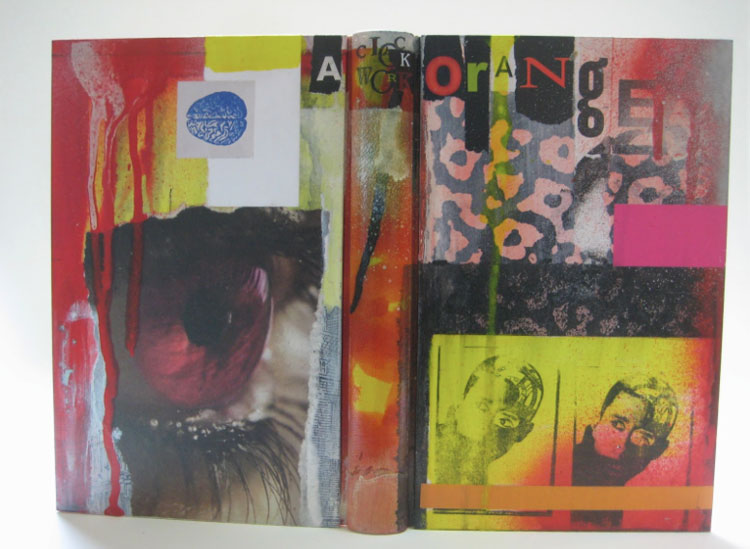

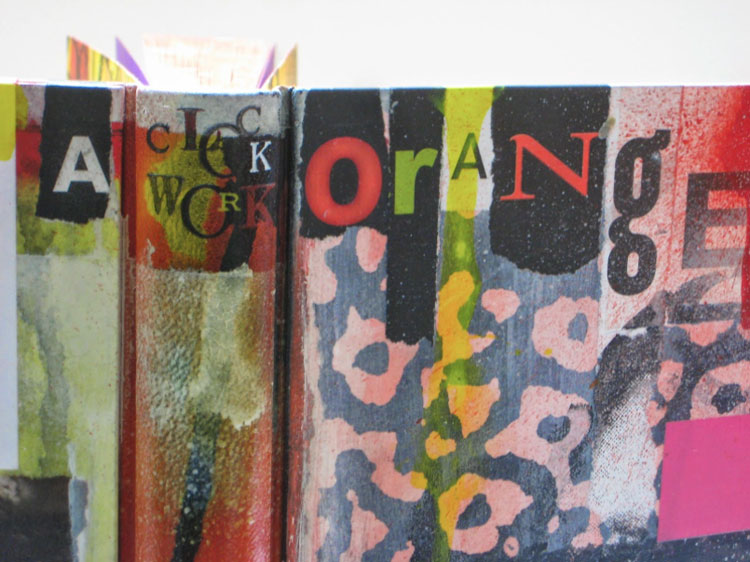

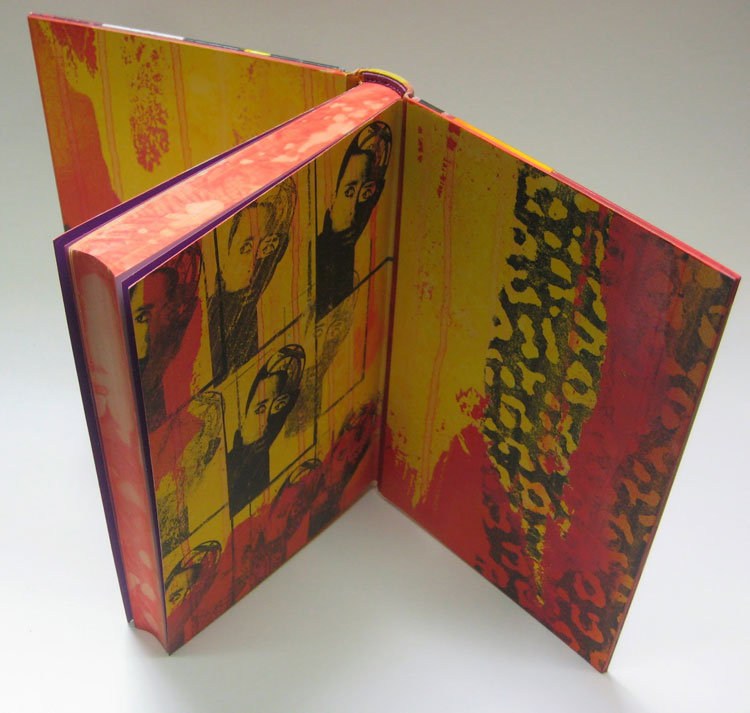

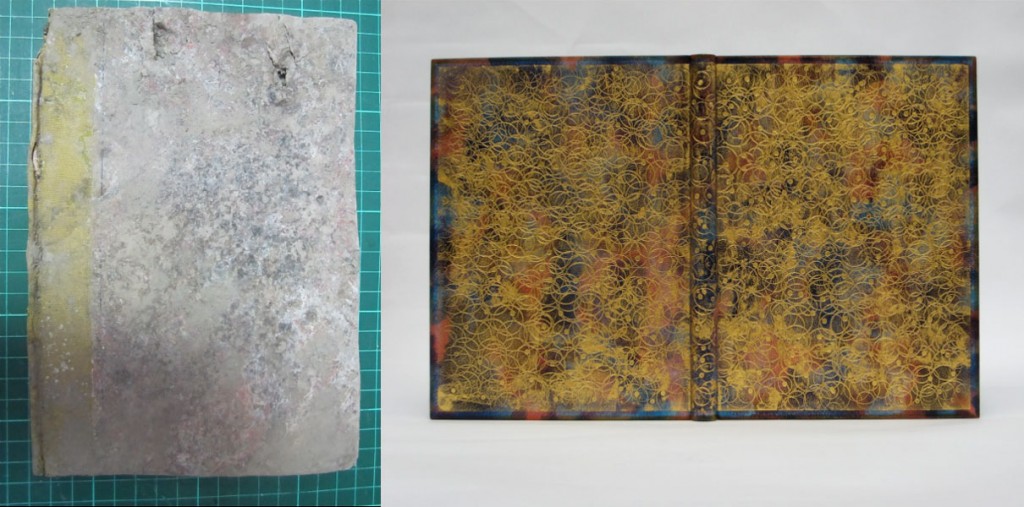

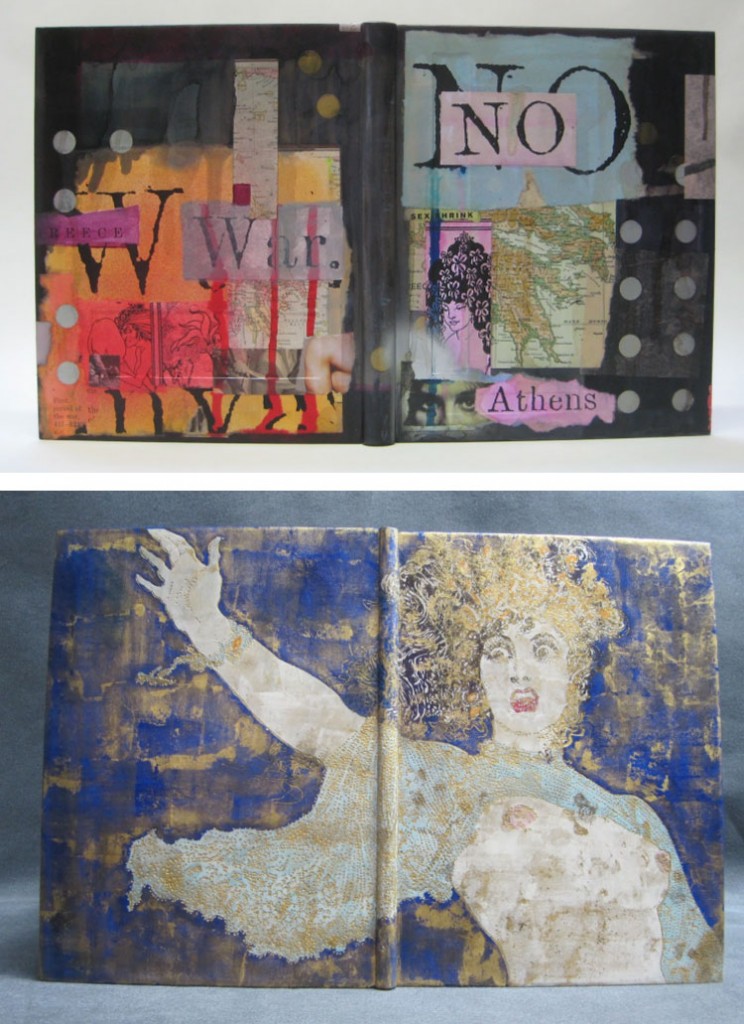

This binding of A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess was recently completed by the imitable Mark Cockram. The design is free of constraints, running wild and pushing the boundaries of the typical composition found on bindings past or present.

