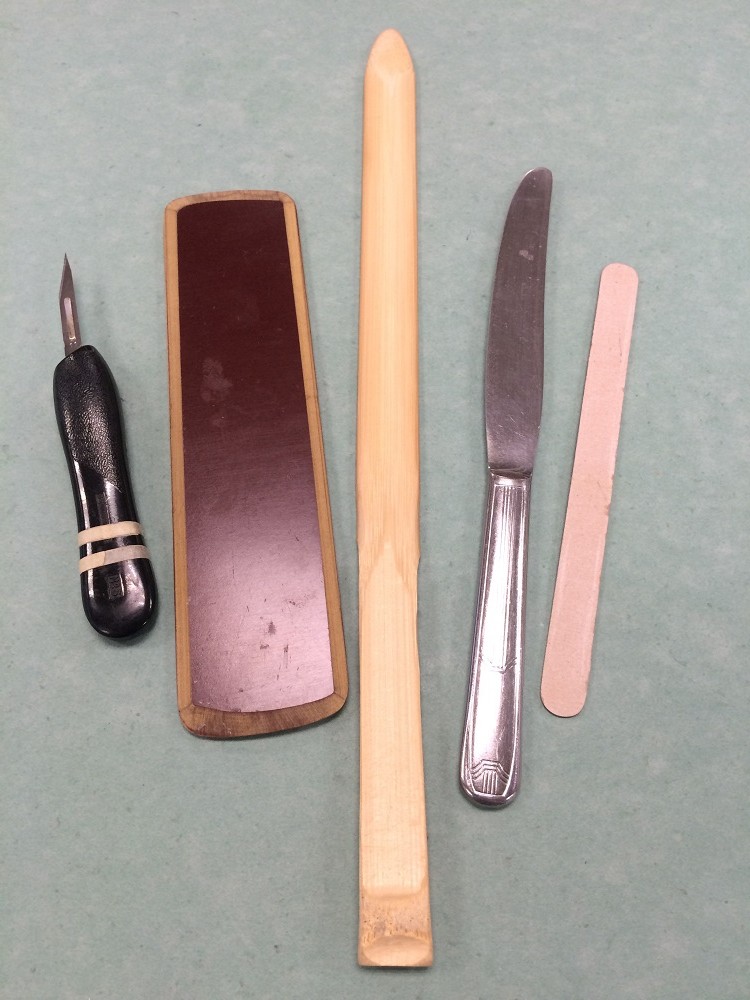

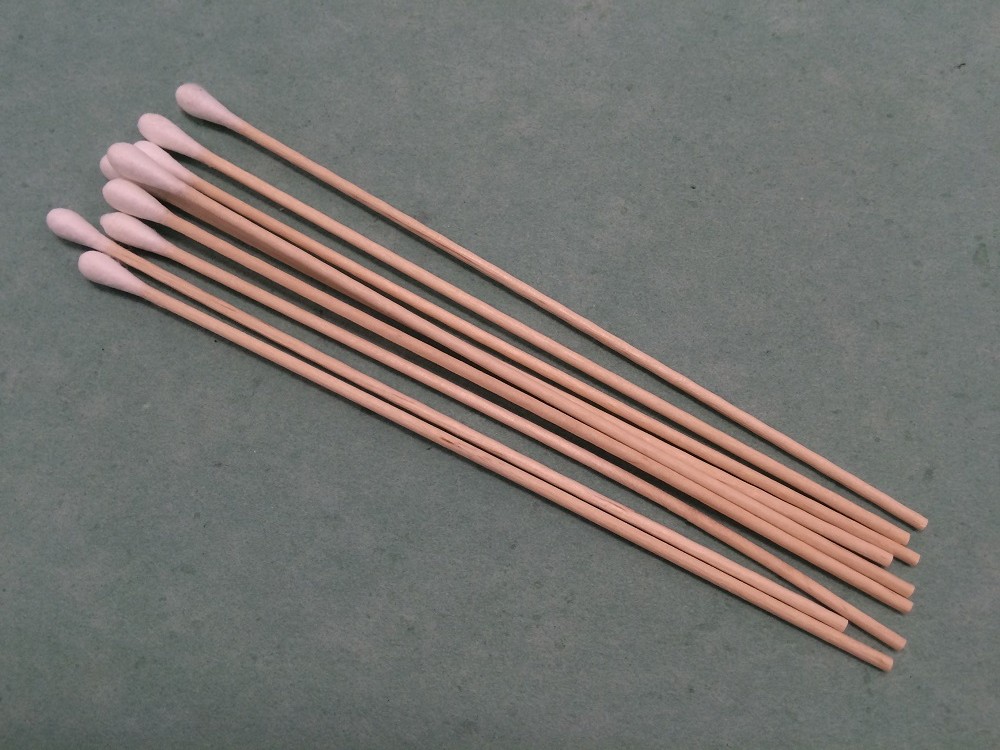

Pre-coated repair materials can be prepared with nearly any adhesive and paper that one has in their lab and can be done with several different approaches, depending on skill and comfort level. Many can be done with a quick hand and a piece of Mylar, while others utilize tools not always seen in a conservation lab – a bbq/oven mat, dough scraper, and/or a silkscreen.

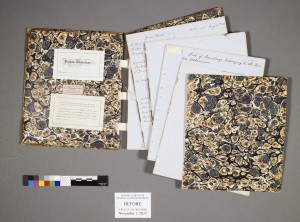

As with all conservation treatments, this is one that takes some time and experimentation to gain comfort with. That said, the risk and cost are very low. These materials can be toned to match an object and stored indefinitely. As they are controllable and customizable, they also offer a great advantage over commercially available products, whose formulations can often be unknown and can change without notice.

Sarah has taught this workshop several times now, both solo and partnered with Priscilla Anderson, Senior Preservation Library for Harvard Library, and it shows – she’s as organized as she is enthusiastic, which is saying something. Along with being extremely knowledgeable, she has a ton of great tips and sources for additional information, clever tools and other treatment ideas.

There’s a helpful bibliography of pre-coated repair information on Sarah’s website to get you started. Henry Hébert made brief mention of Sarah’s presentation of this technique in an earlier Flash of the Hand post and Mindell Dubansky, Preservation Librarian at the Metropolitan Museum of Art has a nice write-up on the workshop here. If you have the opportunity to take this workshop in the future, I highly recommend it – take-away soundbites like “gel and swell” and “first pancake syndrome” should be enough to entice you.

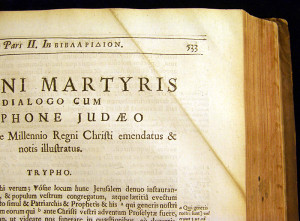

We were all curious to see how the book would dry, and how the paper would respond to a week long stint in the Motel 8 of wind tunnels. Continuing in this manner gave me time to consider and investigate the methods of washing, drying, and flattening that I had learned. And although it turns out that washing and drying intact is not actually faster, it is still just one more possibility.

We were all curious to see how the book would dry, and how the paper would respond to a week long stint in the Motel 8 of wind tunnels. Continuing in this manner gave me time to consider and investigate the methods of washing, drying, and flattening that I had learned. And although it turns out that washing and drying intact is not actually faster, it is still just one more possibility.

