Tikilluarit was created for the An Inventory of Al-Mutanabbi Street exhibition, which began in 2012, exhibiting nationally and internationally until 2015. The exhibition showcases a collection of artist books and broadsides that are a response to the explosion of a car bomb in Al-Mutanabbi Street, the historic center of bookselling and arts culture in Baghdad, back in March 2007. The exhibit came to Cambridge and was exhibited in three parts. Unfortunately, the session I attended did not included this particular work (I wrote a post about it).

Tikilluarit is the collaborative work of three artists. But Roni Gross is the star of this post; her concept transformed a written piece into a conceptual binding. The sonnet, which makes up the text of the book, was recast from a Greenlandic series by Nancy Campbell titled “The Hunter Teaches Me To Speak” (originally published in Modern Poetry in Translation). The word ‘tikilluarit’ means ‘welcome’ in Kalaallisut, the native language in Greenland. The sonnet is as follows:

The hunter teaches me to speak

I place my fingers round his neck and feel

his gorge rise – or is he swallowing

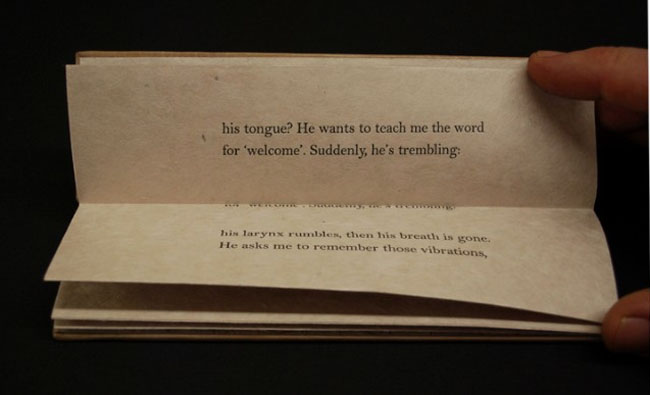

his tongue? He wants to teach me the word

for ‘welcome’. Suddenly, he’s trembling:

his larynx rumbles, then his breath is gone.

He asks me to remember those vibrations,

and, anxious as a nurse who takes a pulse,

touches my throat to judge its contortions.

Will I ever learn these soft uvulars?

I’m so eager, I forget that the stress

always falls on the second syllable.

My echo of his welcome is grotesque.

He laughs, an exorcism of guillemets,

dark flocks of sound I’ll never net, or say.

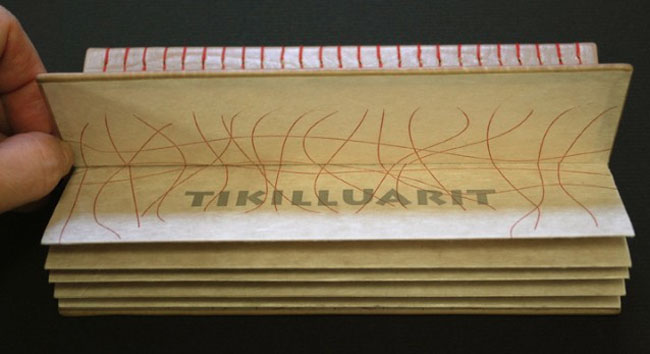

The modified accordion binding was executed by Biruta Auna using calfskin while Roni designed and letterpress printed the text on Mitsumata paper.

Tikilluarit is bound in such a way that offers little access to the interior parts of the book. How does the text and binding correlate to one another?

The poem speaks about a person trying to mimic the sound of a word spoken by another person by placing a hand around the throat of the speaker. The spine side of the book was made to be as visually important as the text block, which serves in effect, as the throat of the book. The text moves up and into the spine as if going down the throat. The exposed sewing is similar to the anatomy of the vocal cords.

The fourth collaborator is Peter Schell who crafted the unique sound sculpture that is paired with the deluxe edition of the book. In addition the deluxe edition includes a waxed linen wrap to house both the book and sound sculpture.

Paired with the book is a wooden sound sculpture that can be activated by shaking it. What does the element of sound bring to the experience of this piece?

The speaker in the poem says of the difficulty in learning to the language…”dark sounds that I will never net or say”. The wooden sculpture has an abstract wing pattern on the outside, which refers to an arctic bird which make a tinkling sound as its wings beat across the water. A sound that the human voice would not be able to replicate. It is another way of amplifying the words so that you can experience the poem in a physical way.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – –

I went into this interview not knowing very much about Roni, her history, her work or her artistic outlook. Through the interview, I hope you come to realize what I have: that Roni has a great appreciation for her artistic community and brings together unique artists in collaboration to expand on the concept of the book by conjuring up the senses. Enjoy the interview after the jump and sign up to receive email notifications so you don’t miss a post throughout the month of May which will feature more of Roni’s work.