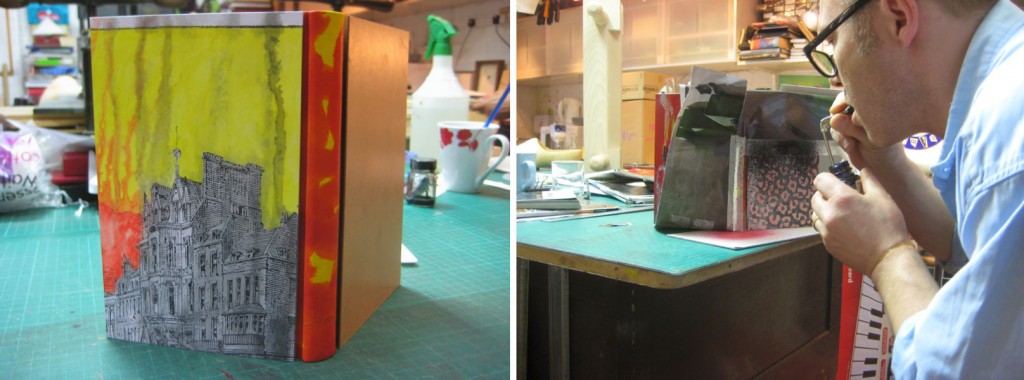

Below are just two of the many photographs that Mark has shared on his blog documenting the progression of the binding. You can find more posts here. Seeing the transformation of the covers offers an even greater appreciation for the binding, exploring the work and dedication that was put into it.

A Clockwork Orange is special to Mark and deserved the right style of binding and design to speak of its story appropriately. The book is a second edition with a tipped in plate signed by the author.

Your bindings have begun to develop into more textural surfaces with complex layers of color and graphics. What made you feel ready as an artist and bookbinder to bind a copy of this iconic title?

I think I have always been interested in mixed media, even at art college my tutors would run out of things to say about my work. I suppose that with all the combinations of materials that have been and are being used to make books and how artists use materials, there is nothing new about what I do. I went to college in an age before the computer and for me cut and paste is just that… cut and paste.

One aspect of bookbinding is to learn the skills that we need to make a book. This can be a life long journey. Some get so wound up in the technique and the craft of making that they forget the art of making and how design and art are as important as craft. I feel there has to be a balance in all things. Worse are the binders who say they work in the contemporary. Binding each book that finds itself on their bench with the same technique and material manipulation year in year out. The only apparent difference being the colour and the title.

I realise that binders like to sell their work and it is so tempting to go for the easy option, after years of training and developing their ‘signature binding style’ and then the work begins to sell, it is at that time that forward movement ends. The collectors become comfortable with the styles of these binders. I have heard collectors say, at more than one private view “I have to have a so and so binding, I do not have one of his/hers yet”. It would appear that they are not collecting books, but binders work… Most binders working in this field tend to work with private press books from the 1890’s + (Golden Cockerel and the like) or modern private presses. I know that some text blocks are beautifully printed, but most titles and themes just seem to be dated. So who is to blame? The binders for doing the same thing year in year out? Or the collector, buying the same thing year in, year out? Or is it something else? Like a combination of the two.

I prefer to move forward, to work with each book separately. To use an existing technique or to find something different depends on what the book needs. I do revisit past styles or working techniques if suitable … not as a matter of course. Over the last year or so I have been working with more mixed media. I suppose it looks like I go through phases with my work, but I tend to collect a few books that I feel a particular way of working would lend itself to and go for it.

