Leafcasting is magic. Well, it at least LOOKS like magic. A not-oft-used conservation method, leafcasting helps to strengthen paper by filling areas of loss with pulp. Experimentation with this treatment began by hand in the 1950s, but was made considerably easier and more efficient with the advent of the leafcasting machine in the following decade.

There are only a small number of institutions that have leafcasting machines and an even smaller number that use them. At the Northeast Document Conservation Center, where I work as an assistant book conservator, we’re lucky enough to have one (on semi-permanent loan from the North Bennet Street School – thanks, Jeff!). Before coming to NEDCC, I had no idea what this machine was or what it did. Kiyoshi Imai, who has been with NEDCC’s book laboratory for over 20 years, is something of an expert on this treatment. He was kind enough to teach me the process (and re-train my brain on the intricacies of arithmetic) and I’ve been somewhat obsessed ever since.

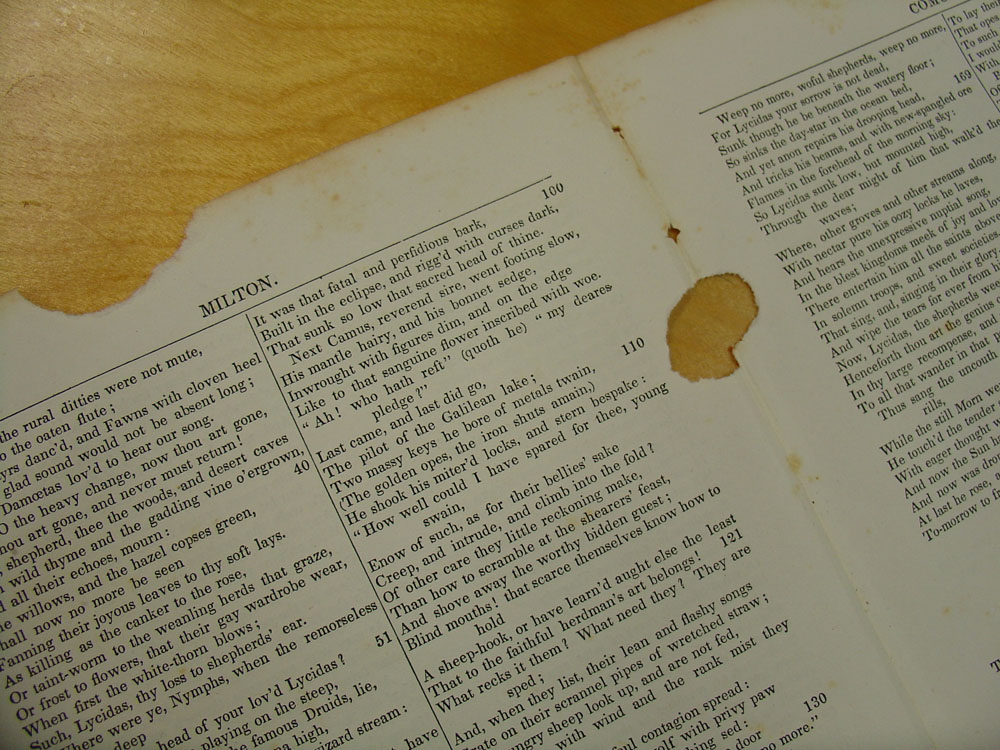

The leafcaster is essentially a paper-making machine. A document or folio (or multiple folios, as is sometimes the case) with losses is measured to determine the weight and full size dimensions. The areas with losses are measured and subtracted from that. There are a few more math steps in there, but essentially what you come up with is one number – this is the amount of pulp needed to fill the losses in grams. Leafcasting pulp can be made out of cotton and/or hemp fiber pulp or handmade paper. It is often necessary to use a combination of both, as one of the issues a conservator is attempting to address in the process is finding a good color match for the object.

