Recently, an album of letters came into the lab. Each letter, envelope and card had been adhered into a notebook, and had become brittle, creased, and difficult to handle. The notebook’s covers were both off, and its binding was in disrepair. Designing a thoughtful and safe treatment proposal for this piece will be complicated- the different aspects; historical, structural, economical, and intent of use will have to be weighed and balanced. To remove each piece of memorabilia will be difficult and time consuming, but would create the opportunity to mend and rehouse the pieces. However, a lighter touch is always better, and focusing on stability alone would preserve more of the original structure and composition. To treat this album well, it will be necessary to have an understanding of the current structure and adhesion, and the possible detriments these may cause; a consciousness of different potential structural solutions; and clear expectations for the future needs and use of the album and its contents.

Although I won’t be working on this treatment, the different concerns and possibilities associated with it piqued my curiosity. In researching different ways similar albums had been treated, I came across “A Photo Album Structure from Philadelphia, 1865” by Betsy Palmer Eldridge [Book and Paper Group Annual 21 (2002)]. It is an excellent description of a structure which, as Eldridge describes it, “can be used in the restoration of Victorian photo albums or in the construction of new stiff-leafed albums.” However, what I appreciated most about her article was the investigation and research her curiosity fueled. Although there were plenty of advertisements and descriptions about the albums, there were no detailed directions. Eldridge has constructed a method on how it is put together, and describes each step in her article. The best piece of advice I have yet been given is to pursue this curiosity- especially in the form of creating models. Working backwards, recreation, and developing ideas through writing are perhaps the best ways to fully know anything. This is especially true of books, who’s working action and composition is difficult to discern if fully intact. An historical model presents us with three-dimensional access to its structure and intended function, while also serving as an invaluable form of documentation.

While interning at the Wunsch Lab at MIT, Jana Dambrogio showed me a few models she had made of books she had studied. Not only did she replicate the binding structure, but all of the individual flaws and characteristics of the books as well. Each dog ear, tear, and hole was now documented in a book she could later handle and contemplate. This kind of work is an important lesson in patience, detail, and critical thinking. It slows the hand and creates time to ask questions. What am I trying to repair? What is the causation of the damages I am looking to reverse or minimize? Is every dog eared page an accident, or do they represent an historical figure’s notation? [Read about the Huntington Library’s famous fold here]

Not all dog ears are important notations, but every now and then there comes a crease I wouldn’t flatten

As a conservator, it is not my responsibility to lend gravity to an individual book; I must treat, and conserve each book with equal propriety, reverence, and respect. But it is my responsibility to stabilize a book for future use and understanding. By documenting what a book looked like before treatment I not only hold myself accountable for what I proceed to do with it, but I am also acknowledging its history and experience of time.

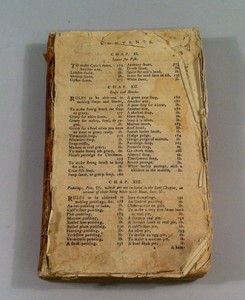

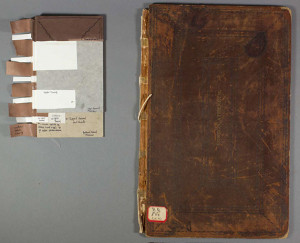

Documentation is our way of preserving as much of a book as possible, and creating a model of a working, physical manifestation of its history and experience not only aids researc hers and historians, but future conservators and bookbinders alike. I found this tactic to be especially useful when I was rebinding “The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy.” The front and back boards were missing, and the paper was torn and discolored. Imitating both the book and its defects forced me to mentally disbind and rebind the book before acting. I had to lend importance to each flaw in order to ascertain what the damage was, how it occurred, and what it could teach me about the structure and its experience.

hers and historians, but future conservators and bookbinders alike. I found this tactic to be especially useful when I was rebinding “The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy.” The front and back boards were missing, and the paper was torn and discolored. Imitating both the book and its defects forced me to mentally disbind and rebind the book before acting. I had to lend importance to each flaw in order to ascertain what the damage was, how it occurred, and what it could teach me about the structure and its experience.

First, I tried sewing the model all along, following the lines of an educated guess; but when I tried to mimic the tears and loose sections it became apparent that a different method had been employed. With trial and error, I was able to recreate the original sewing, finding explanations for most of its defects.  Once the book was rebound between new covers, its original functionality was restored, but it no longer told the story of its physical experience. Its history, however, is preserved in the form of photos, its treatment report, and of course, its model.

Once the book was rebound between new covers, its original functionality was restored, but it no longer told the story of its physical experience. Its history, however, is preserved in the form of photos, its treatment report, and of course, its model.

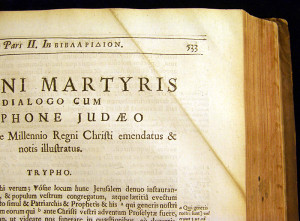

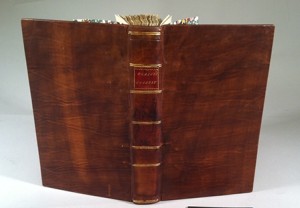

During the repair of a large book of tracts, disbinding was not a prudent option. I was faced once again, with a structure that was unfamiliar to me, and I found this made it difficult to decide upon a sympathetic treatment plan. The front board had come off, the paste down was lifting, and the spine piece was missing. The parchment slips were split at the point of hinging; half remained sewn along the spine, while the other half stuck out from between the board edge.

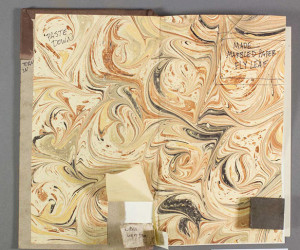

I was curious about the end papers and the board attachment. Remembering the advice Jana had given me, I made a replica of the cover, end sheets, and the first sewn section.

I spent all day trying to make sense of its many layers, and to discern where the attachment’s strengths and weaknesses were. By the end of the repair, I had not only reattached the board and reinforced its weak points, but I had learned a new type of binding as well.

In an interview posted by the American Museum of Natural History, Ichthyologist Scott Schaefer addresses the need to preserve the physicality of specimens:

Q: With a growing jurisdiction, since collections increase every year. Why is it still important to bring back physical specimens?

A: “Because they often represent the only tangible snapshot we have of life on Earth. You might say, “You can sample the genome of a specimen. You can take a photograph of a specimen, won’t that be sufficient?”

Well, the answer is no. It might be adequate. Those might be excellent photographs. That might be one kind of representation, if you talk about a genome sequence, for example. But it isn’t necessarily sufficient to answer all the types of questions that could potentially be asked about that biodiversity at that place and at that time…”

[Read the entire interview here]

Having information on a specimen will never be the same as having the specimen on hand. In order to get to all the nuances that Schaefer describes, to fully represent the snapshot of our bibliographic experience, it is necessary to have books, and to have original bindings. BUT as we conservators know, sometimes a book crumbles just by looking at it, and so we must compromise some originality for the sake of prosperity. When a book has aged beyond use, it is, I believe, best to gather as much information about it as possible, providing the greatest insight with the least amount of damage. And while I would prefer to be able to casually flip through everything in Special Collections, I won’t be the one to turn the stacks into a pile of red rot.

Original is best, (but I think Schafaer might agree) that when pressed, a clone comes in at a close second.