A Clockwork Orange is one of about 3 or 4 books that have a very graphic, layered, multi media feel and look to them. What else could I do with Clockwork? A full leather binding, generic traditional gold tooling with a nice label to the spine, 5 raised bands, marbled paper endpapers? Hardly contemporary and hardly in keeping with the text I think. It has been said that I am a brave binder, to take risks, to do what is not expected. I could take the safe path, bind in a fashion I know would sell, with the least amount of thought. But in reality I could not call myself a designer bookbinder let alone a contemporary bookbinder if I were to do that and most important I would not be either honest with my work and the book.

– – – – – – – – – – –

While a student at North Bennet Street School, I had the opportunity to travel with my fellow classmates to London. On this trip we spent an afternoon at Studio 5, Mark’s bindery space. His energy was infectious as he bounced around the room demonstrating various techniques and answering all of our eagerly asked questions. I regrettably did not take the time to get to know Mark further that day, so I was very happy that he agreed to be interviewed on my blog. I am in constant awe of the work he churns out, both in their execution and design.

I’m so delighted to present the following interview with Mark Cockram. His bindings transform the traditional view of bookbinding and push the form into a new level of design. His work and dedication to the craft is aspirational and Mark has thoughtfully answered each of my questions with so much passion and truthfulness (with a bit of wit mixed in). Throughout the month of August, I’ll be presenting a binding of Mark’s each Sunday.

Enjoy the interview after the jump.

So it’s always good to start from the beginning. When did your interest in bookbinding begin and how have you studied the craft?

There is nothing either more dangerous or creative than a very young child with a book in front of them and two handfuls of crayons. Perhaps it is the notion of colouring in or adding too, that delights the child in us all. I was lucky, my parents neither discouraged or encouraged me in this creative pursuit. Later this book artist or altering the book trait was encouraged. Like many school children in the UK, we had to cover our text books in the wallpaper at the end of the roll or in my case (as we did not have wallpaper) small pieces of brown wrapping paper glued along the edges to make a big sheet. Over the educational year these covers would become personalised, the occasional ‘teacher check’ would result in areas being censored thus creating a patchwork effect that I remember with fondness. These creative covers would then be discarded by the next wave of eager scholars.

I realise that covering a book in paper is not bookbinding but it is the first recollection I have, along with the crayons, of working with the book.

My family has an antiquarian book business, The Harlequin Gallery in Lincoln. So books were always part of my life, thus it was perfectly natural for me, on leaving school to become an archaeologist. It all sounds very grand, but I was basically employed as a human earthmover. After 2 digs I decided to take a short break on Crete (for the archaeology) and ended up living there for some time, spending days and evenings with some rather bohemian artist types, painting and having a good time. It was then, in my naivety, that I decided that I too would become an artist and on my return to the UK enrolled at Lincolnshire College of Art and Design.

Upon graduation I began my career as a freelance artist. From pavements to galleries, from Lincoln to London and finally Paris in 1988 where I rediscovered the book. It was a wet Wednesday evening and I was walking to my digs when the Parisian heavens opened (it was summer) I dodged into a public building. As it happened the building was an annexe of the Bibliotheca National, I had stumbled into an exhibition of part of their collection, via the exit. Going against the stream (I feel that I have always done that) and numerous Gallic shrugs, I viewed the exhibition. From Gilbert and George through to Books of Hours. I felt comfortable, at home. I understood. I then decided to do the exhibition the correct way, from Books of Hours through to Gilbert and George. I still felt comfortable, equally at home. I still understood. I left wanting to be part of this world.

I returned to Lincoln and studied as a part time student on the bookbinding module of the conservation course at Lincolnshire College of Art. This was short lived as the module closed halfway through the second term. I did not realise at the time, but this closure was the start of the closures of nearly all the bookbinding modules and courses in the UK, for me at that time though, it was probably the deciding factor to take the plunge. I looked at full time courses and happened on a course in a Technical College in Guildford. I liked the sound of it, called and arranged an interview.

I was met by the head of department, a certain Maureen Duke. Looking back I am surprised Maureen let me into her office. I had hitched down and looked as if I had. I sported a Royal Signals, bright red band jacket, a bent Trilby and dubious jeans. I do not recall much of the interview, nerves I guess. What I do remember though was Maureen’s straight forward manner. When she asked to see recent work I handed over a small, brown, cardboard suitcase. As she looked at my half finished books she asked “Do you know or have favourite bookbinders ?” Gilbert and George I ventured…… She then asked if my friends and family thought I was strange, I replied “My friends and family, no” The next thing was Maureen introducing me to the then first years, in a voice that any drill instructor would be proud of “Friends, this is Mark, he will be joining us next year”. Interview over, I hitched back to Lincoln realising that I had much further to go.