I would love to start the interview with your origin story into book arts and printmaking. Did you discover one medium through the other?

I was a choreographer before I was involved in book arts, and one of the places that I took classes was in the same building as the Center for Book

Arts, when it was on Broadway above Houston. I used to go downstairs and look at the shows and was very heartened by the fact that whatever

you were interested in could be a book. I was working in a graphic design firm as a typographer and my boss had gone to the Philadelphia Museum

School of Art. He allowed me to do all kinds of personal projects using his space, and taught me how to make a book. Because he was an experimental

thinker, he encouraged me to explore different kinds of configurations in the book. At the end of the process I was pleased to have an object in my hand,

as opposed to a dance, which is ephemeral. I went on to take a letterpress intensive at the Center with Carol Sturm of Nadja Press. The sculptural quality

of letterpress was something that I was drawn to, and afterwards I began doing projects involving printing at The Center.

I am always intrigued by a person’s story for learning their trade. Did you have any formal training in either medium?

Over the years I have taken

classes with Susan Joy Share, Barbara Mauriello, Daniel Kelm, Keith Smith, Robert Bringhurst, Kitty Maryatt, Barbara Henry, Hedi Kyle and Emily

Martin. The exposure to lots of different kinds of bindings opened my mind to thinking of the configuration of the book in a more expansive way. Working next to Barbara Henry at CBA for a number of years, has definitely sharpened my eye to fine printing, and given me the patience to do more handsetting.

You’ve collaborated with poet Nancy Campbell and sculptor Peter Schell on a couple of artist books. What is the structure of your collaborative relationships and how do you find the work flourishes with their added talents?

We followed Nancy’s blog when she was in residence in Greenland several

winters ago, and the photographic images and descriptions of the land that she posted were very intriguing to us. She sent several poems that she had

written upon her return, and we immediately felt an affinity for them. Working with Peter Schell, who is a sculptor, I find that it extends the reach of the

book into a more physical realm. Sculpture is my favorite medium as it has a relationship to mass, and thus brings in my previous involvement with

the human body as a dancer. Nancy is able to pare down her language so that it feels like a direct transmission of experience. We communicate with her

regularly, sharing our ideas to see if she is in agreement with the direction we want to go. So far we have been in sync in a way that surprises all of us.

I think she is interested to see her work taken into another realm, and we are interested in making work that the viewer can experience in multiple ways,

rather than just being a visual experience. It is such a fruitful collaboration that we hope to do several more works together.

Z’roah Press held a table at the Fine Press Book Association Fair earlier in April. Do you often attend fairs and conferences to promote your work? Do you find that these events promote your work successfully?

We were pleased to have a table at the Fine Press Book Association fair in April, as it

gave us a chance to talk about our work to a wide range of people. You never know what may happen after the fair, so it is valuable to be present and have the work be seen. I have done Pyramid Atlantic years ago, and also the Oxford Book Fair in England. I am planning to have a table at The Manchester Book Fair this fall.

What’s the origin of Z’roah Press?

Z’roah is the hebrew work for shankbone. We chose that word for the work

that Peter and I do together because we feel that our work is elemental — down to the bone – if you will. The press began about 8 years ago when it became

clear that we wanted to do book projects together on a regular basis.

As an Artist Member at The Center for the Book in New York, can you first describe the benefits of the membership and then how it has impacted your work?

Artists Members can enter a work in the summer call to artists members that the Center has each year. We are also part of an online registry of images which is part of the website. Curators can refer to these images when planning a show or researching artists. There are also opportunities to have

work taken to a fair, to be part of CBA’s table to artists books. We are also starting an artist markeplace which will sell books by participating artist members.

You seem to be very involved with the Center, with your membership and also as a workshop instructor. How would you describe your relationship with the Center and its importance to the book community?

I am always looking to help the Center provide artists and students with services and good training.

I would like people to enjoy their time at CBA and deepen their involvement in bookmaking. The artists markeplace is a project that I initiated and I hope

it will provide artists with more visibility and the Center with some additional income.

Speaking of teaching, you’ve also taught at other venues such as Penland and the Women’s Studio Workshop. What types of workshops do you teach and who are your typical students? What aspects of teaching do you enjoy the most?

Penland is really heaven on earth. Everything runs so smoothly and all

the components make it a wonderful experience for everyone. I teach printing/printmaking on the vandercook – various traditional and nontraditional

techniques. Often I teach some structures so that people can begin including the physical object in their thinking as they are printing. Typical students range

from artists to hobbyists, and all ages.