Action is often the focus of conservation literature and it is natural to discuss a treatment as a kind of narrative. Picture it: a cultural artifact, such as a book or painting, comes into a conservation lab in poor shape. The condition may be a result of poor materials, improper storage, or disaster, but the conservator, as protagonist and primary agent of change, intervenes to bring the object back to some ideal state. The story can be more routine, such as preparing objects for digitization, but it can also be kind of heroic, like salvage efforts following a disaster. Based on anecdotal evidence, it may appear that the conservator’s job is to quickly act in times of need.

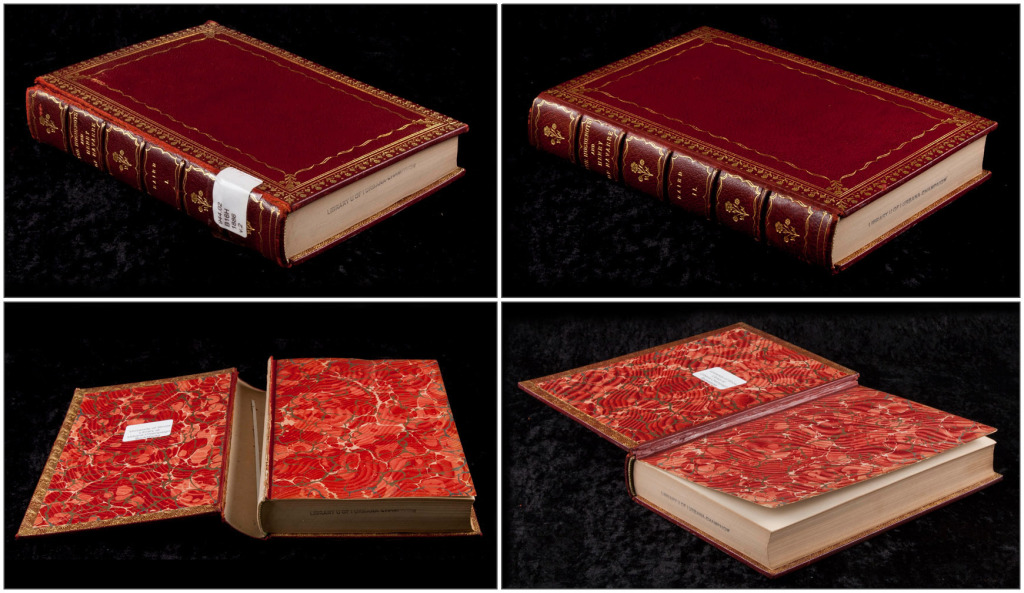

The images often presented as part of a treatment discussion corroborate this notion. Conservators take photographs of objects (like the ones below) before and after treatment as a component of documenting the work being carried out.

In my own experiences of presenting examples of conservation work to members of the public, I often show treatments that resulted in the most dramatic changes in appearance for obvious effect.

The initial urge to act when confronted with cultural objects in need can be both seductive and dangerous. Like one of those animal cruelty commercials with Sarah McLachlan singing in the background, a broken book makes me feel like I should do something. As a library conservator very early in my career, however, I often find myself questioning whether I should act at all.

Inappropriate treatment decisions can lead to irreparable loss of evidence or information. A characteristic of an object that may not be obvious to me or a curator, might be very important to a scholar in the future. And while I make every effort to ensure that my work is reversible, I must recognize that sometimes there is no going back. Of course, there are many factors to consider and each situation may be different. I often find myself looking back over the core documents of the AIC, namely the Code of Ethics and Guidelines for Practice, and at times come to the conclusion that the most appropriate thing to do is nothing at all.

The conservation professional performs within a continuum of care and will rarely be the last entrusted with the conservation of a cultural property. The conservation professional should only recommend or undertake treatment that is judged suitable to the preservation of the aesthetic, conceptual, and physical characteristics of the cultural property. When nonintervention best serves to promote the preservation of the cultural property, it may be appropriate to recommend that no treatment be performed.

I like to think about being part of the “conservation continuum” mentioned in the Guidelines for Practice – particularly in the context of previous repairs. At some point during a typical workday I’m often silently cursing some person from the past, who (with probably the best of intentions) executed the worst repair ever. In some cases, like these examples of stitching in medieval books, those repairs can be evidence of use and valuable to a researcher. More often in a research collection, however, the repair was done just a few decades ago by a library employee. For those that are damaging and particularly difficult to remove (like tape can be), I sometimes think that the object would have been better off if the shadowy perpetrator from the past had just left it alone completely!

The conservation professional must strive to select methods and materials that, to the best of current knowledge, do not adversely affect cultural property or its future examination, scientific investigation, treatment, or function.

– Item IV: Code of Ethics

Angry thoughts about my library forebears inevitably turn toward a role reversal, in which some future conservator is silently cursing me as they are reversing my work. As materials and techniques advance, we can only assume that some of our activities will be looked upon as barbaric or ham-handed eventually; however, making appropriate decisions based on analysis, research, and testing will keep this to a minimum.

The conservation professional shall practice within the limits of personal competence and education as well as within the limits of the available facilities.

– Item IV: Code of Ethics

In the end, if I’m not 1000% confident that I understand the materials in question and can complete the treatment myself with the tools at my disposal, I’m ethically bound to leave the item alone. I can look for someone else that is qualified to do the work correctly, or at least investigate other options, such as boxing or creating a facsimile, that are well within my grasp. Fortunately, many library materials can benefit from “benign neglect” in the proper storage environment and will not disappear without immediate action. While confronting the limits of one’s abilities can be hard, sometimes the best treatment option is to hold off until one of those future conservators comes along.