The next two or so years were frantic. Lessons started at 9am but we were usually in the class by 8am and worked through until 8pm or so in the evening, five days a week. At the weekends and some nights I worked in a kitchen to pay my way, but always the book came first. Our teachers shared our passion, Maureen Duke, Maggie Chandler, Bob Shrigley, John Mitchell, with relentless technical support from Roger Callow. In many ways the dream team of tutors. Writing this brings to mind so many thoughts and memories, too many to mention as they all clamour to be heard and perhaps one day will. Such was the reputation of the course that graduates were almost guaranteed of a position if they wanted one, so I naturally opened my own place in Lincoln. That is when the real learning started. I often heard that one of the best ways to learn is to teach, I never thought I would have the skills or the guts to teach but as my confidence grew I began to give lectures and workshops. I think my first student in Lincoln was a Mr. Gavin Dovey. I hear that he is doing rather well now. I later studied under Atsushi ITO at Studio Livre in Tokyo and the bookarts course at the then London College of Printing. I still consider myself a student, I am constantly learning, always finding out new things, new skills and new ways to improve both my work and myself.

Your talents extend beyond bookbinding and into a range of other mediums. Many of your bindings display harmonious relationships between printmaking, painting and bookbinding techniques. Are you educated in other artistic mediums or have you used bookbinding as a means to experiment with new techniques?

I do not let the notion of what a bookbinder is perceived to be and expected to produce get in the way of my work. I studied art before books so I always come to the book with art and craft in my mind. For me there cannot be one without the other. The education I received at Guildford and elsewhere in bookbinding was/is important as it laid down the foundations of good working practise and the importance of good construction and materials. Also, because I teach and have students in the studio whilst working I have to be able to explain why and how I do things, I have nowhere to hide, my work has to stand alone. For example, my Kinsugi Binding is sculpture. I made the book, it was my sketch book until I filled it. I was buried and further manipulated into what we see today. To counter this my Water binding is full goatskin (hand dyed) with gold tooling, edge to edge doublers, a very traditional binding style. This then begs the question, am I a book artist? or a book sculptor? bookbinder? am I all or none? Mel Gooding describes me as an artistic bookbinder, perhaps that is the answer. There has to be a balance in all things we do. Though the skills, some of the techniques and materials I use when making a book are traditional, I recognise that I work in the here and now.

Your bindings evoke so much energy between the textural layers and graphics, being amplified by striking color palettes. The creative process is documented and presented on your blog, which is quite engaging. Is each step of the decoration meticulously planned out or are you experimenting spontaneously on the book?

Each book is different, therefore I try to start each project fresh. If the work is a commission then I do tend to produce a design (as in the case of both of the Lysistrata bindings I have done) I work out the construction details and the design concept at the same time. A design can take a few minutes to work out whilst the construction can take weeks, making scale models to make sure all is right and the balance works. On the other hand the opposite can happen. I am lucky to have students with me as working in isolation can be so deadening. I enjoy working in a creative atmosphere, ideas spark off each other. I also look outside of bookbinding to find answers, I view other artists work, their working practises, why they produce and what they produce. I often go to book exhibitions and leave disappointed, the same work by the same binders. I like to keep my work fresh, to look forward. This does not mean that I do not revisit a construction or decorative technique, I do, but only if it is applicable. I practise before I use a new method, so what may appear to be experimenting spontaneously is more of a controlled, spontaneous experiment.

Beyond your design bindings you also create elaborate and complex artist books. You’ve continuously played with the ‘buried book’ by laying bindings in various soils for different durations. Can you talk about this project, your concept and inspiration? How have the results varied depending on its location around the world?

The concept of the book in itself is sometimes beyond me. This everyday object that is so universal, is a thing of wonder. For a moment, let us imagine that there are no books, never have been, where does one start? The book is so multi-faceted being in constant development for more than 2000 years that to pinpoint a beginning is impossible. Different cultures spanning the world and time have their own form of the book. The social-economic impact of the book is still reverberating around the world, once what was revered and cherished has now become the throw away.

