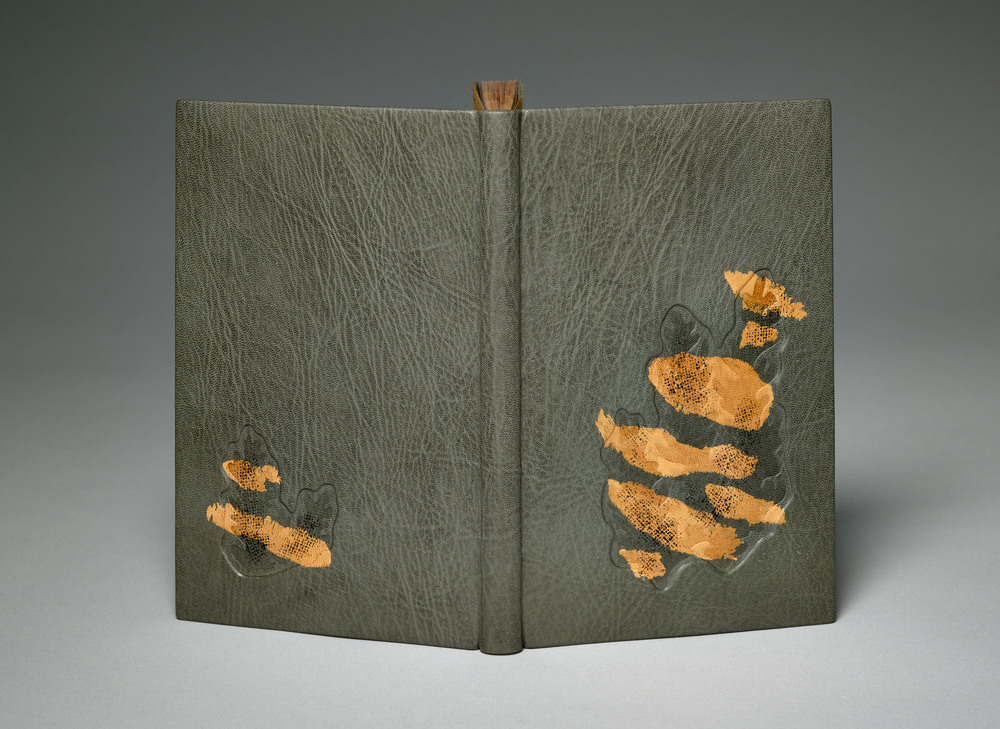

On a Calm Shore is a 1960 edition by Frances Cornford with illustrations by Christopher Cornford. In 2015, Kathy Abbott bound this copy in full grey goatskin with recessed and embossed onlays with relief printing. The edges are decorated and printed to match the design on the covers.

Can you walk us through the processes used to create the layered design in the recessed areas of the binding?

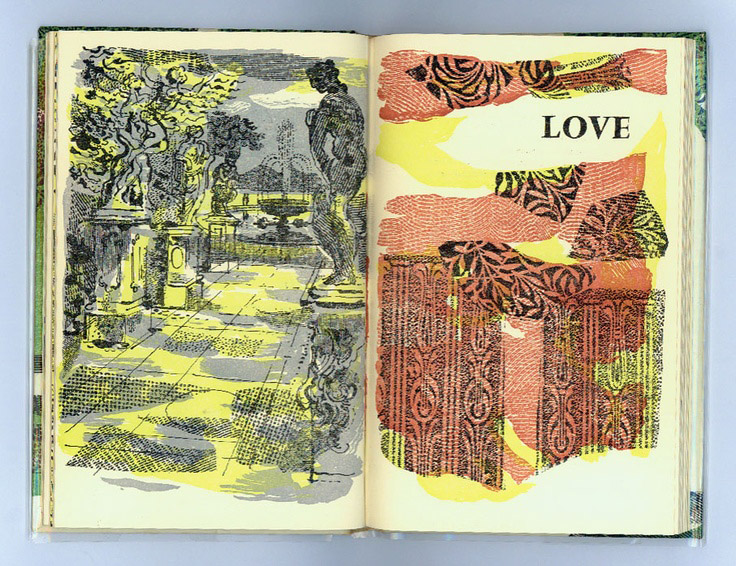

This text-block was a very unusual choice for me as it was printed in the 1960’s on modern paper and was heavily illustrated. I am usually drawn to early 20th century, letterpressed printed books from private presses, with no illustrations. When I found this text in a second-hand bookshop, I was delighted: the poems were charming and the illustrations were so vibrant and alive, that I just had to buy it.

