No one likes to think about all the little things (or, heaven forbid!, big things) that can go wrong as we work on our conservation projects. We are trained professionals. Our hands are steady. Our minds are sharp. And yet, as we work, any number of things could go wrong. A hand may slip as we lift adhered materials; a fragment may fall to the floor and crumble into a thousand irretrievable pieces. It’s sometimes intimidating to think about, but we all know in the back of our minds the myriad things that could go wrong.

This, of course, is why we take the preliminary photos so often considered as “simply routine.” With them, we preserve a record of what the book once was. Imperfect though they may be, photographic evidence is better than no evidence at all. But what if a photograph doesn’t show just what we were hoping?

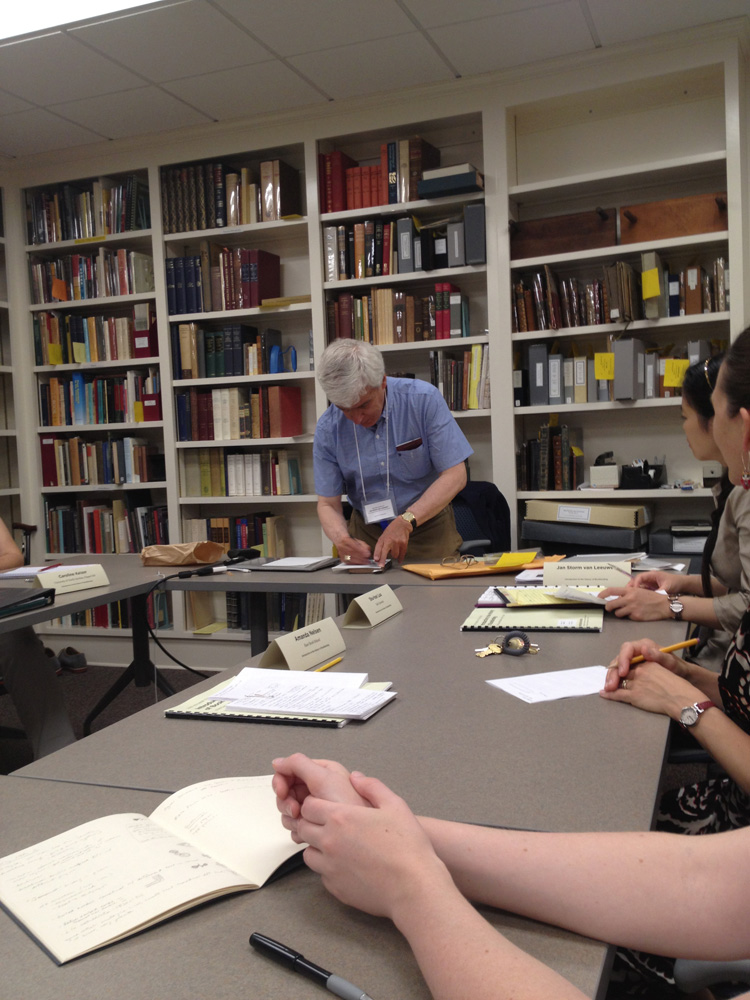

I recently had the opportunity to fulfill the role of the William Reese Fellow at Rare Book School in Charlottesville, VA. The fellowship provided a week of class for a week of service to RBS. In my case, specifically, I acted as an on-site conservator for some of their most in-need collections. The class I took was Jan Storm Van Leeuwen’s “Introduction to the History of Bookbinding,” which coincidentally was the same class attended by Erin Fletcher, the proprietor of this blog. The conservation projects were wide and varied, as RBS’s large collection is intended for teaching students of the book with countless focuses and interests.

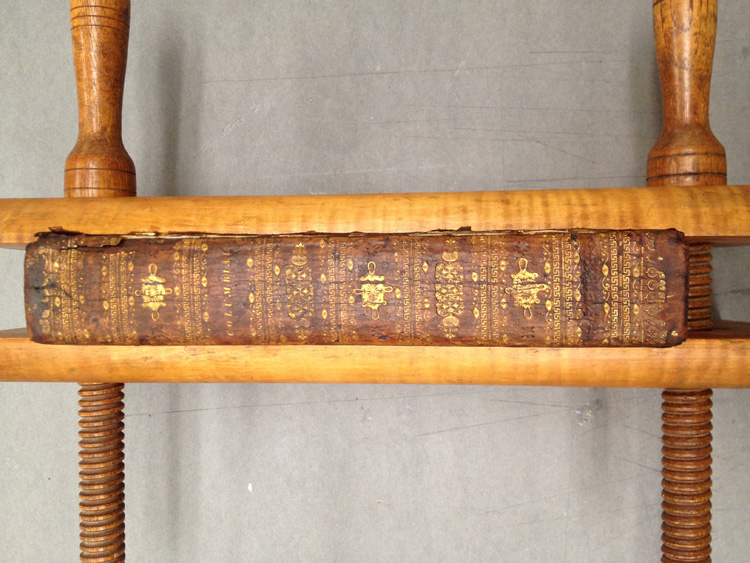

One of the books I was presented with was a first edition of Joel Barlow’s The Columbiad—A Poem. Of course, RBS valued this copy not only for its edition, but for its binding. The binding was original; in full calf, decorated in gold and blind tooling, it was an exquisite example of early American deluxe binding.