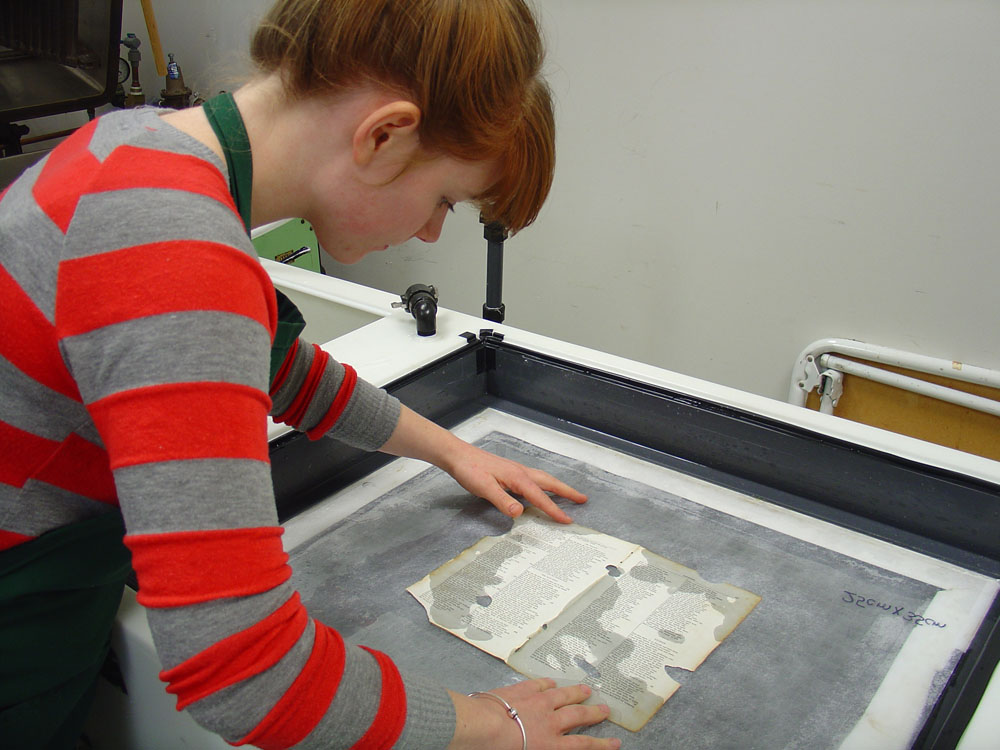

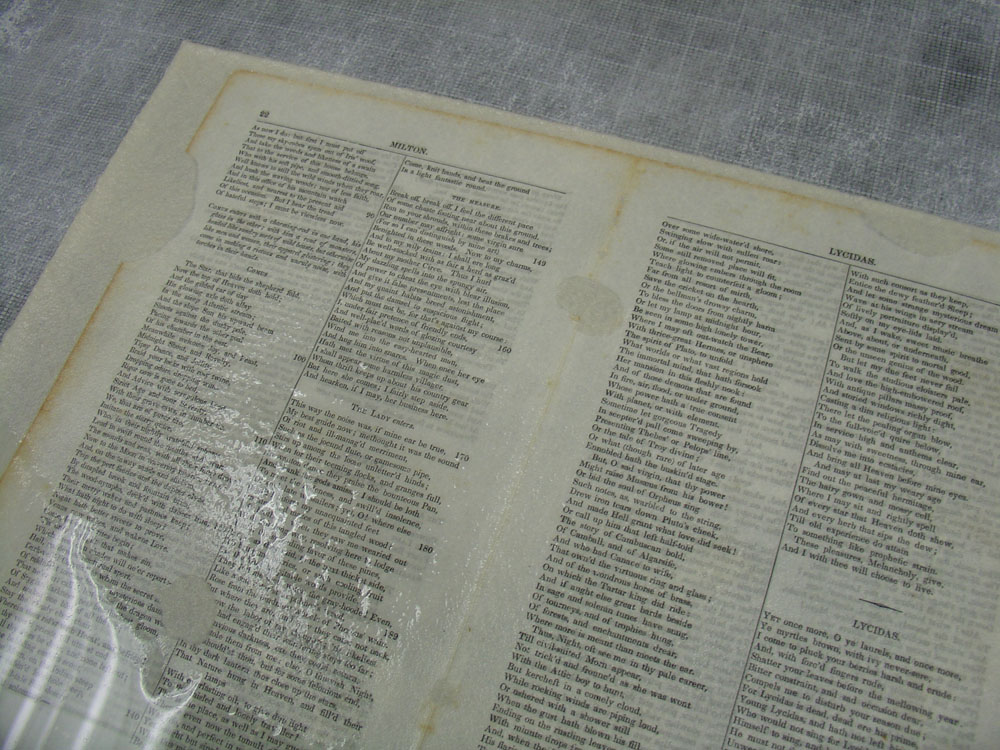

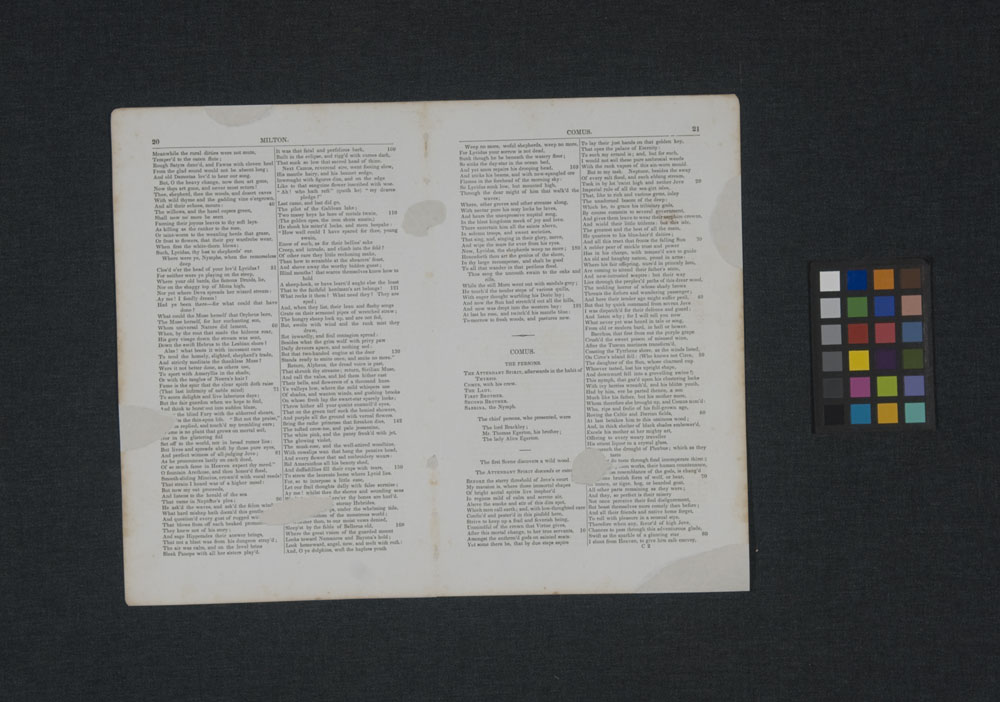

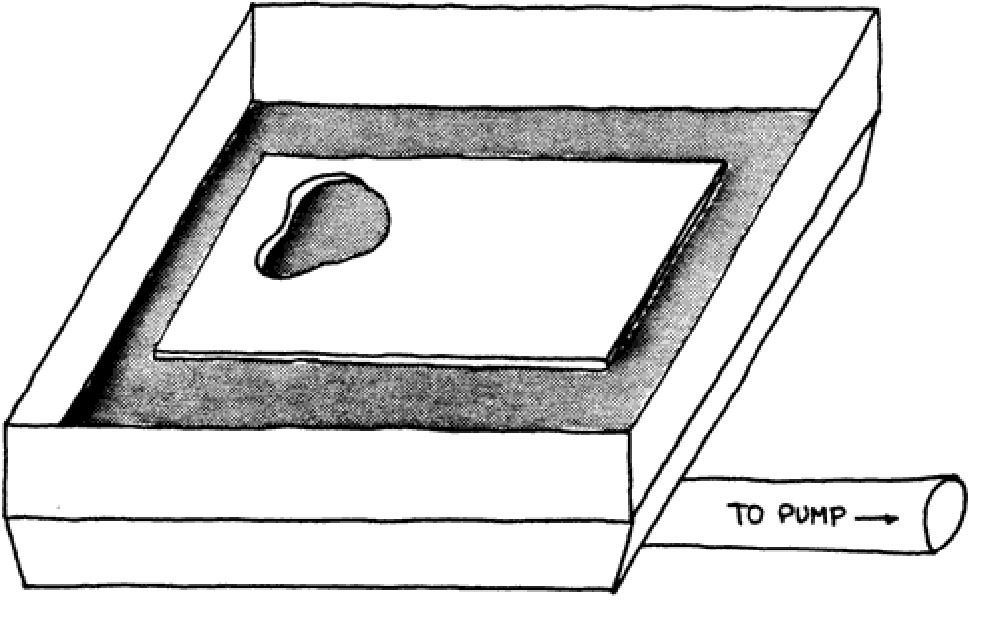

The material that is chosen is blended with water to form a slurry. The object is placed on a sheet of spun polyester (which makes for easier handling and allows water to pass through) in the “casting area” of the machine and is held down by a screen while water is poured in. The pulp slurry is added to this water, distributed evenly and finally removed from the casting area by a pump located below. The pulp is pulled to the areas in the object with losses. If the conservator has done their job well, the new material will appear even and well matched in thickness and color.

The cast object is removed from the leafcaster with a second sheet of spun polyester and can be sized on a suction table, which helps to improve the strength of the original object and the adherence of the new cast material to the original material. The object can be dried either in a press or under blankets, depending on the intended result – drying it in a press can often augment the size, so in the case of casting just a folio or two from a bound volume, it may be best to allow for a slower, more gentle form of drying. If the object is a one-off, it can be slightly faster to dry it in the press.

While it isn’t the appropriate treatment for all items, leafcasting can be a great option for some. Volumes that have large amounts of insect damage, for instance, often require a huge amount of mending time. Attempting to hand fill losses at that scale is daunting. Because the damage is usually fairly consistent, it is relatively easy to use the same math on large sets of folios. It’s also very likely that the same pulp would be used, so the biggest time commitment is just the initial set up. When an object is well cast, the strength and stability of it is greatly increased. Objects that have been cast are protected against further damage in weak areas and can be handled much more safely. Because it is essentially just handmade paper pasted to the object, it is also reversible.

It’s easy enough to create your own losses in sample materials, so if you’ve got access to a leafcaster, try it out!

I am currently working with Helen Bailey, Library Fellow for Digital Curation and Preservation at MIT, to develop software that can use digital images of objects with losses to determine the amount of pulp needed and will be leading a leafcasting demonstration and lecture for SUNY Buffalo’s art conservation graduate students this spring. I have also created a user’s manual for the Model 0901 Leafcaster, so if you have any related questions, please feel free to send them my way!