I made this binding for an exhibition in London last year called: Covered. I have responded to the references to the sea in the poetry and to the layered screen-printed illustrations by the author’s son, Christopher Cornford on this binding. I felt that the structure had to be a fine binding over layered pasteboards so that I could sculpt the boards easily, and cover it in beautiful grainy leather, to create different textures.

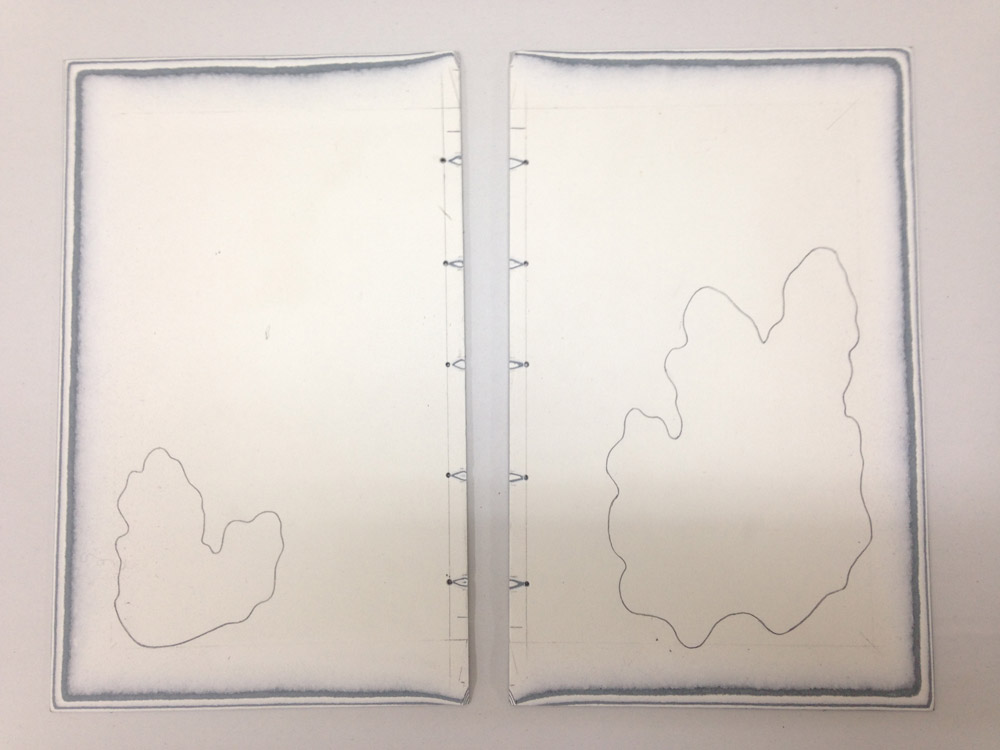

To create this design, I cut away parts of the boards; laced the boards on and lined the outside with paper to form a solid ground for the leather. I then covered the book with Nigerian goatskin, pushing the leather into the recesses with a very fine-pointed bone folder. I made seaweed-y shapes from millboard (a very laborious job achieved by cutting out the shapes with a scalpel and making bespoke sanding tools to get into the nooks and crannies) and then pressed the millboard pieces really hard into the dampened recessed areas of the covers. I applied the feathered yellow onlays, pressed the millboard shapes in again and then relief printed on top with acrylic ink through scrim, to achieve the texture, which is consistently used within the book’s illustrations.