The upper board was entirely detached, and the bottom was in imminent danger of becoming so. The tight back spine was cracked and suffered redrot, and it was evident that a leather reback was necessary to preserve the book’s utility to the school. The danger of this treatment, of course, is that, should anything go wrong with lifting the spine, its beautiful panel tooling might be lost.

I photographed the book before commencing work, documenting individual tools as well as the overall patterns in which they were used, and then I began.

First, of course, was consolidating with redrot cocktail, a combination of SC6000 and Klucel G. This in and of itself revealed a new element to the book. With the darkened leather characteristic of redrot cocktail, blind tooling was revealed on the spine where originally it had appeared as an empty intermediary panel. I re-photographed the spine to document this tool, but it was difficult to make out even with a naked eye, let alone through the lens of my camera.

I then realized I could make use of one of the techniques taught to me in Van Leeuwen’s class. This is something Van Leeuwen made use of frequently in his time as Keeper of the Book at the Dutch Royal Library in the Hague, and which I now hope to employ more regularly in my documentation. In short, he took rubbings of the decorative covers of the library’s books.

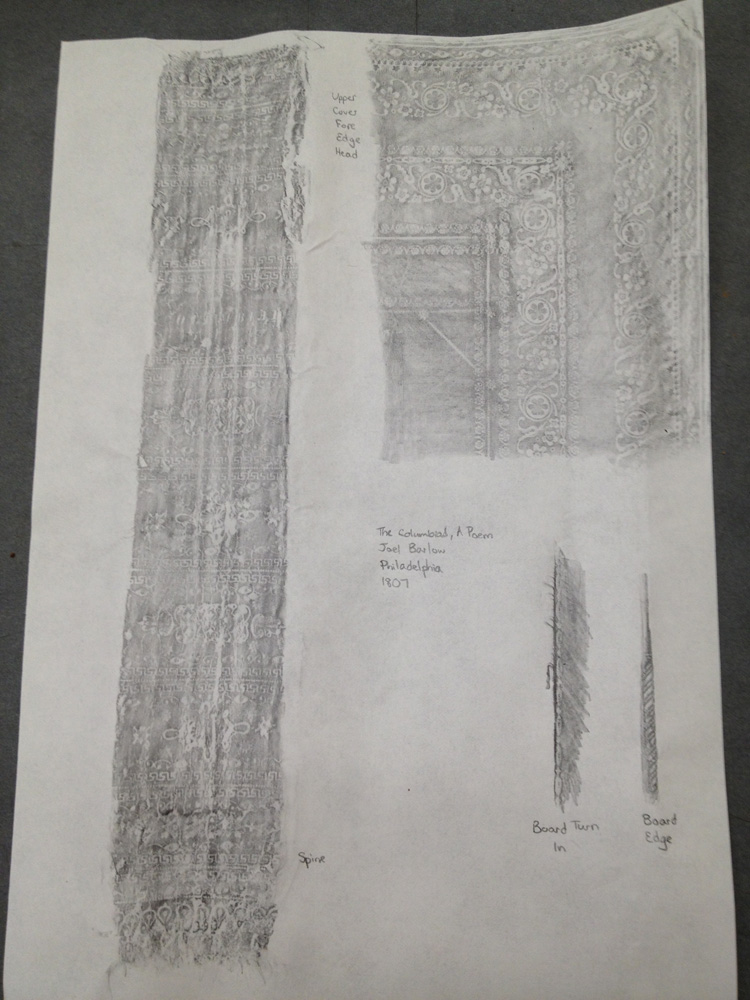

Van Leeuwen uses an artist’s soft graphite pencil and a light wove paper he commissioned specially for the practice. He lays the paper over the area to be documented, plants one hand firmly to keep the assembly in place, and begins his work. Holding the pencil at a nearly 45 degree angle, he rubs gently horizontally, vertically, and to every angle. He changes the angle of the pencil as he works to capture the specific aspects he wishes to be revealed in the tooling, sometimes circling the pencil, sometimes pressing harder or softer. Varied depths and lacework lines reveal themselves in great detail as he works, rendering a copy in shades of black and white of the book’s decoration. Van Leeuwen takes care to note the book being documented, to what portions of the book each image belongs, as well as the date and the taker of the rubbing to provide a good record for researchers.

It was with great excitement that I was able to use this technique in a real-life situation so shortly after having learned it. I experimented with various tissues intended for repair. Their soft texture and flexibility offered a good medium for capturing the imagery of the tooling that the camera would not. It took several trials to find a suitable paper that would provide the suppleness to sink into the tooling, yet not tear with the use of the graphite pencil, but once the proper paper was found and the rubbing taken, the image of the tool was revealed in greater detail even than could be seen simply by the eye. A satisfying result indeed!

Having taken the rubbing, I faced the spine with solvent set tissue, lifted it in one solid piece, performed the reback, readhered it, and once again removed the tissue. In all, the added precautions of taking the rubbing were not strictly necessary, but it was a reassuring way to expiate the danger of losing this piece of early American tooling in its entirety.