Being a bookbinder, I work and live with the book so it may come as surprise to some people that I also bury my own sketch books to see what happens. I suppose it began with the festival of the insect… Pestival. I knew the organiser and creator of the event and she asked me if I had any books with silver fish and other insect damage to exhibit. I said I had and for the first Pestival insect damaged books and other books to do with insects were exhibited.

Things moved on from there. In many cultures it is forbidden to destroy any book and one way to off load unwanted books is to bury them (hence the Dead Sea Scrolls). In that way nature deals with the problem. As I pondered this I began to look at the book and all of the different components that go into the making of books from the earliest times to the present day. All the materials in books (until recently) are derived from nature. The reason insects lay their eggs in books is because the books are nature, albeit manipulated by humans.

For the second Pestival at the South Bank Centre on the south bank of the Thames I decided to return one of my books back to nature, to bury it and document the results. I had managed to contact Amoret Whittaker, a forensic entomologist at the Natural History Museum and we also worked on controlled experiments. The results were amazing. All the details and the film can be found on my blog site. I just carried on from there, with books being buried by students from abroad or when I was abroad teaching or exhibiting. So much depends on the soil type, weather, time of year and depth. All I can say is that when you see a movie and the characters have unearthed a book hundreds of years old it will look nothing like they show it.

One of my favourite buried books went all the way to Thailand. It was buried for 4 weeks. The book when it arrived back in the studio was an eye opener. As it dried out it began to twist and contort. The pages had fused together and the boards began to crack. Eventually, after the movement ceased and it had dried out I began to repair it with a technique borrowed for Japanese ceramic repair, Kinsugi. Again, a short visit to my blog may shed some light on this. It is beautiful.

I have been criticised by some of my peers for destroying books, but I feel that if I make the book then it is my choice as to what I decide. Though it gets easier over time, I still find it difficult to let nature take control. However I realise I cannot fight nature, so I make use of her.

Recently, you collaborated with poet Roger McGough and students to create a project for the 800th birthday of Liverpool. This unusual book arts exhibit took the work out of the book and onto a series of doors. Can you discuss the concept of using doors as the platform and how the work connects to the book?

The Liverpool Doors project started off as as simple conversation over a couple of pints in our local pub. I have an eclectic mix of friends, artists, creatives, authors, art critics, curators and the like. I am very lucky with my friends and Roger McGough is amongst this number. Roger is a very well known poet, playwright, radio show host and much more and is often invited to put his poetry in public buildings and spaces. The New Museum of Liverpool was opening and as Roger is a son of the city he was commissioned to create work for a 6 month installation.

Quite often we will talk about our projects or show recent work, it is so refreshing to get feedback and insights from non bookbinders. During one of these chats Roger told me about this commission and asked me for my thoughts. Coming from a bookish back ground, I suggested that his work could be in big books. “How big?” … I am not sure how doors came into the conversation, but the idea stuck. I thought of them as huge diptychs, we then talked about what is found on doors. House numbers, house names. Notes pinned to them for the milk man. So much. Who has been through doors, open to new worlds, journeys… birth, death and all in between.

Liverpool was going through a huge rejuvenation at the time, doors were to be found lining skips or barricades to building sites. We could save these doors, part of the cultural heritage of Liverpool from the tip, involve students from the Liverpool John Moores University (Arts) …. we had our medium. The New Museum of Liverpool were very keen on the idea and work began. We went on local radio, TV and the newspapers got hold of the idea… we had doors donated by both Everton and Liverpool football teams. The Everyman Theatre (just before it was pulled down). Family homes and important buildings suddenly had no doors.

What started as a project that was a few words turned out to be a community event. The installation was the first of its kind in the second phase of the opening of the New Museum of Liverpool. It had been intended for the work to be shown for 6 months, however, it lasted for a year and a half and elements of it now form the core of the permanent collection of the museum. Since then we have gone on to Dubai to do a similar thing.

Studio 5 was established in 2003 as both your workspace and a teaching space. You’ve aided in the development of some talented bookbinders such as Gavin Dovey and Haein Song. Are you offering both workshops and private tutoring?

Education. This is where I stick my neck out and will probably commit professional suicide.