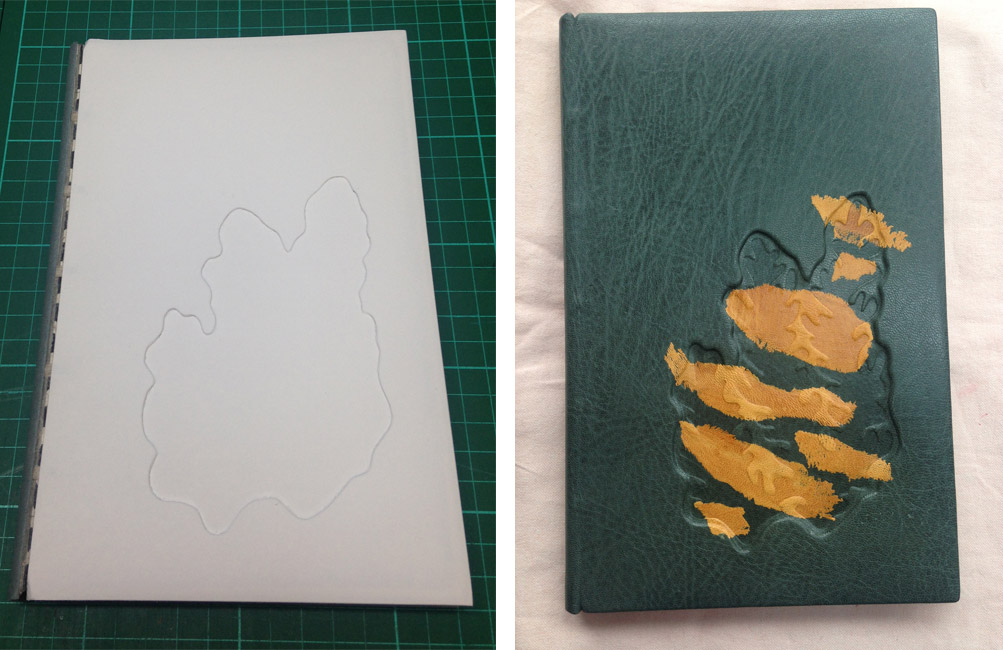

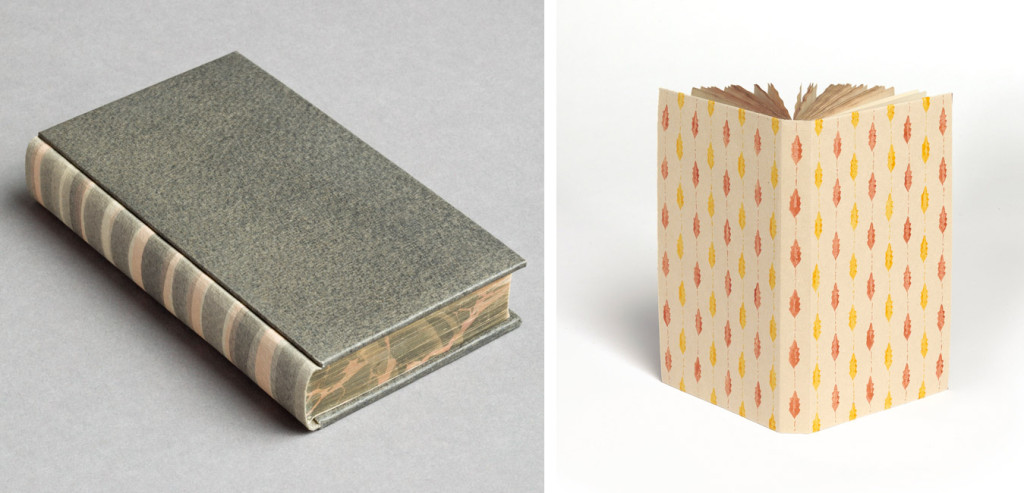

left: Boards laced onto book with design cut out | right: Binding covered in goatskin with feathered onlays.

My response to each book I bind dictates the technique I must employ, often pushing me outside anything I have ever tackled before, and forces me to be on the edge of my practice technically: I always embrace this process.

What techniques did you employ to carry that pattern onto the edge decoration?

I coloured the edges with terracotta coloured acrylic ink and then used the same relief printing technique for the texture.

This interview comes as a suggestion from Haein Song after I interviewed her back in February 2014. Not knowing anything about Kathy or her work, I soon discovered that, though her bindings may appear simplistic, her designs are meticulously planned and thoughtfully executed. In addition to her striking designs, I was pulled in by the gorgeous leathers used to cover her bindings. In the interview, I ask Kathy about her design processes, techniques and her strategy for choosing the perfect skin. She also goes into the concept behind Tomorrow’s Past and the ease of publishing a bookbinding manual.

Check out the interview after the jump for more about Kathy’s training and her creative process. Come back each Sunday during the month of December for more on Kathy’s work. You can subscribe to the blog to receive email reminders, so you never miss post.

What led you to study bookbinding?

I was 17 and due to begin a fine art course to ultimately, become a milliner: I have always loved making things. I decided to take a year out before the course and looked for art related jobs. I was sent some information about jobs within the printing industry and in a tiny paragraph, was a description of bookbinding. When I read that, I realized it was not a milliner I wanted to be, but a bookbinder, I just didn’t know that it existed.

A local bookbinding company then contacted me and offered me a sewing position with other ‘ladies’, but I wanted to be a complete bookbinder, which was only a man’s job at that particular company. I was tenacious and forced my way in, and I began a four-year apprenticeship there, working with 65 men: I was the only female. Bookbinding was my very first job and has been my only career path – I feel very fortunate that I discovered it so early on in my life.