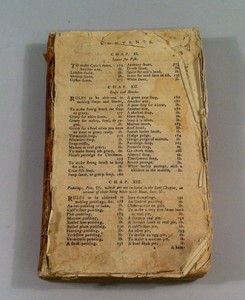

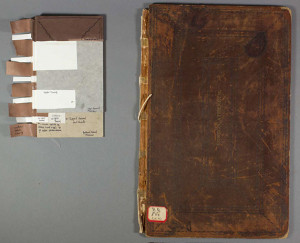

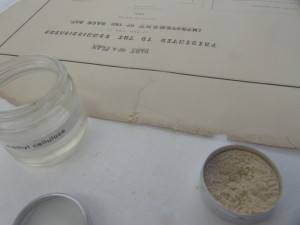

s, rubber eraser crumbs, cosmetic sponges, brushes… The list of implements goes on, but the concept remains singular. REMOVE LOOSE SURFACE DIRT. As you can see, one swipe of the sponge quickly leads to a hefty pile of spent latex, and one impressive jar of hair, dirt, dust, and many other unmentionables. [note: photographs are examples of three distinct pieces, and are adjacent for effect only.]

s, rubber eraser crumbs, cosmetic sponges, brushes… The list of implements goes on, but the concept remains singular. REMOVE LOOSE SURFACE DIRT. As you can see, one swipe of the sponge quickly leads to a hefty pile of spent latex, and one impressive jar of hair, dirt, dust, and many other unmentionables. [note: photographs are examples of three distinct pieces, and are adjacent for effect only.]

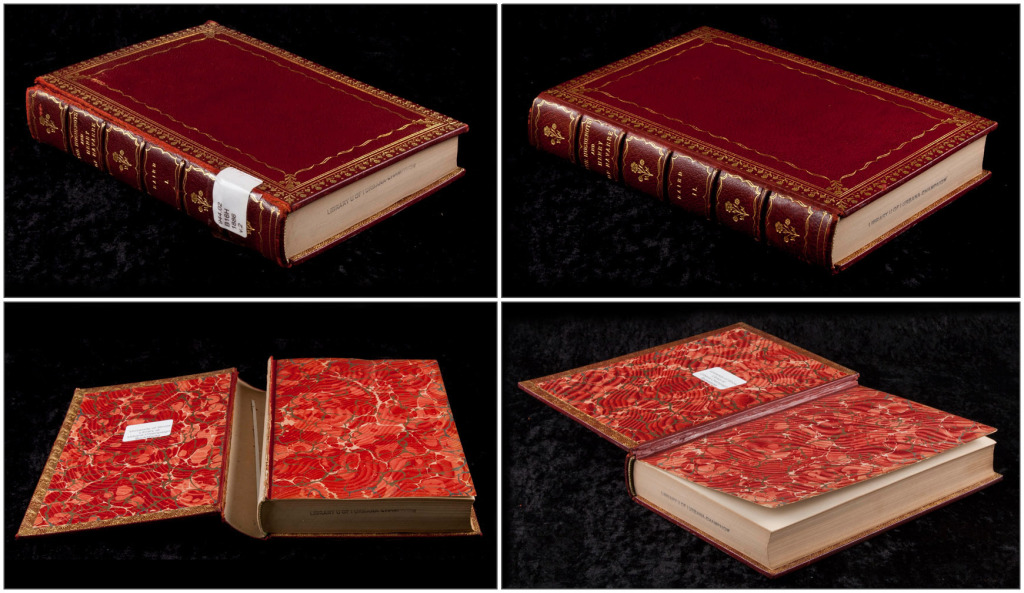

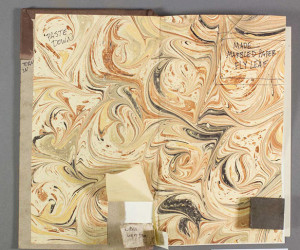

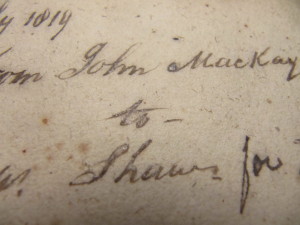

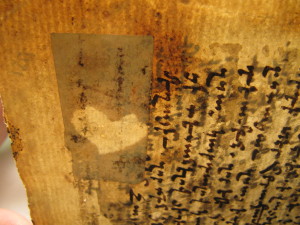

period of roughly 24 hours, the cyclododecane will sublime off the paper, leaving behind only the unaffected, unwashed ink. Then after washing, one is able to flatten and dry the paper between felts and weight. This particular fly-leaf not only lost any wrinkles or creases it previously had, but it brightened in color, added a degree of softness, and regained a sense of drape as well.