Education is something that I am passionate about. I have been so lucky, great teachers with time to explain and show and when I was studying there were so many courses to choose from (perhaps a golden age, something to remember with fondness and lament its’ passing). Much has been said about the demise of the full time courses, I will refrain from adding my perspective. I do, however, have strong feelings about bookbinding, book arts, book conservation, etc. For those of a delicate nature please skip the next three or four paragraphs.

I did teach in the public sector for a number of years, but I became disenfranchised with the politics, the constant barrage of paperwork from the office (created by the people in the office to justify their jobs) and lack of foresight, in that numbers (money) were the only things that mattered. To give you an insight to the upside-down world it is, I will describe my last teaching post or should I say the conditions I and the students had to suffer. We shared a room, in a WW2 wooden and concrete hut, with ceramics and tillers. The roof leaked, the heating only worked when hit with a hammer, the equipment was poor, I could go on, but I hope you get the picture. When it came to the registration at the end of each class the teaching staff had one PC between 15 with the waiting time often over one hour. On the one occasion that I had to go to the office, appointment being made, I walked through 3 code locked doors.

It was rather odd, as each door opened the old tiled floor became carpeted, the paint fresher and the plants real. The third code locked door had smoked glass, pictures of happy students and certificates of excellence decorated the walls, leather upholstered chairs around a coffee table with a CCTV camera completed the anti chamber to the office. I rang the bell and with my ear to the intercom waited. And waited, had I the wrong time? The wrong day? I heard laughing through the door and then the portal to the office opened with a well oiled and not often used swish. I had entered a new dimension. The office had air conditioning, ambient lighting, cushions and all manner of wondrous things including many computers. As I stood on the threshold thoughts cascaded through my mind, the first being ‘so this is where the student fees go.’ As this thought and others were crumpled up and thrown into the basket ball hoop-rubbish bin I completed my business and gave in my notice.

Though there are a lot of part time courses (one day a week) and evening classes there are still a hand-full of courses in the UK based in the major art universities and one or two courses that are affiliated to examination bodies. Some are good, excellent, professional and dedicated staff, facilities (dedicated to that subject only) that match the expectations of the students, good contact hours with 4 or 5 days in the studio/workshop/classroom and a reputation that was not made 20 odd years ago, but is always being refreshed by the graduating students. What is more important is the fact that every student realises that if she or he does not do the required work to the required standard they fail or are marked down or have to re-take.

However, it has been my experience over the last 15 years or so, that most of the output and standard of work produced from some of the major colleges and universities has dropped to an alarming low. I run a number of short courses and extended programmes from the beginner through to application for Licentiate of Designer Bookbinders and beyond. Every year I get increasing numbers of students from BA and MA book arts courses and the like coming to me for extra tuition in core subjects. By core I mean the basics like how to make a book! Most of the students are non EEC and therefore pay huge amounts of money for the privilege of being taught or not taught at these household names in art education. It is just not fair. The students either save or borrow money to study here in the UK on courses that online or in the booklets seem so good.

Many are shocked by the reality, contact hours are measured in minutes, students have to ‘hot bench’ with other courses and find that facilities are no longer available (I heard from one student that on one book arts course there was one finishing press between 15 students). Elements of the courses are dropped or any number of things that leave the student dissatisfied. Teaching is to the lowest common denominator, everyone passes.

The problem is that many students fail to complain. One can understand why. They can hardly return home, hoping to find a job or start work as a professional bookbinder, book artist or book conservator and say “Well that 2/3 year course was an absolute waste of time and money, I learnt nothing” They will go home and big the course up. The ironic thing is, the students that take extra tuition use the work made outside of the university course in their final show………… Does this ring any bells with anyone ?

Needless to say invitations to graduate shows dried up some time ago.

Education is about the future, notice I say the future and not now.

Now is passed, as I write what I write becomes history. The future, for me at least, is an exciting place. Of course we do not have definite ideas of what the future will bring or what our actions will bring about, but as a teacher I feel I have a responsibility to help others fulfill their potential for their futures. It all sounds very pompous and grandiose, perhaps it is, but at least I and others of a similar ilk are doing what we can to provide possible foundations for a possible number of futures.