Can you talk about how your different training experiences as an apprentice and then going through a program at a university helped to develop your skills as a binder?

They were very different. I was an apprentice at a trade bindery, where everything was mass-produced (though largely by hand). I went from having to make 50 leather cases an hour, to college, where we made one-off bindings of all types, to a high standard. The bench skills I learned as an apprentice were so useful but I was rough around the edges. College, and then university polished and honed my skills to a point where I was satisfied with my craftsmanship. I trained for 8 years in total to become a bookbinder.

How was the program at Roehampton University structured? What style of binding and techniques did you learn?

The bookbinding programme at Roehampton (led by Jen Lindsay) was like a Swiss finishing school for me, I learned so much there. The course was half theoretical and half practical. Our classes were: History of the book, Philosophy of Craft (why we make what we make and how we differ from other disciplines within the applied arts), History of book decoration, Design theory and then: Fine binding, gold tooling and Historical bookbinding structures. It was wonderful. Sadly, the course closed in 2001 as the university realized that they could fit triple the amount of drama students in the bindery space, – the room could only house a maximum of 12 bookbinding students. Education has become a business in the UK and now there are no full-time bookbinding courses here: it’s tragic.

In 2010, you published the bookbinding manual Bookbinding: A Step-By-Step Guide. I would love to have you talk about your motivation for writing a binding manual and what the publication process was like.

I kept being asked to recommend a bookbinding book by my beginner level students. I found it difficult to suggest one, as at that time, there weren’t many bookbinding books teaching solid foundational skills that were up to date. In 2009 a small independent publishers contacted me to see if I would be willing to write a bookbinding book. I’d written a lot of handouts over the years to support my teaching, and realised that they could be the foundations of a book.

The book took me about 9 months to write in my spare time and my husband (a graphic designer) designed the layout. I also had a brilliant photographer friend who took all the shots and Tracey Rowledge was a fantastic editor. The publication process was relatively easy going because of the people around me.

Do you have any tips or advice for someone who might be looking into publishing their own bookbinding related book?

I think it’s better to write a small amount per day than to try to sit down and write large swathes of text. Also, I found it really beneficial to note where I thought the text needed an illustration or photograph to illustrate a point. It made it easy to get the bindings prepared at different stages in readiness for photography and thus saved a lot of time.

In my interview with Tracey Rowledge earlier this year, I asked her about the formation of Tomorrow’s Past. Being that you are also a founding member of this group, I’d like to pose the same the question to you: Can you discuss the concern towards the modern binder’s attitude on design and structure when approaching an old book to rebind? What encouraged you to help form this group?

As Tracey said, Tomorrow’s Past was formed as a continuation of Sün Evrard’s campaign to consider re-binding antiquarian books (that no longer had a binding) in a style of the 21st century, rather than to go on making pastiche bindings (usually in the style of the late 19th and early 20th century). We are in danger of becoming invisible within the history of bookbinding (with the exception of contemporary fine binding, artists books and the like), as future historians will only be able to date us by our materials, not by the style and fashion of our time. Within Tomorrow’s Past, we are re-binding books using today’s knowledge, conservation practices and aesthetics but in a quiet way, without ego – straddling the world of book conservation, book art and bookbinding. And it is important to add, we are only trying to encourage people to think before acting and to offer an alternative approach to the re-binding of antiquarian books: it is not dogma. The needs of a book in our care should always come first, and that is something I feel very passionate about.

In addition to your work as a binder, you also teach classes. As a bookbinding instructor myself, I enjoy speaking with other binders about their reasons for teaching. What drew you to teach and what aspects of teaching do you find to be the most compelling?

Teaching is a very important part of who I am as a bookbinder: I just love it. I try to relay as much of my enthusiasm and passion for the subject as possible and I teach to a professional standard in a friendly and inclusive way, no matter what the level of the student is. I feel it is very important that students reach their full potential. I want people to be excited about our craft, as well as the materials and tools that we are so lucky to use.

Are there specific techniques or structures that you tend to teach?

I teach Advanced level Fine binding at the City Lit, London, UK, which is a 5.5hour class, one day per week for 25 weeks. We cover paper conservation, making pasteboards, leather-jointed endpapers, edge gilding/edge decoration, multi-coloured/threaded endbands, all other forwarding processes and then covering, inlays/onlays and other decorative techniques before putting in leather or paper doublures. It is a very intensive course.

I also teach some of the Tomorrow’s Past structures as well as more basic level bookbinding courses all over the UK and abroad.

this is great! glad you are doing it! Thanks!

T.