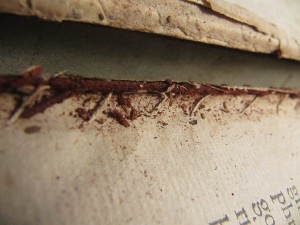

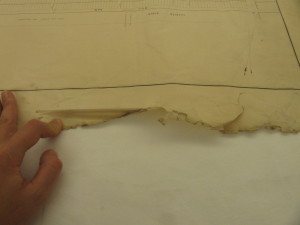

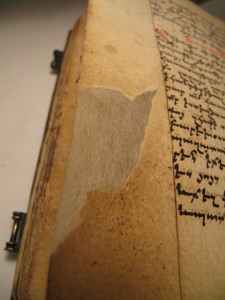

period of roughly 24 hours, the cyclododecane will sublime off the paper, leaving behind only the unaffected, unwashed ink. Then after washing, one is able to flatten and dry the paper between felts and weight. This particular fly-leaf not only lost any wrinkles or creases it previously had, but it brightened in color, added a degree of softness, and regained a sense of drape as well. of a blotter-reemay-weight sandwich, you will find the fold to have flattened out. I find wheat starch paste to be preferable to water because there is a bit of added control in the spread of moisture, and the paste adds just a dash of strength to the weakened area. [Note: tide-lines, and other horrible and unimaginable affects could be consequence to this treatment. ALWAYS spot test before introducing moisture into paper.]

of a blotter-reemay-weight sandwich, you will find the fold to have flattened out. I find wheat starch paste to be preferable to water because there is a bit of added control in the spread of moisture, and the paste adds just a dash of strength to the weakened area. [Note: tide-lines, and other horrible and unimaginable affects could be consequence to this treatment. ALWAYS spot test before introducing moisture into paper.]

you’ll have yourself an array of creams, whites and browns. This powder, being of the same “stuff” as your paper, will blend nicely when affixed with a small amount of paste or methyl cellulose. Sometimes, simply rubbing the fine powder across the mend is enough to discourage the eye from seeing the tear immediately.

you’ll have yourself an array of creams, whites and browns. This powder, being of the same “stuff” as your paper, will blend nicely when affixed with a small amount of paste or methyl cellulose. Sometimes, simply rubbing the fine powder across the mend is enough to discourage the eye from seeing the tear immediately.

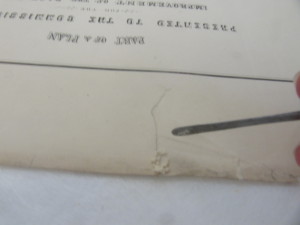

quickly, and only a little bit of weight is necessary. I like to turn the paper over, and add a second layer of the same tissue, overlapping the first mend every so slightly from the verso side. Here, it is good to paste up the entire piece, so that it sticks both to the paper being mended, and the first layer of tissue. A mixture of types of tissues and weights can and should be used to match the mend, the kind of paper being mended, taking into account the condition the original paper is in. Each repair is unique, and requires an arsenal of paste thicknesses (thin paste is more flexible than thick paste, but thick paste can be tackier) and different tissue types.

quickly, and only a little bit of weight is necessary. I like to turn the paper over, and add a second layer of the same tissue, overlapping the first mend every so slightly from the verso side. Here, it is good to paste up the entire piece, so that it sticks both to the paper being mended, and the first layer of tissue. A mixture of types of tissues and weights can and should be used to match the mend, the kind of paper being mended, taking into account the condition the original paper is in. Each repair is unique, and requires an arsenal of paste thicknesses (thin paste is more flexible than thick paste, but thick paste can be tackier) and different tissue types.