Studio 5 was set up with the Atelier principle in mind. We have a maximum of four dedicated student spaces and with a finishing press for everyone. Studio members range from senior conservators, Licentiates, students and beginners. We all have the book as our common ethos. I do not want this to become an advert for Studio 5 so I will finish answering this question by saying that if you do come to Studio 5 to learn, do not expect a piece of paper to show people what you can do, show them your work.

You also teach, lecture and exhibit around the world. What sort of challenges do you face when working in new spaces and with other languages? Do you find that terminology is difficult to translate?

Simply, I love my job. I have met some fantastic people, been to some memorable places, eaten many foods and I hope I have been able to share some of what I do with others and that it is worthwhile for them.

Whether I teach/lecture in Studio 5 or in other locations, language or the understanding of language can be an issue. Perhaps it is not the students with English as their second or third language, the biggest complications or sticking points can be when English is the first language. Even more so when different words mean the same thing, for example section and signature. Each is correct and each is wrong. I believe that a good teacher has to be flexible in the delivery of a workshop. Working with students with impaired hearing is a point in case, the teaching strategy I use is to demonstrate, then explain, then repeat both the demonstration and the explanation (The student cannot watch both my mouth and the demonstration at the same time). I tend not to give out notes. The reasoning behind this is simple, the student is encouraged to make their own notes in their preferred language, illustrate or take pictures on the phone or camera.

In the early days of Studio 5 one problem I remember was when a very adamant person with a substantial number of years experience said that I had to teach her. I reluctantly agreed, however the student would not listen to instruction, watch demonstrations and asked the most bizarre questions at the most inappropriate times, suggested that she knew better ways of doing things. I kept thinking why was she here? Why did she want me to teach her? At lunch time we appraised the mornings work, she wondered why her work did not look as good as everyone else’s, saying that I had not been teaching her well enough. None of the other students had any problems and suddenly found the most interesting things to capture their attention on either the ceiling or the floor. I replied by saying that I could not teach her. With a rather smug smile she suggested that I was not a good enough and that her knowledge was greater than mine. I agreed and repeated that I could not teach her. I think it was then that one of the other students pointed out that what I meant was that I could not teach her because she did not want to learn. I do not waste my time and I do not waste students time. I asked her to leave. I think the only demonstration she followed was on how to open and close the studio door after her.

Education is a two way street, if the student is prepared to learn I am prepared to teach. I also have to be prepared to learn. I do not see challenges in teaching with no common language, a smile is a smile, a frown is a frown. Patience and a flexible approach works for me.

Studio 5 has all the kit, presses, benches, knives, board chopper, etc. Being in the UK also means that I have a number of suppliers for materials that can be the envy of many. It is also easy to become complacent, to expect all venues to have the same level as one is used to. I have been to seminars and the like where I have seen the wish list for some of the great and the good in bookbinding. Some are divas with no comparison. Work benches to be of a given height, a particular style of press and so on. I kid you not, I have witnessed one of the gods stamp his foot when the cutting mat supplied was not to his liking. How lucky he was to have any cutting mat in the first place.

Not all bookbinders have access to basic equipment, there has to be a make do approach to workshops and demonstrations. I have used rocks to press with, and other odds and ends to work with. I could go to places with a ‘mini’ Studio 5, but what purpose would it be for. I have to use what is available to my audience. To use the same papers, adhesives and knives. Often those who get the most out of workshops and demos are the ones that cannot afford to attend seminars and to be frank what is taught may be of little use. For me to buy a sheet of repair paper for £20 is ok and is factored in to the job costing. But imagine if the sheet of paper represented a month’s wages, the complexities are endless. To this end I try to go to places that have need of me and others. Not on the teachers map as it were. This is not easy as no funding is available because it is not fashionable so I self fund and the results are not quantifiable. As I said before, learning is a two way street. I often learn more than I teach, how to make with the least equipment and materials. How to see through problems until there are no problems only answers to as yet unasked questions.

Great interview, and great binding for Burgess’s Clockwork Orange. It captures the mayhem and creepiness of the book. I also loved the buried books. : }

Probably one of the best interviews I have read in a long time. So glad the challenges of the ‘art, profession and attaining these skills’ have been so honestly discussed! Also inspirational work!!!!

The Clockwork Orange piece by Mark is a personal favourite of mine, very creative! Great to see that he is the featured bookbinder of the month!